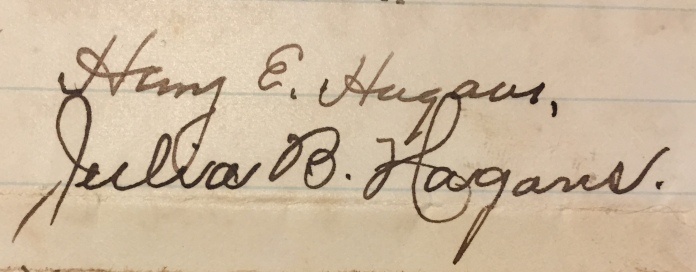

Napoleon Hagans, self-made man, could neither read nor write. His wife, Appie Ward Hagans, born into slavery, picked up the rudiments of an education at some point in her life and was able to scratch out a shaky signature, as shown in this 1888 deed. By time his sons were born, Napoleon had begun his ascent into Wayne County’s African-American elite, recognized by both blacks and whites as a savvy and successful cotton farmer. Thanks to his wealth, the children he reared, Henry and William Hagans, would lead lives very different from their father’s, starting with their educations at local schools and then Howard and Shaw Universities. Henry E. Hagans spent much of his life as a teacher and principal, and his small, firm hand reflects his pedagogical life. He likely met his wife, Julia B. Morton of Danville, Virginia, at Howard. This sample of their signatures is on a deed dated 1899.

Henry E. Hagans spent much of his life as a teacher and principal, and his small, firm hand reflects his pedagogical life. He likely met his wife, Julia B. Morton of Danville, Virginia, at Howard. This sample of their signatures is on a deed dated 1899.

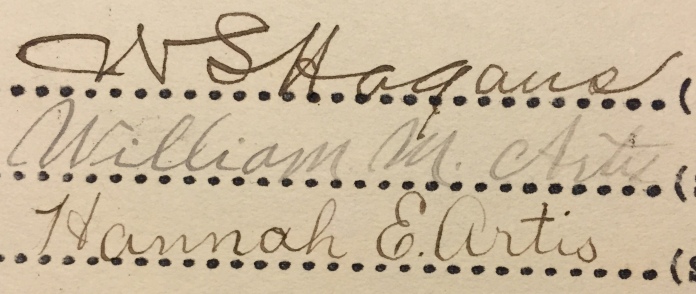

William Hagans’ signature was bolder and more architectural than his brother’s, as shown on the 1916 deed below. Though not a teacher, his early career as secretary (read: assistant or even chief of staff, if there was additional staff) to United States Congressman George H. White and as businessman/farmer provided ample opportunity for him to display his conjoined signature. (William M. Artis, son of Adam T. and Frances Seaberry Artis, was William Hagans’ first cousin, and Hannah E. Forte Artis was the wife of William Artis’ brother, Walter S. Artis. William likely did not attend school beyond eighth grade, but his penmanship is lovely. Hannah, too, clearly benefitted from several years of schooling. I wish I knew more about late 19th century rural African-American schools in Wayne County.)

William Hagans’ signature was bolder and more architectural than his brother’s, as shown on the 1916 deed below. Though not a teacher, his early career as secretary (read: assistant or even chief of staff, if there was additional staff) to United States Congressman George H. White and as businessman/farmer provided ample opportunity for him to display his conjoined signature. (William M. Artis, son of Adam T. and Frances Seaberry Artis, was William Hagans’ first cousin, and Hannah E. Forte Artis was the wife of William Artis’ brother, Walter S. Artis. William likely did not attend school beyond eighth grade, but his penmanship is lovely. Hannah, too, clearly benefitted from several years of schooling. I wish I knew more about late 19th century rural African-American schools in Wayne County.)