Baltimorean Attends Services for Father.

CHARLES CITY COUNTY, VA. – Memorial services for the late Stephen Whirley, who served as deacon at the New Vine Baptist Church for 47 years, prior to his death seven years ago, were held Memorial Day at the church.

Among the out-of-towners attending was a son, John Whirley, proprietor of Club Ubangi café and nightclub in Baltimore. — Baltimore Afro-American, 4 Jun 1949.

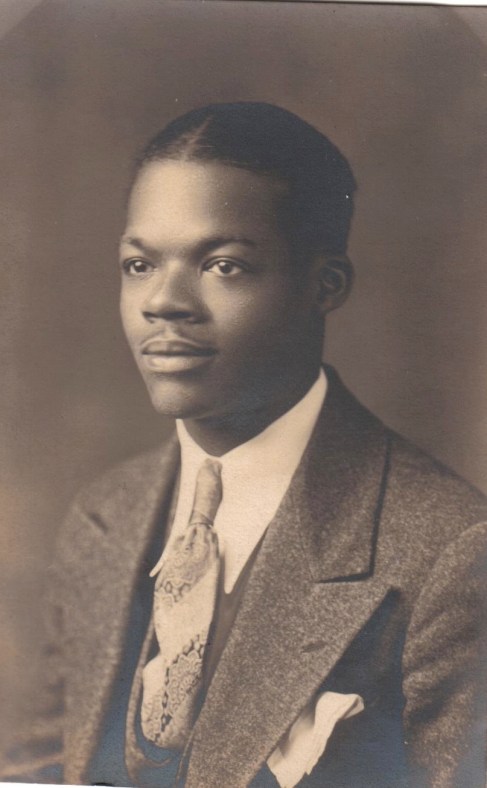

I happened upon this snippet unexpectedly while updating some old genealogy files. Stephen Whirley was the husband of Emma Allen Whirley, my great-grandfather John C. Allen Sr.’s sister. John Whirley was Emma’s step-son. John and Emma lost contact — intentionally? negligently? — when my grandfather was young, and no one in my family knows much about the Whirleys. However, thanks to the Baltimore Afro-American, now searchable via Google, my irrepressible almost-cousin John comes to life:

AFRO Goes Out On “Check Day”

Friday, Sept. 10, was Welfare Check Day in Baltimore.

That’s “Mother’s Day” when the money flows (“one great big bash”) and crime soars (“reaches its peak”), all according to Jerry Cartledge, author of the News American’s “Welfare Wastelands” series.

So absorbed was Cartledge with his “Mother’s Day” expose that he challenged one and all:

“Stroll down Dream Street (Pennsylvania Ave.) or Gay St. next Mother’s Day – if you don’t value your life – and see for yourself.”

Seven AFRO staffers decided if American reporters can risk their lives in such places as Vietnam, they could venture out on “Mother’s Day” in Baltimore.

They found the day and night like any other Friday or Saturday and concluded that much of the Mother’s Day piece was pure fantasy which appears questionable in so far as personnel [sic] observation and interview can determine – and that those charges that can checked by police or court records definitely are false.

The busy and dangerous places cited in the article include Pennsylvania, Fulton and Fremont Aves., Gay, Orleans and Madison Sts.; the Wagon Wheel, the Ubangi Club, the Sportsmen, “Della’s” and the Charleston.

The AFRO team hit them all – and some others – and still could not find justify charges that “Mother’s Day” is the worst every month.

…

Owners like Jack Roosevelt of the Sportsman, Bill Kramer of the Maryland Bar, and all the owners and operators contacted, laughed at claims they put in extra stocks for “Mother’s Day.”

John Whirley of the Ubangi Club said, “I never saw or talked to Cartledge. Nobody has been in here seeing the things in the article. Two or so welfare people might come in here. The receipts (on Mother’s Day) are the same as any other day without the checks.

“I know he’s lying. I wish he’d come around. Look around here. These are working people. That’s the kind of people I get, working people.”

… — Baltimore Afro-American, 14 Sep 1965.

and

Numbers Personalities Pay Fines of $8,500.

BALTIMORE. Appearing in Criminal Court this week were nearly two dozen numbers personalities who in 1968 were known to literally thousands of lottery players in all sections of the city.

In the group were nine defendants who paid a total of $8,750 in fines alone.

Two persons received jail sentences.

One defendant swallowed a numbers slip. Another drove his car in reverse up the street to avoid police and a veteran Avenue bar owner and a longtime South Baltimore real estate dealer pleaded guilty.

…

JOHN WHIRLEY.

Getting off lighter was another familiar Avenue figure, John Whirley, 70, owner of the 2200 block Pennsylvania Ave. Ubangi Bar.

Judge Sodaro suspended a prison sentence of three months and imposed a $250 fine and costs on the elderly man who pleaded guilty to lottery violations.

According to testimony before the court, Whirley was arrested in a Vice-Squad raid on his bar at 11:20 a.m., Nov. 25, 1968. An arresting officer said he found one slip indicating $2.50 in play wrapped in a roll of $55 cash in Whirley’s pocket. In the basement, according to testimony, there were two slips containing 15 numbers and $11.50 in play. — Baltimore Afro-American, 2 Aug 1969.

The Baltimore Afro-American, 26 December 1959.

The Baltimore Afro-American, 26 December 1959.