Me: Okay, and Emma, she was up in Bayonne.

My grandmother: This man went up there in his young years. I think he had an eye on her. People used to say that the men — all of Mama and her sisters were supposed to have been catches, you know. They were good-looking women and everything, and they just said the men said it didn’t matter which one it was so long as they got one of them.

Me: One of the McNeely girls?

My grandmother: McNeelys. Mm-hmm.

Me: So he came back and married Aunt Emma and carried her to New Jersey. To Bayonne — oh! Irving Houser, Sr.

——

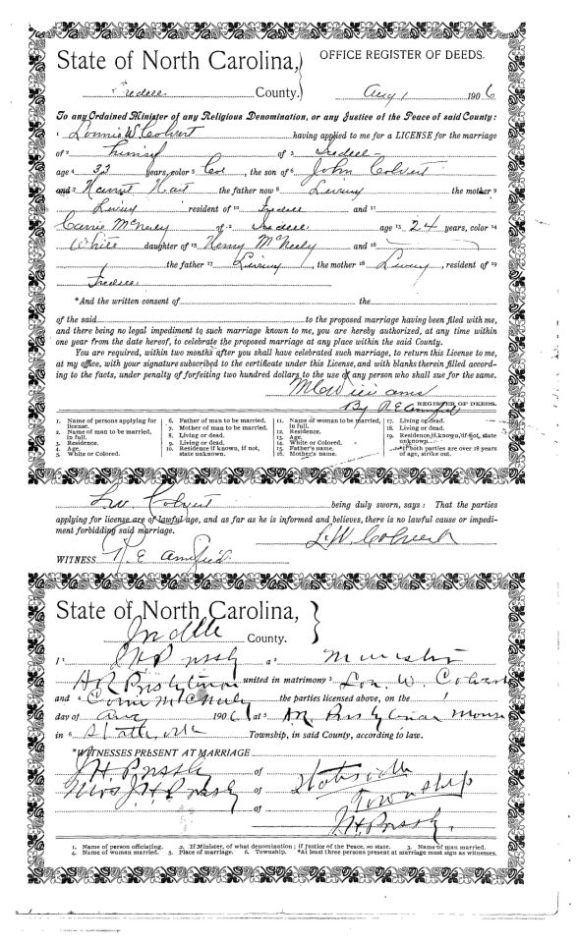

Irving L. Houser was born in 1885 in Iredell County to Alexander “Dan” and Lucy Houser. He and Emma McNeely were married 6 September 1910 in Statesville. The couple migrated to Bayonne, New Jersey, and settled on Andrew Street.

Six years later, in a span of three days, Irving appeared twice in New York City newspapers. First:

OLD JOBS OFFERED BAYONNE STRIKERS

Standard Oil Co. Tells Them They May Come Back, But Without Increase of Wages.

MRS. CRAM PLANS NEW VISIT.

Says She Will Consult a Lawyer and Won’t Be Barred — Federal Conciliators at Work.

The Standard Oil Company refused yesterday to grant the wage increases demanded by employees whose strike has tied up practically every big Plant in the Constable Hook section of Bayonne, N.J. for more than a week, but offered to take the strikers back at the old wage scale whenever the men wanted to resume work. The Committee of Ten, which learned these terms from George B. Hennessey, General Superintendent of the Bayonne plant, endeavored to report to the body of strikers. The police prevented them because no police permit to hold a mass meeting had been requested, but one was issued for a meeting this morning, at which the strikers will decide whether to accept or decline the terms.

…

Pending today’s meeting, the strikers were quiet yesterday. Early in the morning there had been some disorder at Avenue E and Twenty-fourth Street, bringing a squad of policemen, who fired as many more. They caught Irving Houser of 92 Andrew Street, an employee of the Edible Products Company, which plant is near the Tidewater Oil Company, and locked him when they found a revolver in his pocket.

New York Times, 18 Oct 1916.

Then,

Bayonne, N.J.

Miss Viola Houser, of Orange, N.J., visited her brother and sister, Mr. and Mrs. Irving Houser, Andrew Street, on Sunday, October 10.

New York Age, 21 Oct 1916.

Amid social unrest and social calls, Irving and Emma had three children: Mildred Wardenur (1913), Henry A. (1915) and Irving L. Houser Jr. (1920). For many years, Irving worked in various jobs in an oil refinery, but by time he registered for the “Old Man’s Draft” of 1942, he was employed at Bayonne City Hall. By then, he had purchased a house at 421 Avenue C, a site now occupied by Bayonne Giant Laundromat. Irving Houser Sr. died in 1962.

My grandmother wasn’t sure, but knew it wasn’t her mother Carrie, or Aunt Emma, or Aunts Minnie or Janie. Nor, she thought, was it Aunt Lizzie or Aunt Elethea. Which leaves Addie, but she nixed her, too. Not to second-guess my grandmother — or, well, to second-guess her, but in the most respectful way — I’d put my money on Addie, who died when my grandmother was about 9 years old.

My grandmother wasn’t sure, but knew it wasn’t her mother Carrie, or Aunt Emma, or Aunts Minnie or Janie. Nor, she thought, was it Aunt Lizzie or Aunt Elethea. Which leaves Addie, but she nixed her, too. Not to second-guess my grandmother — or, well, to second-guess her, but in the most respectful way — I’d put my money on Addie, who died when my grandmother was about 9 years old.