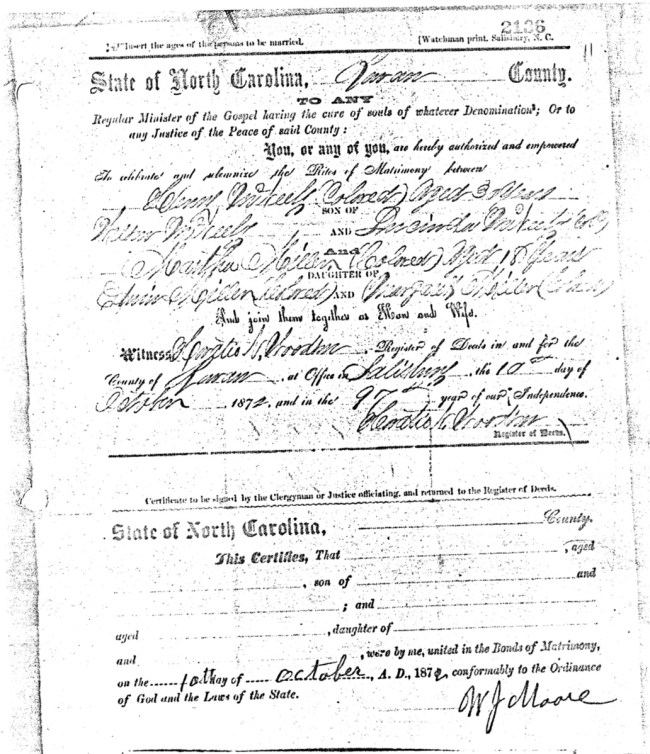

My grandmother said he looked a bit like a poet. Or so she was told:

See, I never did know Grandpa Henry. I didn’t know him. He died just as Louise was born. Mama had just had Louise, and it was real hot and all, and they told her she couldn’t go to the funeral because it was so warm and she would take cold. But I didn’t know him.

And:

Mama said he looked just like Walt Whitman. You know, he was, his father was white. I don’t know who his mother was. I don’t know if she was mulatto or what. But anyway, he was really light. And he lived on the same farm as his daddy. And he provided him, he provided for him as if he was his own child.

White child, that is.

[Sidenote: “Louise” was Mary Louise Colvert Renwick, my grandmother’s sister, born in 1906. — LYH]

——

Interview of Margaret C. Allen by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved.