Remembering my grandmother’s beloved sister, Mamie Henderson Holt, on what would have been her 108th birthday.

Category Archives: Photographs

In memoriam: Louise Daniel Hutchinson.

Louise Daniel Hutchinson, scholar of black history, dies at 86

By Emily Langer, The Washington Post, 26 October 2014.

WASHINGTON — Louise Daniel Hutchinson, who gathered, documented and preserved African-American history during 13 years as director of research at the Smithsonian Institution’s Anacostia Community Museum in Southeast Washington, died Oct. 12 at her home in Washington. She was 86.

The cause was vascular dementia, said a daughter, Donna Marshall.

Mrs. Hutchinson spent much of her adult life working to collect and share with others the richness of African-American history in Washington and beyond. In 1974, after years of community activism, she joined the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, as it was then known. She retired in 1987.

Under the leadership of founding director John Kinard, she oversaw exhibits covering years of history in the Anacostia community, the movement of blacks from Africa to overseas colonies, and the life and accomplishments of Frederick Douglass, the former slave, abolitionist and distinguished writer.

She took particular interest in documenting the lives of African-American women such as Anna Cooper, who was born into slavery and became a noted educator and equal rights advocate. “Even black history hasn’t given black women their proper place,” Hutchinson once told the New York Times.

Gail Lowe, the Anacostia Community Museum’s senior historian, credited Mrs. Hutchinson with elevating the work of the research department and using individual life stories to illuminate broader history. “In telling the local stories,” Lowe said in an interview, “she validated community experiences.” Mrs. Hutchinson was “a stickler for accuracy and authenticity,” Lowe said, and insisted researchers keep magnifying glasses on hand for the close inspection of old photographs. Hutchinson, Lowe recalled, spotted Harriet Tubman and W.E.B. Du Bois in previously unidentified images.

“Because of the level and depth of her work,” Lowe said, “she was able to … provide accurate, documented information that other researchers and scholars relied on.”

Louise Hazel Daniel, one of nine children, was born June 3, 1928, in Ridge, Maryland, and raised in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington. Her parents, Victor Hugo Daniel and Constance E.H. Daniel, were teachers and friends of the African-American intellectuals and educators George Washington Carver and Mary McLeod Bethune.

After graduating in 1946 from the old Armstrong Technical High School in Washington, Mrs. Hutchinson attended colleges including Howard University and did secretarial work before beginning her career in historical preservation. In the 1970s, she assisted curators at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery with the selection of paintings featuring prominent African-Americans, her daughter said.

Mrs. Hutchinson’s writings included the books “The Anacostia Story, 1608-1930″ in 1977, “Out of Africa: From West African Kingdoms to Colonization” in 1979 and “Anna J. Cooper: A Voice from the South” in 1981.

Mrs. Hutchinson’s daughter Laura Hutchinson died in infancy, and her son Mark Hutchinson died in 1974, at age 8, of a brain tumor.

Survivors include her husband of 64 years, Ellsworth Hutchinson Jr. of Washington; five children, Ronald Hutchinson of Fort Washington, Maryland, David Hutchinson of Clifton Park, New York, Donna Marshall of Laurel, Maryland, Dana McCoy of Washington and Victoria Boston of Clinton, Maryland; two brothers, John Daniel of Washington and Robert Daniel of Atlanta; a sister, C. Dorothea Lawson of Bay City, Texas; five grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

In addition to her museum work, Mrs. Hutchinson participated in such initiatives as the development of D.C. public school curriculum in the 1980s, which incorporated the roles of black leaders in local events.

“I have real concerns about accuracy of history,” she told The Washington Post. “I believe it must reflect [the] participation of all.”

——

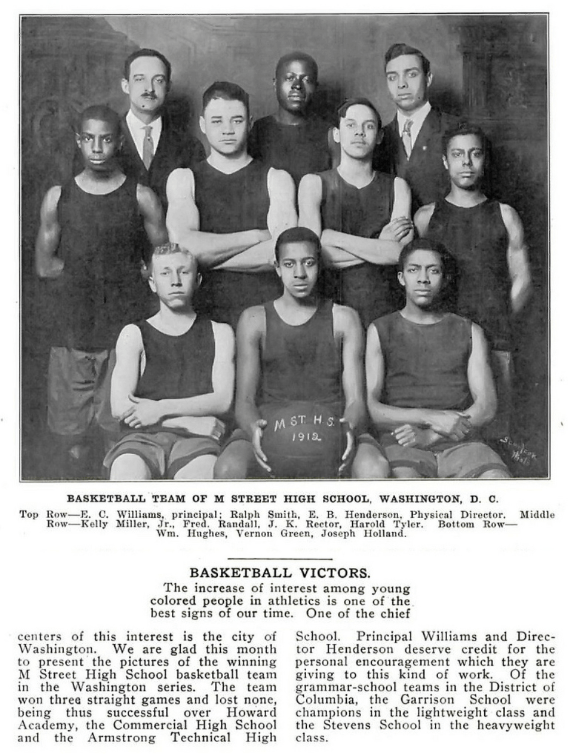

Basketball victors.

Many thanks to Dena Banks for pointing out this post in Vieilles Annonces’ Flickr feed. It’s from the March 1912 issue of the NAACP’s The Crisis. (The first 25 years of which I have on CD; I need to study this thing more carefully.) Fred Randall was the 17 year-old son of George and Fannie Aldridge Randall, who migrated from Wayne County to Washington DC in the late 1890s. (Fannie Aldridge Randall, formerly known as Frances Aldridge Locust, was the sister of my great-great-grandfather John W. Aldridge.) Randall’s interest in athletics did not end in high school. As just posted here, he went on to become director of the city’s Cardozo Playground.

Leaves post.

Jet magazine, 28 September 1961.

Jet magazine was founded in 1951. In 1955, its graphic coverage of Emmett Till’s murder catapulted its readership, and the magazine became known for chronicling the Civil Rights Movement. All this came swaddled in heavy layers of Negro firsts, Negro Hollywood, and general Negro bougie news. I’m sure my grandmother was reading Jet — and probably subscribing to it — by 1961. What did she think when she saw her father, whom she only met once, lauded in its pages?

Nuptials discovered. (And a little Misinformation Monday, no. 11.)

My grandmother’s birthday was Saturday, June 6. It would have been her 105th. My cousin D.D., her sister’s great-granddaughter, sent me a photo of a photo via text message — Mother Dear and her husband, Jonah Ricks, my step-grandfather. I’d never seen this particular image, but I recognized it as having been taken in Greensboro, North Carolina, at her niece L.’s wedding in 1963.

… Or was it?

I found their marriage license today. So, first, I had to pick my jaw up. I knew they’d wed in August 1958, but had never been able to find a record in Wilson. Because they married in Guilford County. In Greensboro. I immediately thought about this little snapshot. This wasn’t taken in 1963! Mother Dear and Granddaddy Ricks had traveled to her sister’s for the ceremony, and this photo was taken on their wedding day. Why hadn’t I registered the boutonniere, the corsage, the beringed left hand held high?

Then I got around to looking at the rest of the license.

First, there’s the matter of my grandmother’s name. In that era, legal names were somewhat fluid, and changing them did not necessarily involve legal drama. Bessie Henderson bore my grandmother before North Carolina required birth certificates. Bessie named the baby Hattie Mae and gave her her last name. Bessie died less than a year later, and little Hattie went to live with her great-aunt and Uncle, Sarah and Jesse Jacobs. She called them Mama and Papa and became known as Hattie Jacobs. Only after Sarah’s death in 1938 did my grandmother learn that she had never been formally adopted. (And as a consequence, she was forced out of the house on Elba Street by Jesse Jacobs’ children.) She immediately changed her name to Hattie Mae Henderson. I was surprised then to see her name listed as “Hattie Jacobs Henderson” some 20 years after she dropped the appellation.

Mother Dear also listed Jesse and Sarah Jacobs as her parents on the license. Here is an example of the way documents may reflect social and familial realities, rather than legal or genetic ones. Curiously, though, there is a hint to Mother Dear’s paternity in the license, though inexplicably placed. Mama Sarah was born Sarah Daisy Henderson. Her first husband was Jesse Jacobs and her second Joseph Silver. She was not an Aldridge. But my grandmother’s birth father was. Why did my grandmother report Sarah’s name this way? Maybe Mr. Ricks gave the information and got his facts twisted?

Last, the witnesses. I recognize James Beasley — he married my cousin Doris Holt — but who were the others? Friends of my great-aunt Mamie Henderson Holt, perhaps?

What was.

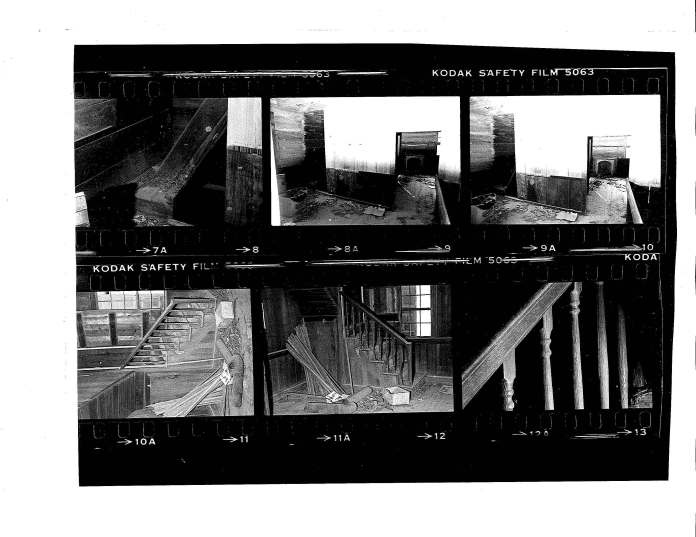

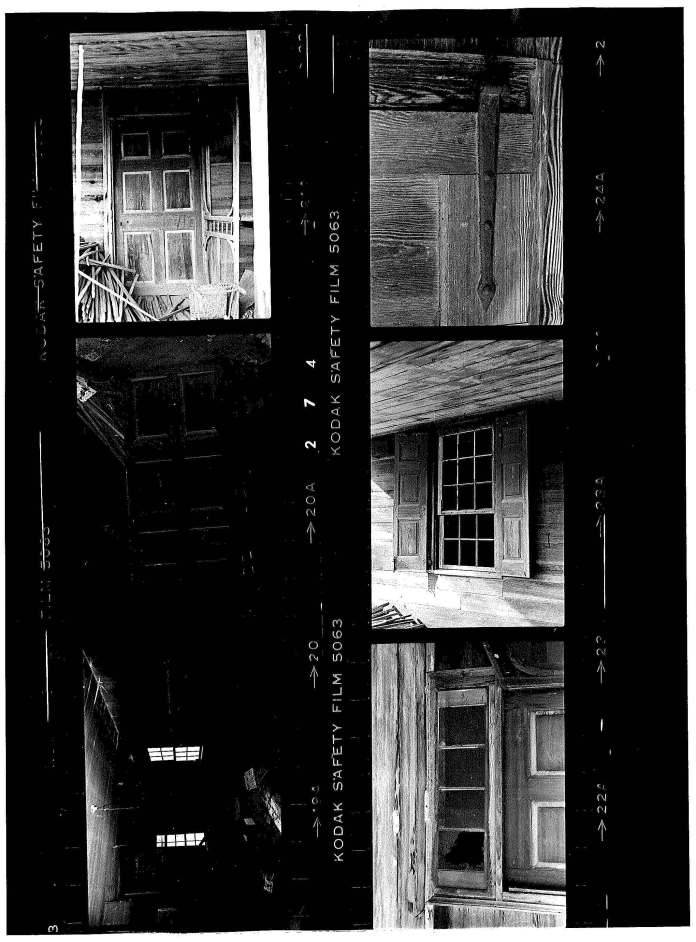

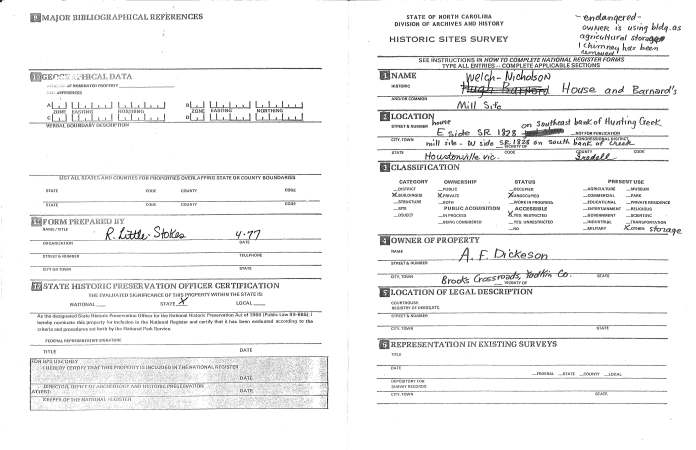

Photographs from the Welch-Nicholson House and Mill Site National Register nomination file held at the North Carolina Historic Preservation Office, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Raleigh. Many thanks to File Room Manager Chandrea Burch and National Register Coordinator Ann Swallow.

My great-great-grandmother Harriet Nicholson Tomlin Hart walked these rooms.

This, of course, is all gone now. Burned to the ground one night in the 1980s.

The Man.

When I was in North Carolina for my mother’s birthday, we had a great visit in Greene County with my new Sauls cousins. Before leaving, I made a copy of a photo of Isaac Sauls Jr., cousin Andrew’s father — carpenter, mill owner, farmer and all-around shrewd businessman.

Photo courtesy of Andrew Sauls.

“Well, she was pretty.”

And Mama’s daughter’s name Hattie, Hattie Mae. That’s who they named me after. I asked them why they named me Hattie after a dead person. “What, you don’t like Hattie? Well, I just thought ’twas nice.” And after I looked at the picture, I said, “Well, she was pretty.” Well, since Jack knew her, and he wanted her picture, so when I come up here, I give him the picture. And he kept it. They thought she was white, wanted to know what old white girl was that. And the frame was out on, right on whatchacallem street now where Mildred live, it was out there on her back porch, and I saw the frame, and I asked something about the picture, what happened to the picture, and she said she didn’t know what happened to it, it was some of Daddy’s stuff he brought here. I said, “Well, I know ’cause I gave him the picture, that frame where was sitting right out on the back porch.” He wanted it, and it was Bessie — not Bessie, but Hattie, Mama’s daughter Hattie. I said, “’Cause they grew up together.” “I don’t know who that old white girl was. I don’t know what happened, … he brought the stuff when he got sick, you know. Waited on him, you know… And he died, so…” Never did find out what ever come of the picture. They thought ’twas a white woman.

Mama never talked about her. But A’nt Nina, she would tell everything. Mama got mad with her, said, “You always bringing up something. You don’t know what you talking ’bout.” So she’d go behind — Mama wouldn’t want her to tell things. And she never did say, well, if she said, I wouldn’t have known him, but I never did ask her who Hattie’s daddy was. I figured he was white. Because she looked — her hair and features, you know, white.

It’s hard to see, but here lies the first Hattie Mae. Born just seven months before their marriage, Jesse Jacobs Jr. adopted Sarah Henderson‘s daughter as his own. (I need to clean this stone next time I’m in Dudley. I’m ashamed I left it like this this time.)

Interview of Hattie Henderson Ricks by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved.

Aunt Golar makes fashion history.

I’m not sure how it is that I didn’t write this months ago. When I went home for Christmas, there was a manila envelope on my dresser, postmarked U.K. I was puzzled. Who would be sending something from England to my parents’ house? I ripped it open, and a slender paperback slid into my hand, a scholarly journal — Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, volume 2, number 1.

I scanned the contents and suddenly remembered. Some years ago, I contributed photographs of my people to Min-Ha T. Pham’s Tumblr, Of Another Fashion. In the journal article, “Archival intimacies: Participatory media and the fashion histories of US women of colour,” Pham discusses “the critical and curatorial aims, materials and methods that underpin a digital fashion archive devoted to the histories of US women of colour ….” arguing for “the utility of participatory media in efforts to create not only new historical records of minoritized fashion histories but also new systems of record-keeping.” Among the photos illustrating the piece is one of my grandmother’s aunt, Golar Colvert Bradshaw.

Family cemeteries, no. 16: Holmes-Clark.

No one knows where Joseph R. Holmes is buried. It stands to reason, though, that it might be here.

I owe this entire post to the inestimable Kathy Liston, a Charlotte County archaeologist who has immersed herself in the history of the area’s African-American families. She tracked down the location of Joseph’s small acreage near Antioch Church on Old Kings Highway near Keysville, Charlotte County,Virginia. And there, at edge of a clearing, now completely overgrown, is a small cemetery. Only four stones stand, but a number of unmarked or fieldstone-marked graves are visible:

Rev. Whitfield Clarke / Born July 15, 1840 / Died Aug. 21, 1916

In Memory of Our Beloved Son / Thomas C.C. Clark/ Born Sept 2, 1882 / Died Aug 27, 1907

William Jasper Almond / Virginia / Mess Attendant / 3 Class / USNRF / A[illegible] 2, 1934

Mary J. Barrett / May 16, 1903 / May 2, 1942 / Her Memory is Blessed

These folks are not Joseph’s family, per se. They are his wife’s and are evidence of the life she built after his assassination.

Joseph Holmes married Mary Clark toward the end of the Civil War. Their four children were Payton (1865), Louisa (1866), William (1867) and Joseph (1868). Mary was the daughter of Simon and Jina Clark, and Whitfield Clark was her brother. As detailed here, Joseph R. Holmes was shot down in front of the Charlotte County Courthouse on 3 May 1869.

When the censustaker arrived the following spring, Joseph and Mary’s children were listed in the household of a couple I believe to have been Joseph’s mother and stepfather: Wat Carter, 70, wife Nancy, 70, and children Mary, 23, Liza, 17, and Wat, 16; plus Payton, 4, Louisa, 3, and Joseph Homes, 2, and Fannie Clark, 60. (That Mary is possibly Mary Clark Holmes, but may also have been Mary Carter.)

On 3 January 1872, 24 year-old widow Mary Holmes married John Almond, a 35 year-old widower. In the 1880 census of Walton, Charlotte County, carpenter John Almond’s household includes wife Mary, 31, and children Payton, 14, Wirt H., 12, Ella M., 10, and Lemon Almond, 8. Payton, it appears, was in fact Joseph’s son Payton Holmes; Wirt and Ella were John’s children by his first wife; and Lemon was John and Mary’s son together. The family remained on the land that had been Joseph Holmes’.

The oldest marked grave in the little cemetery dates to 1907. It stands to reason, though, that Mary Holmes would have had her husband buried here, where she could watch over his grave and perhaps protect it from any who sought to punish him further. Who were the four whose stones still reveal their resting places? Thomas C.C. Clark was the son of Whitfield Clark and his second wife, Amanda. He appears in the 1900 census as a student at Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia. I’ve written a bit about Reverend Whitfield Clark here. William Jasper Almond (known as Jasper, which is interesting because that was the name of Joseph Holmes’ brother, my great-great-grandfather), born in 1896, was the son of Lemon Almond and his first wife, Rosa W. Fowlkes. Mary J. Almond Barrett was Jasper’s half-sister, daughter of Lemon and Mary B. Scott Almond.

Joseph R. Holmes’ land, near Keysville, Charlotte County, Virginia.

Photos by Lisa Y. Henderson, July 2012.