The hospital was on East Green Street, right around the corner from Jackson Chapel and Saint John AMEZ and Calvary Presbyterian. That last Sunday in June, two days after her first delivery, my mother lay perspiring in an iron bed, smiling uncomfortably as she accepted congratulations from church ladies making their post-service rounds. (The first reports went out: the Hendersons had a jowly yellow girl with a slick cap of black hair, a “Chink” baby, as one later indelicately put it.) She was desperate to be discharged, but had to wait for an all-clear from the pediatrician. It was not as if he were right down the ward. Dr. Pope was white, and as his black patients were forbidden to come to him, making his rounds meant driving across the tracks to them, laid up in sweltering Mercy Hospital. He arrived Sunday evening, turned me this way and that, pronounced himself satisfied, and granted us a release for the next morning. A few months later, when federal law mandated that Wilson’s new hospital open as an integrated facility, Mercy closed.

The hospital was on East Green Street, right around the corner from Jackson Chapel and Saint John AMEZ and Calvary Presbyterian. That last Sunday in June, two days after her first delivery, my mother lay perspiring in an iron bed, smiling uncomfortably as she accepted congratulations from church ladies making their post-service rounds. (The first reports went out: the Hendersons had a jowly yellow girl with a slick cap of black hair, a “Chink” baby, as one later indelicately put it.) She was desperate to be discharged, but had to wait for an all-clear from the pediatrician. It was not as if he were right down the ward. Dr. Pope was white, and as his black patients were forbidden to come to him, making his rounds meant driving across the tracks to them, laid up in sweltering Mercy Hospital. He arrived Sunday evening, turned me this way and that, pronounced himself satisfied, and granted us a release for the next morning. A few months later, when federal law mandated that Wilson’s new hospital open as an integrated facility, Mercy closed.

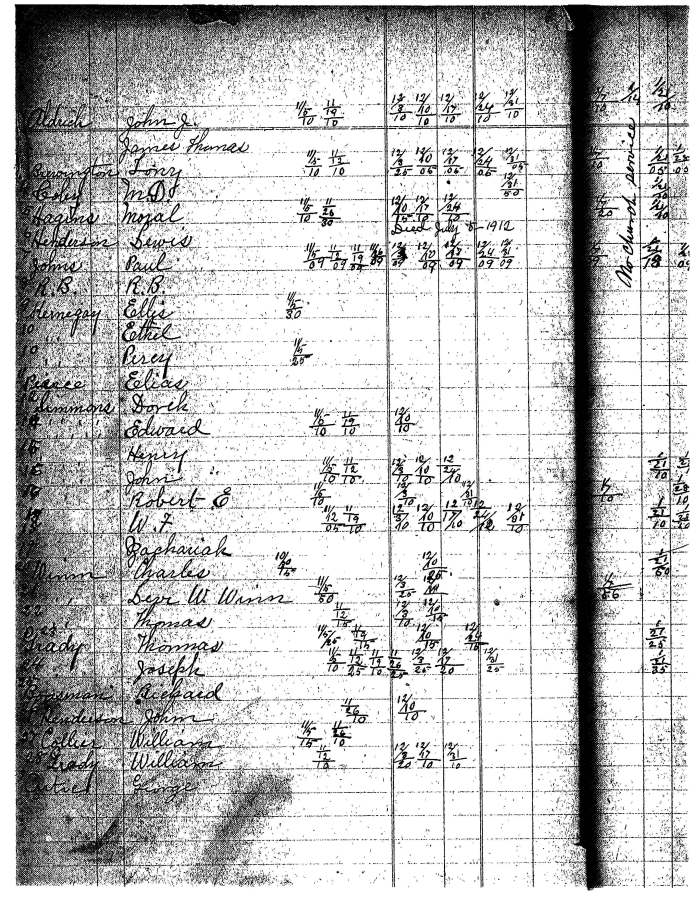

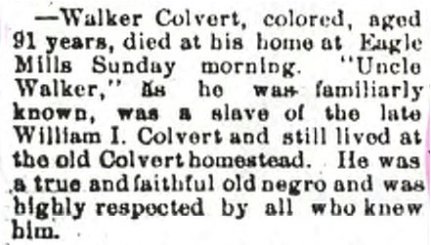

Founded in 1913 as the Wilson Hospital and Tubercular Home, Mercy was one of a handful early African-American hospitals in North Carolina and the only one in the northeast quadrant of the state. Though it struggled financially throughout its 50 years of operation, the hospital provided critical care to thousands who otherwise lacked access to treatment. A small cadre of black nurses assisted the attendant physician. One was Henrietta Colvert, shown below at far left, my great-grandfather’s sister. Henrietta was born in 1893 in Statesville, Iredell County, and received training at Saint Agnes School of Nursing in Raleigh. How she came to Wilson is unknown. This photograph suggests that she cared for Mercy’s patients in its earliest days. (The man seated in the middle is Dr. Frank S. Hargrave, a founder of the hospital, and he left for New Jersey in the early 1920s.) My father’s mother recalled that Henrietta also worked as a visiting nurse for Metropolitan Insurance Company in the 1930s and attended her children for two weeks after they were born. My great-great-aunt was still at Mercy in the 1940s, but had left Wilson by time my mother married my father and moved there in 1961, and my family had long lost contact with her when she died in 1980 in Roanoke, Virginia.

Photograph of Mercy Hospital taken in June 2013 by Lisa Y. Henderson. Photo of Mercy’s staff courtesy of the Freeman Round House Museum, Wilson NC.