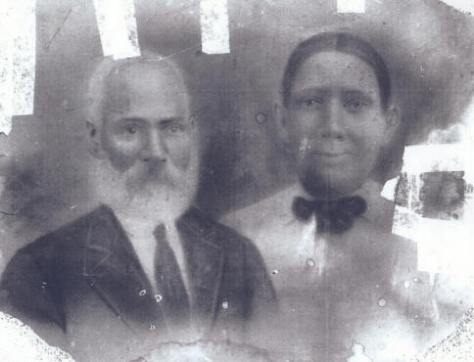

Martin John Locus (1843-1926) and Delphia Taylor Locus (1850-1923). Martin was the son of Martin Locus and Eliza Brantley Locus of southeastern Nash and later western Wilson County. Delphia was the daughter of Dempsey Taylor and Eliza Pace Taylor of northern Nash County.

Martin John Locus (1843-1926) and Delphia Taylor Locus (1850-1923). Martin was the son of Martin Locus and Eliza Brantley Locus of southeastern Nash and later western Wilson County. Delphia was the daughter of Dempsey Taylor and Eliza Pace Taylor of northern Nash County.

——

I knew Locuses (and Lucases, their later variant) growing up. There were a few who actually lived in Wilson, but most were from the western part of the county and Nash County. There is no tradition of Locus ancestry in my family history, and nothing I’ve documented suggests it. However, DNA testing has revealed too many matches with descendants of the Locuses (and related families, like Brantley and Eatman) to ignore. So far:

- R.B.W. is my father’s estimated 2nd-4th cousin. They match on chromosomes 5, 18, 20, 21 and 22, and she lists Blackwell, Eatman, Hawkins and Lucas among her surnames.

- M.F. is my father’s estimated 3rd to 5th cousin. She lists Locus/Lucas, Eatman, Brantley and Howard among her surnames.

- E.F. is author of Free in a Slave Society:The Locus/Lucas Family of Virginia and North Carolina, Tri-Racial, Black-Identified, over 250 Years of History, a compendium of research notes, charts and photographs chronicling one of the largest free colored families in the antebellum United States. He notes that the Locus/Lucases intermarried with several free colored families, including Deans, Wiggins, Pulley, Taylor, Wells, Blackwell, Colston, Richardson, Brantley, Howard, High, Williams, Hagans, Evans, Tayborne, Eatman, Vaughn, Strickland, Jones, Pridgen and Allen. E.F. matches my father on a tiny stretch of chromosome 19 (which I did not inherit); 23andme estimates that they are 3rd to distant cousins.

- T.W.is my estimated 4th-6th cousin per Ancestry DNA. Her father was born in Wilson County and is descended from Locus/Lucases and Evanses (another free family of color).

- T.J. is an adoptee whose birth mother is believed to be a Jones and Locus. She is an estimated 3rd to distant cousin to my father.

What’s the link? I know it’s on my father’s side. Common sense tells me that the most likely connections are:

- Leasy Hagans. Leasy Hagans appears in a Nash County census and may have originally lived north and west of where she settled in Wayne. It is not clear whether Hagans is her maiden or married name. Nor is the father of her children known. Was she, or he, a Locus? An Eatman? A Brantley?

- Tony Eatman. Willis Barnes‘ death certificate lists his parents as Tony Eatman and Annie Eatmon. Tony was born free about 1795 and is listed as a farmer in the household of white Theophilus Eatman in the 1850 census of Nash County. (He also is listed as the groom’s father on the marriage license of Jack Williamson and Hester Williamson in 1868.) One potential problem with Tony as my Locus link, though, was explained here. If Willis Barnes were Rachel Taylor’s stepfather, I am not descended from Tony Eatman at all.

- Green or Fereby Taylor. Delphia Taylor Locus was the daughter of Eliza Pace and Dempsey Taylor, a free man of color born circa 1820 in northern Nash County. His relationship to another Dempsey Taylor in the area is assumed, but has not been proven. One white Dempsey (there were several) was the son of Reuben Taylor and the brother of Kinchen Taylor, Green and Fereby’s owner. There is no tradition of white ancestry among the Taylors, but their Y-DNA haplogroup appears to be J2b1, which is European. Was Green — or Fereby, for that matter — descended from Kinchen Taylor or one of his relatives?

Photo courtesy of Europe Ahmad Farmer.