My parents celebrate 54 years of marriage in May, God willing. They have always been my model of deep and enduring love, and I have celebrated them here. For this week’s Ancestor Challenge, I’ve chosen to highlight a different kind of love.

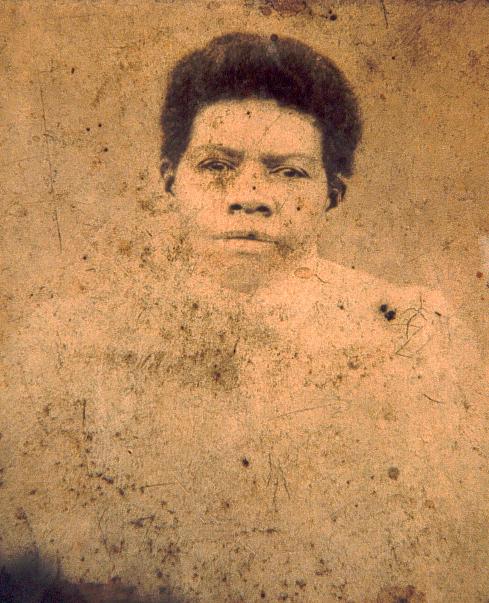

My grandmother, Hattie Mae Henderson Ricks, and her sister, Mamie Lee Henderson Holt, were born into difficult circumstances. Their mother Bessie Lee Henderson, teenaged and unmarried, had been orphaned as a toddler. When Bessie died months after Hattie’s birth, the family gathered to decide who would rear the girls. Mamie remained in Dudley with their aged great-grandparents, Lewis and Margaret Henderson, and Hattie went to Wilson to live with their grandmother’s sister, Sarah Henderson Jacobs. They were not reunited until Grandma Mag’s death, when Mamie was 8 and Hattie, 5. They separated again just 7 years later, when Mamie married a young man she met while visiting relatives in Greensboro. Nonetheless, despite the short time they lived together in childhood, my grandmother and her sister were devoted to one another. Their fierce sisterly bond defied the uncertainty of their earliest years and the emotional neglect of their years with Mama Sarah. It knit their children and grandchildren in a web that continues to hold. Even my grandmother’s move to Philadelphia in 1958 did not shake it. Every Christmas, she visited us and my aunt’s family in Wilson, then my father drove her to Greensboro to bring in the New Year with the Holts. Eventually, Alzheimer’s began to claim Aunt Mamie’s mind and memories, and travel became too difficult for my grandmother, but her attachment did not waver. Only when Aunt Mamie passed did my grandmother begin to let go. Nine months later, almost to the day, she was gone.

After my grandmother passed in 2001, I found a note she wrote about her early life: Heart Broken Mother – Bessie Died age Nineteen Leaving two out of wedlock Girls arounds 3 years and 8 months old. … My sister and I always felt very close to each other as we had no real parents It had been a hard life for both of us

This is the love I celebrate in this week’s challenge. The first love that comes with family. The love that, if we are fortunate, endures the entire arc of life.

Mamie and Hattie Mae Henderson, circa 1920.

The sisters, probably in Greensboro, 1940s.

The sisters on Aunt Mamie’s porch in Greensboro, probably late 1980s.