In case you’re interested, here’s the text of the Supreme Court’s decision regarding Bertha Hart Murdock’s land. Property law is not my strong suit, especially as it applies to inheritance, so I will not attempt an explication.

——

This is an action for a declaratory judgment construing the last will and testament of T. L. Hart, deceased, and adjudging that by virtue of said last will and testament the feme plaintiff is the owner of an indefeasible estate in fee simple in certain lands described in the complaint, and has the power, with the joinder of her husband, to convey the same in accordance with her contract with the defendant.

The facts admitted in the pleadings are as follows:

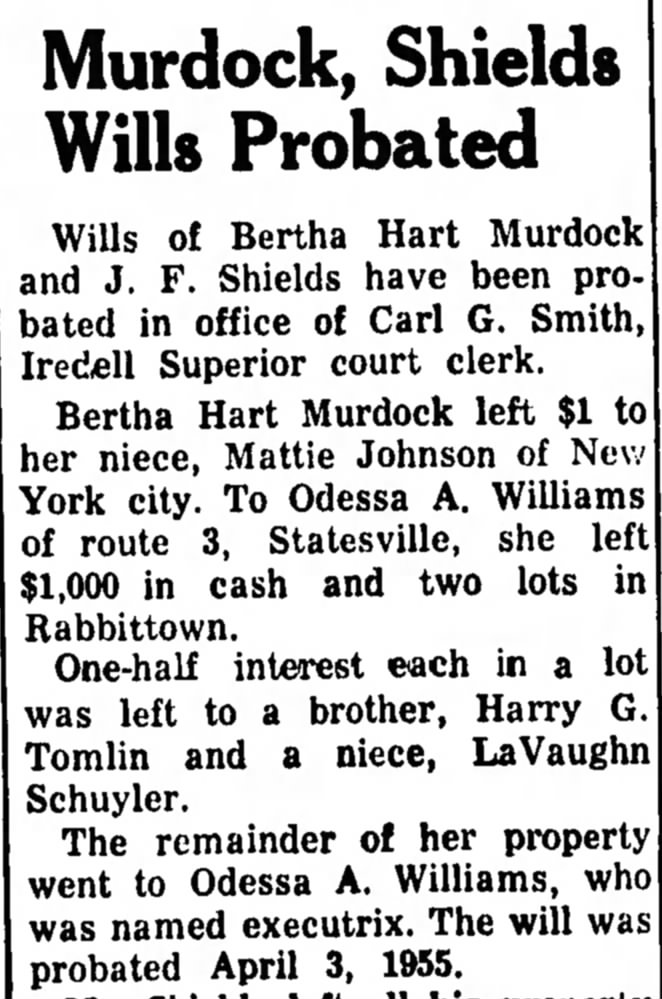

T. L. Hart died in Iredell county, N. C., during the year 1930, having first made and published his last will and testament, which was duly probated by the clerk of the superior court of Iredell county, and recorded in the office of said clerk on June 4, 1930.

By his last will and testament, the said T. L. Hart devised his home place in Iredell county “to my daughter, Bertha May Hart and her bodily heirs, forever, never to be sold, and if she dies without bodily heirs, then it must be in trust for my sisters’ heirs, to hold but never to sell the same.”

By a codicil to his said last will and testament, the said T. L. Hart devised to his daughter, Bertha Mae Hart, a tract of land in Iredell county, containing forty-five acres, and described in the complaint by metes and bounds.

At his death, T. L. Hart left surviving as his only heir at law his daughter, Bertha Mae Hart, who has since intermarried with the plaintiff W. J. Murdock. He also left surviving five sisters, three of whom are married. Each of these sisters has children. Neither of his two unmarried sisters has children. Both are now over fifty years of age.

On April 1, 1935, the plaintiffs and the defendant entered into a contract in writing, by which the plaintiffs agreed to convey to the defendant a fee-simple estate, free and clear of all liens or incumbrances, in two tracts of land, one tract containing twelve acres, and being a part of the home place of T. L. Hart, deceased, which was devised to the feme plaintiff by the said T. L. Hart in his last will and testament, and the other tract containing forty-five acres and being the tract which was devised to the feme plaintiff by T. L. Hart, deceased, by the codicil to his last will and testament. By said contract, the defendant agreed to pay to the plaintiffs the sum of $1,000, upon the execution and delivery to him by the plaintiffs of a deed conveying both said tracts of land to the defendant, in fee simple, in accordance with said contract.

The defendant has refused to accept the deed tendered to him by the plaintiffs, and has declined to pay the plaintiffs the sum of $1,000, in accordance with said contract, on the ground that the feme plaintiff is not the owner of an indefeasible estate in fee simple in said tracts of land, and for that reason the plaintiffs cannot convey to him such an estate in said lands, in accordance with their contract.

On these facts the court was of opinion and so held that the feme plaintiff is the owner of an indefeasible estate in fee simple in the forty-five-acre tract, but that she is not the owner of such an estate in the twelve-acre tract.

It was accordingly ordered, considered, and adjudged that plaintiffs are not entitled to the specific performance by the defendant of the contract set up in the complaint, and that the defendant recover of the plaintiffs the costs of the action. The plaintiffs appealed to the Supreme Court, assigning as error the holding of the court that the feme plaintiff is not the owner of an indefeasible estate in fee simple in the twelve-acre tract described in the complaint.

Opinion

CONNOR, Justice.

There is no error in the judgment in this action. By virtue of the last will and testament of her father, T. L. Hart, deceased, and under the statute, C. S. § 1734, the feme plaintiff is the owner of an estate in fee simple in the twelve-acre tract described in the complaint. This estate, however, is defeasible upon the death of the feme plaintiff without bodily heirs. Whitfield v. Garris, 131 N. C. 148, 42 S. E. 568, and Id., 134 N. C. 24, 45 S. E. 904. It is clear that the words “bodily heirs,” used by the testator, must be construed as meaning children or issue; otherwise the limitation over to the heirs of the sisters of the testator would be meaningless. Rollins v. Keel, 115 N. C. 68, 20 S. E. 209. See Pugh v. Allen, 179 N. C. 307, 102 S. E. 394.

The limitation over to the heirs of the sisters of the testator, upon the death of the feme plaintiff, without bodily heirs or issue, is not void. The provision in the will that the home place of the testator, which includes the twelve-acre tract described in the complaint, shall not be sold by either the feme plaintiff or the remaindermen is void as against public policy. This provision, however, does not affect the validity of the devise either to the plaintiff or to the remaindermen. See Lee v. Oates, 171 N. C. 717, 88 S. E. 889, Ann. Cas. 1917A, 514.

There is nothing in the codicil which affects the estate in the home place of the testator devised in the will to the feme plaintiff.

The judgment is affirmed.