My grandmother’s favorite cousin was her Aunt Lethea’s son, “Jay” or “J.T.”:

My grandmother: I had a cousin named Jay. Aunt Lethea’s son. She died and left three sons. James –

Me: Charles.

My grandmother: Charles. And Jay.

Me: Okay. J.T.

My grandmother: Mm-hmm. And Jay stayed with Aunt Min ‘cause Aunt Min reared him after Aunt Lethea died. And he was at this same house with Aunt Minnie and Grandma. Let’s see. It was Aunt Min and Grandma and Uncle Luther and Jay and I. We were all in the same house during the summer that I worked up there. And Jay and I used to have a good time. Oh, he was so nice. He would, the first time I rode on a rollercoaster, he took me. And we used to have a good time. He was really nice. He was a nice person.

Jay had two brothers, William and Charles. In the 1910 census of Statesville, Iredell County, I found three boys, William, 5, James, 3, and Charlie McNeeley, 2, living in the household of Sam and Mary Steelman and described as their grandsons. I identified these children, correctly I believe, as Elethea McNeely‘s children. I also guessed that Charlie Steelman, listed in the household, was their father. If he was, he and Lethea never married. Instead, in 1920, she wed Archie Weaver, a man my grandmother spoke of with vitriol.

My grandmother: Jay’s daddy had TB, and he just gave it to them. And his mother and Jay. But he lived years and years and years after both of them died.

Me: The father did?

My grandmother: [Inaudible] give them all this stuff. Oh, I could not stand him. She was my special aunt because she had boys, and she didn’t have any girls. And she just took me over her house, you know, and let me do things that girls did, you know.

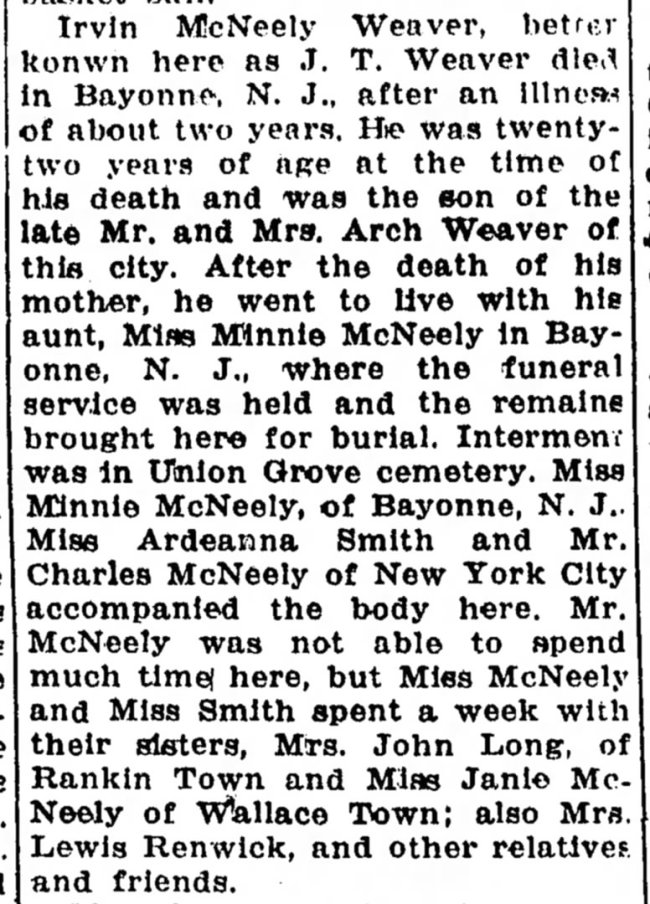

I was unable to find James McNeely, whom I believed to be “Jay,” in any other record. I knew Jay was reared by his aunt, Minnie McNeely, and died young of the same dread illness that killed his mother, but I was never able to find a trace of him. That changed last night, when I stumbled upon his death announcement in the 15 December 1933 issue of the Statesville Record & Landmark:

As Grandma Carrie so memorably said, “Well, I’ll be damn.” Here was J.T., as last. Not James McNeely — much younger, in fact — but Irvin McNeely Weaver. (The same “mysterious” Irving McNeely listed in the 1930 census in Martha McNeely‘s Bayonne household. He was described as her nephew, rather than her grandson, and I jotted in my notes: “Who is this???”) My grandmother was married and living in Newport News, Virginia, at the time of his death, and is not among his named survivors. Ardeanur Smith was his cousin, not his aunt, and Charles McNeely was his brother. Mrs. John Long was his aunt Lizzie McNeely Long, and Mrs. Lewis Renwick was his cousin Louise Colvert Renwick.

The first photo is Jay as a boy, perhaps around the time he moved to Bayonne. The second, taken in Bayonne circa 1928, shows Jay with his first cousins Ardeanur Smith, Margaret Colvert and Wardenur Houser, and an unknown girl seated in front. The last is Jay, alone, perhaps not long before he died.

——

This is just one of many, many times that I’ve found something that one or the other of my grandmothers would have been “tickled” to see. They both lived good, long lives — to 90 and 101 — but I would have kept them with me always if I could.

Interview of Margaret C. Allen by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved. Photos in the collection of Lisa Y. Henderson.