As my father put it, all the “big dogs” lived on Green Street. The 600 block, which ran between Pender and Elba Streets, two blocks east of the railroad that cleaved town, was home to much of Wilson’s tiny African-American elite. There, real estate developers, clergymen, doctors, undertakers, educators, businessmen, craftsmen — and a veterinarian — built solid, two-story Queen Annes that loomed over the cottages and shotgun houses that otherwise lined East Wilson’s streets. Booker T. Washington slept there.

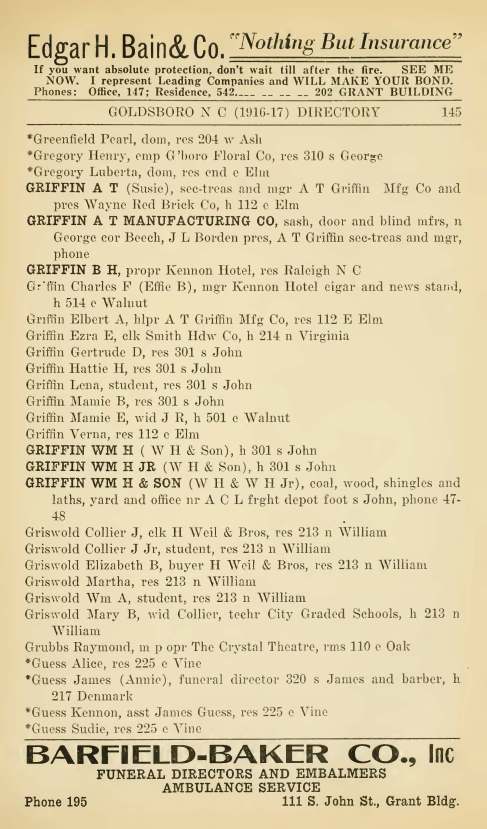

The north side of Green Street as depicted in a 1922 Sanborn map.

During my childhood, a half-century into its reign, Green Street was slipping, home to widowers and dowagers struggling to stay on top of the maintenance and expense imposed by multi-gabled roofs, ranks of single-paned windows, and wooden everything. Still, its historical distinction as black Wilson’s premier residential address held, and a drive down the block elicited a bit of pride and wonder. In 1988, East Wilson, with Green Street its jewel, was nominated for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. Every house on the block depicted above was characterized as “contributing,” and the inventory list contained brief descriptions of the dwellings and their owners. #617, for example, was the Walter Hines house, a two-story “Queen Anne house with hip-roofed central block and projecting cross gables,” and Hines was described as “a prominent barber and property owner.”

Historic status, though, could not keep the wolves from the door. Even as the city’s Historic Properties Commission was wrapping up its work, East Wilson was emerging as an early victim of that defining scourge of the late 1980s — crack cocaine. As vulnerable old residents died off — or were whisked to safer quarters — crackheads and dealers sought refuge and concealment in the empty husks that remained. Squatters soiled their interiors and pried siding from the exteriors to feed fires for warmth. One caught ablaze, and then another, and repair and reclamation seemed fruitless undertakings.

This is the north side of Green Street now. The left edge of the frame is just west of #611. THERE IS NOT ANOTHER HOUSE UNTIL YOU GET TO #623. They are gone. Abandoned. Taken over. Burned down. Torn down. Gone.

[Sidenote: 623 Green Street was built for Albert Gay, a porter at the Hotel Cherry downtown. Albert married Annie Bell Jacobs, daughter of Jesse A. Jacobs, Jr., and their descendants remain in the house. Charles Gay, next door, was Albert’s brother. And around the corner, in the small ell below Pilgrims Rest Primitive Baptist Church, 303 Elba.]

Photograph taken by Lisa Y. Henderson, October 2013.