And why have I never been able to find the marriage license of my great-grandfather Lon W. Colvert to his first wife?

Because: Cottrell.

Here is the entry in an Iredell County Indexed Register of Marriages. Ancestry.com rides to the rescue again.

And why have I never been able to find the marriage license of my great-grandfather Lon W. Colvert to his first wife?

Because: Cottrell.

Here is the entry in an Iredell County Indexed Register of Marriages. Ancestry.com rides to the rescue again.

As I discussed here, my great-great-grandmother Harriet Nicholson Tomlin Hart had two half-brothers named William. I discovered her mother’s son, William H. Nicholson, in the 1900 census. The newly widowed Harriet and her young son Golar — the only one of her Tomlin children to see the 20th century — were living in her brother’s household in Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. With this information, I found William’s 1909 death certificate. Harriet was the informant, and she listed his parents as Burwell Carson and Lucinda Nicholson. Other than a few city directory listings, this was the only documentation of William that I had until last night, when I found this:

It’s hard to read, but it’s a Mecklenburg County marriage license for William H. Nicholson. On 3 April 1884, he married 38 year-old Lizzie King of Charlotte.

… William had a wife?

I went back to the 1900 census and examined it more closely. At 611 East Stonewall, William “Nickolson,” age 51, plasterer; Harriet Tomlin, 38, his sister; and Golda, 6, his niece. (Actually, his nephew.) Harriet was described as a widow, with only one child of ten living. (This is not quite right either, as her oldest child Lon was also alive, but 80% mortality versus 90% is meaningless.) William, in fact, is described as married, but there is no wife in the household. Where was Lizzie Nicholson?

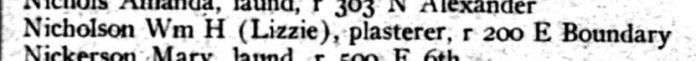

I searched further. More city directories have been digitized since last I looked, and I quickly found several entries from the latter half of the first decade of the 1900s. Here’s one:

Walsh’s City Directory for Charlotte, North Carolina, 1907.

Walsh’s City Directory for Charlotte, North Carolina, 1907.

If there had been a rough patch around 1900, it was smoothed over within a few years. William’s 1909 death certificate describes him as married (though his sister came all the way from Statesville to provide information.) Lizzie died just a year later.

I went back further. I’d seen city directory listings for William Nicholson in Charlotte in 1890 and 1891, but last night I found a couple like this:

A Directory of the City of Charlotte, North Carolina for 1896 and 1897.

A Directory of the City of Charlotte, North Carolina for 1896 and 1897.

Same occupation, same address, same wife. This appears to be William using his middle name, Henry. I found others: in 1889, Henry Nicholson, brickmason, and Lizzie Nicholson, cook at the Central Hotel, living at 611 East Stonewall. In 1897, Henry H. Nicholson, laborer, and Lizzie Nicholson at the Stonewall address. The entry below: Nicholson & Allen (c) [for “colored”] (Lizzie Nicholson & Richard Allen), proprs Northern Rest, 220 East Trade. In 1904: Henry Nicholson (Isabella), plasterer, 611 E Stonewall.

A Newspaper.com turned up nothing on William Henry, but there were several notices published in late 1910 and early 1911 regarding Lizzie Nicholson’s estate, and a delinquent property tax listing in 1894 that reveals that she was the owner of the Stonewall address. Levine Museum of the New South’s People of 1911 Charlotte project depicts the Sanborn drawing of this one-story house on an unpaved street and lists its owner at that time as Montgomery Caesar. The Second Ward street is no longer residential, and 611 is just a block from the NASCAR Hall of Fame. East Boundary Street, William and Lizzie’s other address, is gone. And 220 East Trade is now the Epicentre.

When Northern Restaurant was, though, a small but confident ad:

Charlotte Observer, 16 September 1896.

Then, less charitably:

Charlotte Observer, March , 1897.

Charlotte Observer, 8 October 1897.

So, to update what I know about Harriet’s brother:

William Henry Nicholson was born between 1842 and 1848 to Lucinda Nicholson and Burwell Carson. His whereabouts in 1870 and 1880 are unknown. He was trained as a brickmason and plasterer and plied both trades in Charlotte. In 1884, he married Lizzie King (whose first name was possibly Isabella). It was at least her second marriage. (Her parents’ names on the license are nearly illegible, but they are not “King,” and she is referred to as Mrs. in the document.) Lizzie worked as a cook at a hotel, and then at her own establishment, Northern Restaurant, which she co-owned with Richard Allen. Perhaps before her marriage to William, Lizzie bought or inherited a house at 611 East Stonewall in Charlotte. For a brief period around 1900, William’s half-sister Harriet lived at the Stonewall house. By 1907, William and Lizzie had moved to 200 East Boundary, and each of them died in the house there. William died in December 1909, and Lizzie not quite two months later in February 1019.

… the elusive Aunt Ella.

Back before I completely fell off the 52 Ancestors Challenge, I wrote a piece about my great-great-grandmother Loudie Henderson‘s sister Louella. The gist of it was that, other than the 1880 census and my grandmother’s recollections, there were no sure sightings of this woman. But Ancestry’s new North Carolina Marriages collection is paying off for me in a big way, and the first cha-ching was Aunt Ella’s license for her marriage to William James Laws in 1931. The collection is indexed by parents, as well as bride and groom, and a search for James Henderson picked the record up. I’m elated, but thrown. The last husband my grandmother remembered was Wilson, but he clearly was not the end of the line for Ella. (And 40? Please. By 1931, she was pushing 55.) The witnesses: is that “Mary” Smith? Or “Nany” Smith, i.e. Nancy “Nannie” Henderson Smith Diggs, Ella’s sister. Nancy’s second marriage, to Patrick Diggs, was short-lived, and in the 1930 census, she had reverted to Smith. And which A.M.E. Zion church?

Just when I thought I’d gotten tangled up in enough questions, I found this:

Rastus Best?!?! Aunt Ella was married yet another time? And where are the licenses for the husbands — King and Wilson — I thought I knew? And Disciple Church?

So. Louella Henderson King Wilson Best Laws moves to the top of my “get to the bottom of this” list. A quick search for a Laws death certificate turned up nothing, but I’m hot on her trail.

Ancestry.com recently launched North Carolina County Marriage Records, a date collection that includes images of marriage bonds, licenses, certificates and registers from 87 counties. (Including all of mine!) I’ve already stumbled across two previously unseen records for distant cousins, aunts or uncles, and I anticipate filling in gaps with many more that I managed to overlook over the years.

As a sample of the value of these records, here’s a single page from one Wayne County marriage register:

1. James Aldridge, 70, married Eliza Thompson. Just about every “colored” Aldridge in 19th century Wayne County is a member of my extended family, but this one doesn’t seem to be one of mine. I can’t place a James born circa 1832. Perhaps this man came into the county from Lenoir or Duplin, which had slave-holding Aldridge families.

2. Adam T. Artis, 68, to Katie Pettiway, 20. This was my great-great-great-grandfather’s last marriage. He was actually 71, rather than 68, so Katie was more than 50 years his junior. (And her maiden name was actually Pettiford.) I’ve written about their family here. (By the way, more about their officiant, Rev. Clarence Dillard (5) here.

3. Robert Artis, 20, to Christiana Simmons, 18. Robert Artis was a son of Adam and Amanda Aldridge Artis. His witnesses may have been his cousin Jesse Anthony Artis, son of Jesse Artis, and uncle William Artis.

4. Robert Aldridge, 37, to Rancy Pearsall, 31. My great-great-grandfather John W. Aldridge‘s second youngest brother Robert finally married in 1903. He and Rancy (or Rannie) adopted a son, Bennie, born in 1908, and she died before 1916, when Robert remarried.

——

They’re not exactly brick walls, but this one data collection has revealed this and this and this and this…

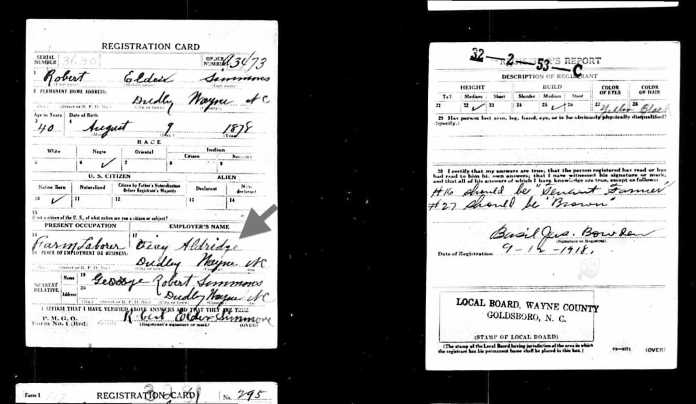

Sometimes you’ll run across a little extra information in an unexpected place.  I’m not related to Robert E. Simmons. But I’m connected to him a couple of ways. As the son of George R. and Mary McCullin Simmons, he was (1) the nephew of my great-great-uncle Lucian Henderson‘s wife Susie McCullin Henderson and (2) the nephew of my great-great-aunt Ann Elizabeth Henderson Simmons‘ husband Hillary B. Simmons. While researching for Robert’s great-niece, I found his World War I draft registration card and in it a little glimpse at my great-great-grandmother Vicey Artis Aldridge‘s life after her husband John’s death in 1910. Per the correction on the back of the card (at right), Robert Simmons was a tenant farmer on Vicey’s land. Under this arrangement, Robert would worked in exchange for rent in the form of cash or a fixed portion of the crop he raised. The arrangement may also have included housing for Robert and his family and a small wage if he had additional responsibilities. Typically, though, a tenant farmer provided his own equipment and animals. (Farm laborers, on the other hand, were hired hands working for wages.)

I’m not related to Robert E. Simmons. But I’m connected to him a couple of ways. As the son of George R. and Mary McCullin Simmons, he was (1) the nephew of my great-great-uncle Lucian Henderson‘s wife Susie McCullin Henderson and (2) the nephew of my great-great-aunt Ann Elizabeth Henderson Simmons‘ husband Hillary B. Simmons. While researching for Robert’s great-niece, I found his World War I draft registration card and in it a little glimpse at my great-great-grandmother Vicey Artis Aldridge‘s life after her husband John’s death in 1910. Per the correction on the back of the card (at right), Robert Simmons was a tenant farmer on Vicey’s land. Under this arrangement, Robert would worked in exchange for rent in the form of cash or a fixed portion of the crop he raised. The arrangement may also have included housing for Robert and his family and a small wage if he had additional responsibilities. Typically, though, a tenant farmer provided his own equipment and animals. (Farm laborers, on the other hand, were hired hands working for wages.)

In October 1998, I received an email from P.M., who was seeking information about her Simmons forebears. During the antebellum era, the Simmonses were a large free family of color in Duplin and Wayne Counties. Though I am not one, I’ve researched them both in my free people of color work and because several Simmonses have intermarried into my lines. I quickly identified P.M.’s great-grandfather, George Robert Simmons, as the son of George W. and Axey (or Flaxy) Jane Manuel Simmons and, accordingly, brother of Ann Elizabeth Henderson Simmons‘ husband Hillary B. Simmons. I was also able to provide information about her Artis line, but came up blank when she mentioned her great-grandmother, Mary McCullin Simmons. Then: “Mary’s sister Susie married a Lucien Henderson,” P.M. wrote. “I think they lived in Dudley. My mother remembers visiting her when she was a little girl. Does his name ring a bell?”

It did indeed. James Lucian Henderson, whom I’ve written about several times, including here and here, was my grandmother’s beloved great-uncle. In the hours I recorded her talking about her people, my grandmother mentioned Aunt Susie several times:

And A’nt Susie was real light, and her hair was all white, and she’d plait it in little plaits, and then tuck ’em up. It didn’t grow that much, ’cause it wasn’t long. And she had a rag on her head all the time. Only time she’d comb it was — when she’d be combing her head, you’d see it. And it was just about like this. [Indicates the length of two finger joints.] Shorter than this. I don’t know whether she cut it off or not. But it didn’t grow, and it was white, and she’d put that rag back around her head. After she’d comb her hair. And it was doing like that all the time. Shaking. Her head was shaking, and I asked Mama, “What’s wrong with her?” How come her head was shaking all the time? And she said, “Well, it’s a sickness.” She said, “I don’t remember what they call it.” So I didn’t say nothing else about that. I used to go down there. She couldn’t cook. Like over the stove, like cook dinner, after twelve o’clock. Had to cook it before twelve o’clock before it got too hot. Because she couldn’t be over the stove, she’d fall out, if she was over the stove. So Uncle Lucian always got up and cooked breakfast.

So we come up there and stay, and Aunt Susie, she’d be out there in the yard to the pump or something. I never did see her with her hair. She’d always have a pocket handkerchief, look like, tied to the corner and out it up on her head and tuck it up under her hair. And it was white like cotton. And so, I don’t think she ever left the house. See Uncle Lucian always went to church right up there from the house. I don’t know what the name of Uncle Lucian’s church was. It had a funny name, but I don’t know whether it was Methodist or Baptist, but she didn’t go to church. She never left the house that I know of. I told Mama, “She’s gon shake her head off.” She said, “It was a palsy, that’s how come.” I said to Mama, I said, “That thing’s gon shake her head off.” And I said, ‘Hmm, why she have a rag on her head all the time and her head just shaking like that?’ It be a white rag up there. I wanted to ask her so bad. But I didn’t. Didn’t never ask her.

I recently heard from P.M. again and pulled out our old correspondence. Here’s what I now know about the McCullins:

Rose (or Rosa) McCullin was an enslaved woman born perhaps 1825. She is believed to have been enslaved by Calvin J. McCullin or his brother Benjamin F. “Frank” McCullin in Buck Swamp township, Wayne County, and to have been the mother of at least four daughters – Jane, Mary, Susan and Virginia – by Frank McCullin. Rose McCullin appears in no census records and seems to have died before 1870. The only known references to her are on the marriage and death records of her children, as detailed below.

Jane McCullin

Mary Ann McCullin

Susan McCullin

Marriage license of Lucian Henderson and Susan McCullin, Wayne County Register of Deeds.

Virginia McCullin

Interview of Hattie Henderson Ricks by Lisa Y. Henderson, all rights reserved.

The seventh in an occasional series excerpting testimony from the transcript of the trial in J.F. Coley v. Tom Artis, Wayne County Superior Court, November 1908.

Defendant introduces JESSE ARTIS who being duly sworn, testified:

I had a conversation with Tom Artis and Hagans about this land. I was working there for Hagans (Plaintiff objects) as carpenter. Tom Artis was working with me. The Old man Hagans was talking to Tom about claim which Mrs. Exum had on his land, and was telling him that he had some money at that time, and was would take it up if he wanted to, and give him a home for his lifetime. He left us, and Tom talked to me. I told him he did not know whether he would have a home all his life or not. I advised Tom to let Hagans take up the papers, and Tom did so. Hagans told me next day that if Tom should pay him 800 lb. of cotton he should stay there his life time. When he paid him his money back, the place was his. I don’t know that Tom and I are any kin. Just by marriage. We are not a member of the same Church.

CROSS EXAMINED.

When I was a carpenter ‘Pole told me all about this on his place. He took me into his confidence. I don’t know whether he told me all. He told me a good deal.

——

Jesse Artis (circa 1847-circa 1910) was a brother of my great-great-great-grandfather Adam Artis and his brother Jonah Williams, the latter of whom also testified in this trial.