When James Barnes’ will was probated in 1848 in Edgecombe County, North Carolina, and its provisions carried out, ownership of Howell, an enslaved man, transferred to McKinley Darden. In the 1870 census, Howell Darden, his wife Esther, and their children appear in Black Creek township in Wilson County, North Carolina. Howell had adopted the last name of the family that had owned him most of his adult life. His choice, however, was the not only one available to freedmen. Unbeknownst to slaveowners, many enslaved people claimed surnames even during slavery, though these names were not recognized legally. Some former slaves cemented links to kin by taking the surnames their mothers or fathers used. Others adopted the name of their last master, or reached back to earlier owners, perhaps from their childhood. Still others declined to acknowledge their former bondage altogether, and took names related to a skilled trade, a physical feature, a famous figure, or some other personal idiosyncracy.

Researchers attempting to trace African-American family lines often hit a brick wall at 1870. Having identified an ancestor reported in that census, they invariably ponder the question: how can I find the parents and siblings of this newly freed person? Answering these questions requires flexibility and a willingness to consider indirect sources. Marriage and death records may reveal close familial relationships among people with different surnames. For example, Vicey Artis, a free woman of color, and her enslaved husband Solomon Williams lived separately in the area of northeastern Wayne County and southwestern Greene County, North Carolina. Vicey appears in the 1850 and 1860 censuses with several children named Artis. Vicey and Solomon recorded their cohabitation in 1866, when most of their children were adults. Examination of marriage and death records reveals that some of Vicey and Solomon’s children (who were all free-born) assumed their father’s last name after his emancipation and others (especially the older ones) retained their mothers’. While nothing immediately obvious links Jonah Williams of Wilson and Adam Artis of Nahunta, vital records and other documents establish that they were brothers.

Similarly, upon Emancipation, two of the children of Margaret McConnaughey and Edward Miller, formerly enslaved in Rowan County North Carolina, chose the surname McConnaughey and three, Miller. Margaret and her children had been owned by a McConnaughey. Death certificates, marriage records, and close examination of households in census records provide the clues that establish this family’s connections.

Researchers should also pay attention to groupings of first names. Like whites during the era, former enslaved people often fortified the ties between generations by naming children after relatives. Thus the recurrence of certain given names among a group of families sharing the same surname could indicate kinship. For example, the fact that Benjamin Barnes’ son Calvin, born about 1836, named two sons Redmond and Andrew could indicate a sibling relationship between Benjamin, Redmond and Andrew Barnes, all born circa 1820 and listed near one another in the 1870 census of Wilson County. That the elder Redmond also had a son named Calvin further supports the possibility. In addition, when comparing documents, keeping an eye out for familiar first names may help identify freedmen who changed their surnames, perhaps rejecting one that had been chosen too hastily or that had not chosen for themselves. For example, the Isom, Guilford, Robert, Jackson, and Lewis Bynum who registered cohabitations in Wilson County in 1866 appear in the 1870 census and after as Isom, Guilford, Robert, Jackson and Lewis Ellis.

Also remember that freedmen who shared a surname and common former owner were not necessarily kin. A grouping of one hundred enslaved people may have comprised a dozen or more — many more — unrelated families. For example, Mack Coley of Wayne County, North Carolina, was the grandson of Winnie Coley and of Sallie Coley Yelverton. Several of Winnie Coley’s children were fathered by Peter Coley. Trying to understand how these Coleys — all of whom appear to have belonged to a single former master — relate to one another (or don’t) is a daunting task.

Civil war pension records are another rich source of evidence about naming choices and family ties. Consider this passage from the Confederate pension application of Jim Ellis Dew of Wilson County, North Carolina:

“It was at the time we were making ‘sorgum’ that I was sent to the war. I belonged to my master Mr. Hickman Ellis who married a Miss Dew. You know missus, the white folks are not as strong as the niggers and Mr. Jonathan Dew, brother to my missus, was not very well, and they let him draw a man to go in his place and they drew me. I was sent to Fort Fisher and went to work throwing up breastworks. … We stayed on the island for while. After a while, I came home. While I was in the war I was known as Jim Dew, but when I came back from the war I was called by my old name “Jim Ellis” because I belonged to my missus.”

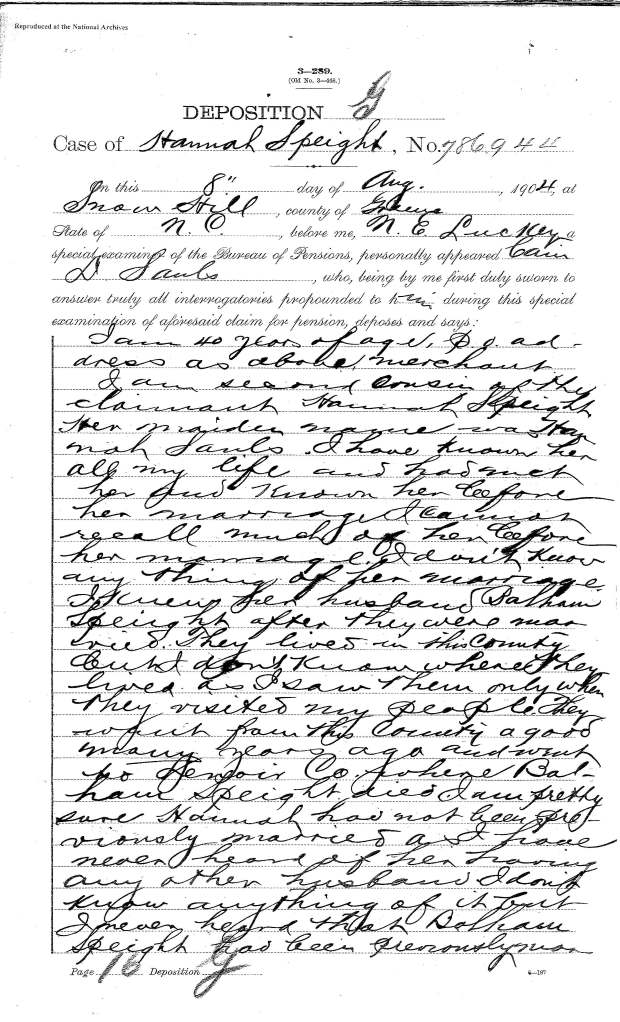

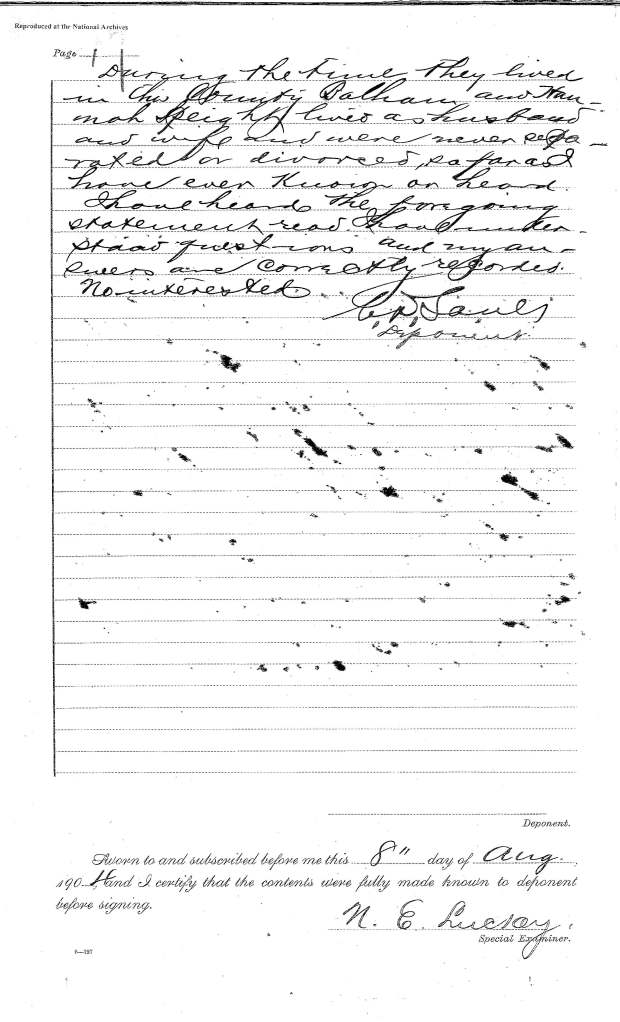

Similarly, the file containing the Union Army pension application of Baalam Speight’s widow Hannah Sauls Speight reveals that Baalam had enlisted as Baalam Edwards, his owner’s surname, but later adopted his father’s surname Speight. His brother Lafayette, on the other hand, had kept Edwards as his name. A witness named Lewis Harper testified that he had a brother named Loderick Artis. (Artis, born enslaved, had taken his free father’s surname.)

Though researching enslaved ancestry is almost always difficult, creative consideration of the available evidence often yields surprising rewards. Marriage records for people born into slavery often show surnames for both parents that are different from the child being married. Cross-reference siblings, and you’ll often find a completely different set of surnames. Be careful when trying to match former enslave people to their kinfolk and their masters. Reasons for choosing names were varied and inscrutable, and people tried on different identities for a few years. Empowering for them — maddening for us!

(For a more in-depth analysis of slave naming practices and patterns, see Eugene D. Genovese’s Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made and Herbert Gutman’s The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom.)