My father: Let’s go back to when I remember when we moved to 1109 Queen Street. When I was about six years old. And we had what they call a shotgun house. Three rooms. Front room, middle room, and a kitchen. And to get to the kitchen, you had to go out on the back porch and come through. Now there were some people who had a door cut in between the middle room and the kitchen, so you wouldn’t have to go out on the back porch. But they said if you cut that door somebody in your family would die. [Laughs.] So we wouldn’t cut the door. All of us slept in the middle room. See, we did have a bed in the front room later on, but first we slept in the middle room. And we had, like, what they called a day bed. You pull it out. And me, Lucian, and Jesse slept in that bed. And Hattie Margaret and Mama slept in the other bed. And then we had a laundry heater in the middle. We had to make fires every night. Go out –

Me: Laundry heater?

My father: Yeah, well, it was what you’d call a space heater. Laundry heater.

Me: Oh. Okay.

My father: — that you put, well, we used coal. Some people were afraid to use coal because it would get so hot it would turn red. And, you know, sparks would fly and sometimes things would catch on fire. And that’s what we used to heat the iron to iron clothes, too. You’d put ‘em on top of that stove. But we had to make fires every morning. Had to get up. And we had linoleum in there, so the floor’d be cold. So when you walk around you had to walk on your heels when – [we start laughing] – you get up out the bed and go out and get the wood. And then, you know, we had that little slop jar up under the big bed. You had get up to go — then, see, that house didn’t have a bathroom. So the bathroom was outside — the bathroom sat in between the two houses. And you had just a stool. And that stool had a big water tank on the top. And so when you lift the lid up, it would flush. So that was for 1109 and the one right beside it. Probably just had a little partition between. It was probably 1107, and that’s where the Davises, Miss Alliner [Alliner Sherrod Davis, daughter of Solomon and Josephine Artis Sherrod, and actually a cousin], she lived right there at 1107. And then we had the water outside, and it was at her house. So there were two houses that had one toilet and one spigot. So we would go out there and get the water and stuff like that.

Me: And so you said you remember moving in there?

My father: Yeah, we moved from off Elba Street. ‘Cause we moved at night. You know when your stuff a little shaky…. [Laughs.] Somebody come by, it’d be dark, with all your stuff on the truck. And I remember I had a little hat, and it blew off on Green Street [laughs], and I couldn’t stop to get my hat. ‘Cause it was dark when we moved. And that was when I was probably in the first grade. I think it was 1940 when we moved around there in all those little endway houses. C.C. Powell owned the houses, and I don’t know how much we were paying, but we weren’t paying a whole lot. Behind the outhouse, we had built up like a little shed, like. Used to keep pigeons in there. Everybody had pigeons. The ones that go off – we’d see in the movies the ones that take little messages and all. So everybody would have pigeons. And then we had a little, I guess it was a garden. We had a victory garden in the back. I had to take a hoe and a shovel and dig up the backyard. Turn it over. Then Mama would go out there and make some rows and plant tomatoes and stringbeans and squash and stuff like that, and we used that to eat. Now, when I was growing up, at that time, we didn’t have no money. I went to school, all the way through almost, some days I’d go and didn’t have a penny. Not one penny. In my pocket. Not one penny. … And the icebox, it was a little small icebox, and you’d take the ice and put it in the top, and then there was a little hole so when the ice’d melt, it would run down. You’d have to have a little water container underneath. You’d have to empty that everyday. If not, the water would run out on the floor, out on the back porch. And it would always be so clear and just cold, but we had to go to the ice house, and the ice house was out there on Herring Avenue. And I would ride the bicycle out there to get it.

This house was one of a row of six identical shotgun houses on Queen Street built circa 1925. I took this dim Polaroid image sometime in the very early 1980s, and they were torn down not long after.

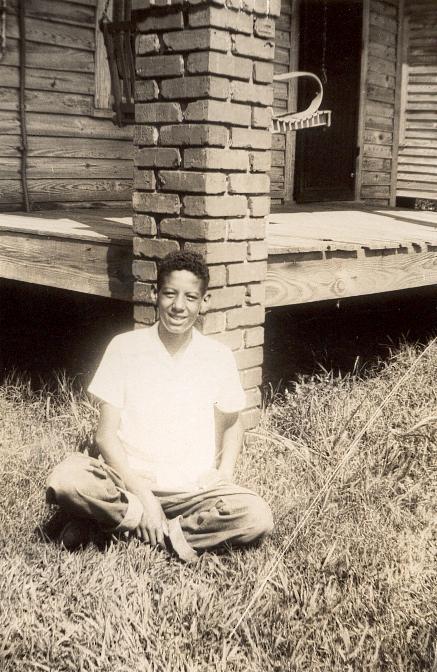

My father, age about 10, sitting outside a house on Queen Street. I’m guessing it’s 1107 because the door is on the opposite side of the house. Otherwise, the houses were identical.

——

Interview of R.C. Henderson by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved.