Cousin C.D. Sauls‘ primary business:

The Great Sunny South (Snow Hill NC), 11 February 1898.

Goldsboro Messenger, 10 March 1884.

Goldsboro Messenger, 11 September 1884.

Solomon Williams‘ son (and estate administrator) Jonah Williams placed these notices in a local newspaper. Solomon’s six acres could not be meaningfully divided among the eight children that survived him. Ruffin Bridge is another name for Peacock’s Bridge, which spans Contentnea Creek on the Wilson-Greene Counties border. It is not at all clear to me, however, which road would have been regarded as the road from Goldsboro to the bridge.

Goldsboro Headlight, 16 August 1900.

I don’t which Winn this is, but I am certain the Aldridge is my great-grandfather’s brother, John J. Aldridge. Here’s his World War I draft registration card, filed 17 years after this article was published:

(I’ve always wondered about the “skull broken about 12 years ago.”) Johnnie Aldridge not only recovered, but lived another 64 years after his horrific injury.

John J. Aldridge (1887-1964), son of John W. and Louvicey Artis Aldridge.

As reported in the 2 June 1932 edition of the Pittsburgh Courier, my great-uncle J. Maxwell Allen did a little acting while at seminary:

(Coincidentally, his middle brother’s first child, my Aunt Marion, was born that day.)

Angeline McConnaughey‘s mother Caroline may have lived long enough to breathe the sweet air of freedom, but not deeply. By 1870, she was gone, and her only child is listed in the census that year with Caroline’s mother, Margaret McConnaughey. By 1875, Angeline had left the Mount Ulla countryside for the town of Salisbury and in February of that year she married Fletcher Reeves, the 21 year-old son of Henry and Phrina (or Fina) Overman Reeves. With unusual candor, Angeline named her father on her marriage license. He was Robert L. McConnaughey of Morganton, white and a relative of Angeline’s former owner, James M. McConnaughey.

Angeline Reeves gave birth to her first two children, Caroline R. (1875) and M. Ada (1878), in Salisbury. The Reeves had plans bigger than that town could hold, however, and shortly after 1880 the family settled at 409 East Eighth Street in Charlotte’s First Ward, a racially integrated, largely working-class neighborhood in the city’s center. Fletcher Reeves went to work as a hostler for John W. Wadsworth, who climbed to millionaire status with his livery stables even as Charlotte’s first electric streetcars were poised to dramatically transform the city’s landscape. In short order, three more children — Frank Charles (1882), Edna (1884) and John Henry (1888) — joined the household, and Angeline took in washing to supplement the family’s income.

Fletcher and Angeline’s combined incomes created a comfortable cushion for their children. On 1 March 1894, in an article snarkily titled “A Fashionable Wedding in Colored High Life,” the Charlotte Observer identified Carrie Reeves, accompanied by Cowan Graham, as a bridal attendant at the marriage of Hattie L. Henderson and Richard C. Graham, “one of the best and most popular waiters at the Buford Hotel.” The ceremony was held at Seventh Street Presbyterian Church and “‘owing to the prominence of the contracting parties,’ a number of white people were present.” Carrie herself was a bride eight months later when she married James Rufus Williams. Her sister Ada’s nuptials, in March 1895, were announced in the March 14 edition of the Observer: “Frank Eccles and Ada Reeves, colored, were married Tuesday night. The groom is Farrior’s man ‘Friday.’ He is a good citizen and deserves happiness and prosperity.”

By 1900, the Reeveses were renting a house at 413 East Eighth. Fletcher continued his work as a “horseler,” but Angeline reported no occupation, apparently having withdrawn from public work. Eighteen year-old son Frank worked as a porter, and youngest children Edna (15) and John (11) were at school. On 21 August 1902, Frank made an ill-starred marriage to Kate Smith. Two and a half years later, his sister Edna married William H. Kiner of Boston, Massachusetts.

When the censustaker returned in 1910, he found Fletcher and Angeline still living in the 400 block of East Eighth. All of their children had left the nest, and in their place was 7 year-old grandson Wilbur Reeves, who was probably Frank and Kate Reeves’ child. If the boy found comfort and stability in his grandparents’ home, however, it was not to last. On 4 September 1910, Fletcher succumbed to kidney disease. He was buried in Pinewood Cemetery, and Angeline went to live with her oldest daughter’s family.

In the 1900 census, Rufus and Carrie Williams and sons Worth (5) and Hugh J. (2) shared a house at 419 Caldwell Street with Frank and Ada Eccles and their son Harry. Rufus, who owned the house, worked as a hotel waiter and Frank as a day laborer. In 1906, Carrie posted a series of ads in the Charlotte News seeking customers for her sewing business.

Charlotte News, 5 September 1900.

Rufus seems to have spent his free team pitching for a top local baseball team:

Charlotte News, 13 August 1900.

Charlotte News, 4 September 1900.

In the 1910 census, the family is listed at 212 West First Street. Rufus worked as a porter at a club and Carrie as a seamstress. Sons Worth (14) and Jennings (12) were students. Ada Eccles, already a widow, had migrated to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is listed at 8 Rockwell Street with brother-in-law William H. Kiner, sister Edna E. and their children Addison F. (4) and Carroll M. (2), plus brother John H. Reeves. William worked as a clothes presser in a tailor shop, Ada as a servant, and John as a hotel waiter. William was born in Virginia, all the others except Carroll in NC. (The Kiners also spent time in Oak Bluffs, on Martha’s Vineyard. Son Carroll Milton was born there in 1907; the birth register gave William’s occupation as theological student.) Frank is not found in the 1910, but the state of his marriage can be inferred from a newspaper article about his wife, passing for white in Hollywood.

Charlotte News, 15 May 1910.

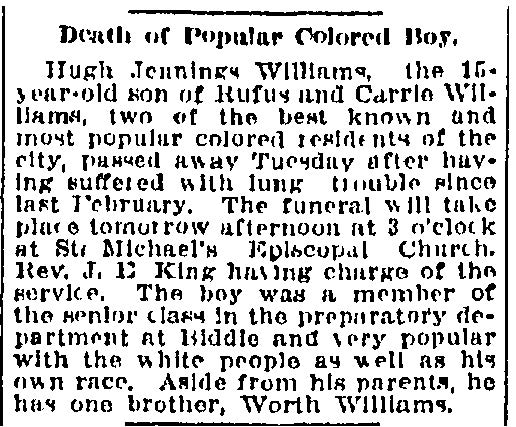

Hugh Jennings Williams died after a battle with tuberculosis in 1913, during his final year in Biddle University‘s preparatory division. (His older brother, Worth Armstead Williams, also attended Biddle for high school and college.) Jennings’ obituary paints a charming picture of the boy and makes clear his parents’ status in the eyes of white Charlotte.

Charlotte News, 20 November 1913.

Just months later, more than 800 miles away in Cambridge, Jennings’ uncle John H. Reeves also contracted TB. He was dead by April 1915.

By 1920, the Williamses had moved a little ways out of the heart of the city to 826 South Church Street in the Ninth Ward. Widow Angeline Reeves was listed in the household with Rufus, Carrie, and 24 year-old Worth Williams. Rufus was a porter at a club, Carrie was a dressmaker, and Worth a student at a dental college. (Worth was only at home temporarily. He was enrolled at Howard University’s dental school.)Meanwhile, up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the censustaker found William H. Kiner (a chipper at a shipyard), wife Edna E., and children Addison F., Carroll M. and Evelyn C. living at 8 Rockwell Street, and Ada Eccles and her son Harry at 65 Grigg Street.

Rufus Williams continued to enjoy the esteem of his employer and patrons at the Southern Manufacturers Club — at what personal cost unknown. Waiting on the cream of the Queen City’s burgeoning manufacturing magnates was a path to economic security, but that path was strewn with daily indignity, both casual and intentional. Rufus, and his father before him, were what some fondly called “white man’s niggers,” but to acknowledge this is not to indict them. In a 1924 news article, note that Rufus’ speech honoring his benefactor, John C. McNeill, also shines a light on the fruit of his years as a servant — his “son, W.A. Williams, who is a surgeon dentist at New Bern.”

James Rufus Williams died 24 May 1947 in Charlotte. Six years later, on 25 March 1953, his mother-in-law Angeline McConnaughey Reeves passed away at the age of 94. Her mother and husband gone, Carrie Reeves Williams lived just six months more and died 28 September 1953. I have not found record of Frank Reeves’ death. His sisters Edna Reeves Kiner died in New York City in 1969 and Ada Reeves Eccles in Cambridge in 1979.

So, was he James Garfield Smith or James Garfield McNeely?

Addie Lucinda McNeely married Daniel Smith in Statesville NC on 2 October 1902. Their daughter Ardeanur Smith was born the following February and son James Garfield Smith on 11 April 1906. I have never found the family in the 1910 census and do not know how long Addie and Daniel remained together. When her uncle Julius McNeely’s estate opened, Addie Smith with her siblings was listed as one of the heirs. Unlike her married sisters, however, her husband’s name does not appear alongside hers. In 1917, mid-proceedings, Addie died — I’ve never found her death certificate either — and her name was struck through and was replaced by that of her children, “Ardenia” and James Smith.

I have not located James again with any certainty before 1942. (There’s a “James McNeelly” of the right age listed in the 1930 census of High Point NC, but he had a wife, which my James allegedly never had.) When he registered for the World War II draft, James gave his name as “James Garfield McNeely.” Why the shift from “Smith,” which he apparently never used as an adult? Though his birth year appears to be off by one year, this is clearly our man. He was born in Statesville, and Janie McNeely, his mother’s youngest sister, is named as his contact. (The neighborhood in which he lived and worked is now part of the Washington Street Historic District, and Club Carolina merited a brief mention in the application for historic status.)

Cousin James disappears from the record again until his death certificate was filed. He was working at a pool room and living at the Kilby Hotel when he died. Ardeanur Hart of Jersey City NJ was informant and gave her brother’s name as James Garfield McNeely.

Here’s his obituary:

High Point Enterprise, 21 October 1960.

And a note of acknowledgment from his family. (Who in the world were the Martins and Griffins?):

High Point Enterprise, 13 November 1960.

[Sidenote: The physician who signed James’ death certificate? Dr. O.E. Tillman? His son and I met in high school and became good friends in college. He married A.B., my roommate and closest college friend, and I was in their wedding. Dr. Tillman is now retired, but remains active in High Point civic affairs.]

Goldsboro Messenger, 30 March 1885.

Apparently, Napoleon Hagans was a big believer in insurance. The Insurance Press compiled life insurance claims paid out on a weekly basis, state by state. In the 9 September 1896 issue, the sole listing for North Carolina was: Fremont, Napoleon Hagans, $5000 — the payment he received after his wife Appie Ward Hagans’ death.

My earliest memory: I am wrapped in a red blanket, slightly faded, edged in satin. The air is chilly. The light, low and pink-gold. It is morning, and I am being carried across the street to Miss Speight and Mr. Kenny’s house. They lived at 1400, and we lived at 1401, and I cannot be more than two years old.

My mother says that I cannot remember this. It must be an implanted recollection. I don’t think so, but perhaps. There is no question, though, that I retain other vignettes from the brief time that Nina Speight kept me: a canister of Morton salt on a kitchen table; a bag of wooden blocks on a shelf; a Maxwell House can brimming with snuff juice; a thin chenille spread over a four-poster bed; the dimness of the back room shared by the Speights’ teenaged grandsons. We left Carolina Street when I was nine, but my memories of my years at the edge of East Wilson are warm and tinged with gold. Miss Speight and Mister Kenny loved and nurtured me early and rooted me firmly in the traditions of a Southern community in transition. They passed away within months of each other in 1982 — ironically, the year that I, too, left Wilson, for college.

Nina and Kenneth Speight.

——

Nina Darden Speight was born in 1901 in Black Creek township, Wilson County, to Crawford F. and Mattie Woodard Darden. Her family names indicate deep roots in southeastern Wilson County, which was part of Edgecombe before 1855. Her father, born about 1869, was the youngest of several children born to Howell Darden and Esther (or Easter) Bass, and the only child born free. (Esther’s maiden name also appears as “Jordan” on the marriage license of one of her children.) On 11 August 1866, Howell and Easter registered their cohabitation with a county justice of the peace and thereby legalized their 18-year marriage. Their older children included Warren (born circa 1849, married Louisa Dew), Eliza (born circa 1852, married Henry Dortch), Martin (born circa 1853, married Jane Dew) and Toby Darden (born circa 1858.) Esther Darden died 1870-1880, and Howell Darden between 1880 and 1900.

Evidence that Howell Darden and Esther Bass were both owned by James A. Barnes may be found in the abstract of his will, dated October 14, 1848 and probated at February Court, 1849 in Edgecombe County. Among other property real and personal, Barnes’ wife Sarah received a life interest in several slaves — Mary, Esther and Charles — whose ownership would revert to nephew Theophilus Bass upon her death. To McKinley Darden, Barnes bequeathed “Negro Howell.” [Other enslaved people mentioned in Barnes’ will included Tom, Amos, Babe, Silvia, Ransom, Rose, Dinah, Jack, Jordan, Randy, Abraham, Rody, Alexander, Bob and Gatsey (the only slave to be sold.) Their relationships to Esther and Howell may never be known.]

Nina Speight’s mother Mattie Woodard Darden was born about 1873 in Wayne County to William and Vicey Woodard. She died 7 May 1935 in Wilson County. Crawford Darden died 3 August 1934.

Kenneth Speight was born about 1891 in Speight Bridge township, Greene County, North Carolina, to Callie and Holland Speight. (Some records show a 1899 or 1900 birth year, but he appears in the 1900 census as an 8 year-old.) His father Callie was born about 1855; his mother Holland, about 1860. Callie was the son of Callie (1825) and Allie Speight (1827). In the 1870 census of Greene County, the Callie and Allie Speight’s family is listed next to a wealthy white farmer named Abner Speight, who may have been their former owner.

In 1902, the Charlotte Observer ran an article by C.S. Wooten of LaGrange, North Carolina, “Old Southern Families: Farmers of Wayne and Greene,” a reminiscence about the “old plantations” and “typical Southern gentlemen” of those parts, including Abner Speight:

James Speight, a nephew of Jesse Speight, was Senator for Lenoir and Greene counties for ten years before the war. He married a niece of my father, Maj. Wooten. He was a splendid stump speaker, and I have seen him debate with lawyers on the stump and get the best of the discussion, indeed in those days the best politicians were farmers. His house was a nice place to visit. He always had a special brand of apple brandy made by Col. C.W. Stanton who could make as good brandy as was ever made. Edwin G. Speight, his cousin, was also Senator from Greene and Lenoir counties from 1842-1852. I was a small boy when he was a public man, but I have heard my father say he was a fine speaker and was a natural orator. His second wife was a daughter of Hon. Jake H. Bryan, of Raleigh, and he removed to Alabama where he died a few years ago. Abner Speight, a cousin of the above, was a large farmer, was a noble man and as good a citizen as the State ever had. He had two boys killed in the army, both bright, gallant young men. I have sometimes thought, suppose the South had not been checked in her onward march of prosperity and greatness what would we have been today. I have also thought that the gallant men, the flower of Southern chivalry that were sacrificed in that unhappy struggle were in vain, but I reckon not, for they by their gallantry and valor, have shed unfading justice upon Southern arms and have given her a name that will never be surpassed in the annals of mankind.

Callie and Holland Speight married about 1878, but little else is known of her. After Holland’s death just after 1900, Callie married Minnie Speight (1894-1947), daughter of Stephen and Dillie Woodard Speight, also of Greene County. In addition to Kenneth, Callie Speight’s children included Martha, Mary, Clara, Irwin, Charlie, Callie, Addie, Claud, Mary, Nancy, Flossie, Lewis, Clarence, Effie, Bessie, Pauline, George, Adell, Joe, James and Junius. Callie died after 1940.

——

Postscript: After I posted this piece, the Speights’ grandson, whom I played with on his childhood visits from New York City, sent me another photograph. Nina Darden is standing at top left, holding a flower. Thanks, Tyrone, for both images!

Goldsboro Messenger, 19 November 1885.

Phillip R. Coley, son of Winnie Coley, was the half-brother of Napoleon Hagans‘ son William M. Coley and Adam T. Artis‘ children Cain Artis and Caroline Coley Artis. Richard Artis was Adam T. Artis’ brother, and Simon Exum was his brother-in-law, husband of Delilah Williams Exum. Peter Coley may have been Phillip Coley’s father.