Happy 91st birthday to cousin Carrie Jo Augusta James Fane!

Tag Archives: Colvert

Aunt Mat and her children.

Mattie Colvert, oldest daughter of Lon and Josephine Dalton Colvert, was born in 1895 in Statesville, North Carolina. She married Charlie W. James in Statesville, North Carolina, in 1913. In the 1930s, Aunt Mat and her children migrated North to New York City, where this photo probably was taken.

Willis H. James, James E. James, Charles James, Mattie Colvert James, Carrie James James, Lon W. “Lawrence” James, John Bristol Clemons, and Shelton H. James.

Willis H. James, James E. James, Charles James, Mattie Colvert James, Carrie James James, Lon W. “Lawrence” James, John Bristol Clemons, and Shelton H. James.

Remembering Launie Mae Colvert Jones.

Grandma: Launie Mae was a mama’s baby.

Me: Aunt Launie Mae was a mama’s baby?

Grandma: Yes, Lord. [I laugh.] With all her soul.

——

My mother: I thought Aunt Launie Mae looked more like Grandma Carrie than anybody. She looked the most like of her all the sisters.

——

Remembering my great-aunt LAUNIE MAE COLVERT JONES (1910-1997) on her birthday.

Remembering Grandma Carrie.

Me: In her pictures she always looked stern.

My mother: Grandma?

Me: Carrie.

Ma: Grandma Carrie? I know it. But she was funny. She was funny to me. She could say some of the, she could say some funny stuff. I know that’s where Mama gets it from. The little sayings.

Statesville Landmark, 20 December 1957.

My grandmother didn’t think much of Charles V. Taylor:

Course she met this guy and married him that she had known him when she was a child. Taylor. And went to New Jersey. She came back home, and Mama had high blood pressure, you know. But she kept, her doctors kept it in check. But he hadn’t let her go to the doctor for two times, and she had a stroke and died. Oooo. I could have killed that man. I was so mad with that man I didn’t know what to do. And when we went down there, Mama just got worse and worse. She went to the hospital, and they did everything they could at the hospital, and then they let her come home. And I went down there to see her one time, while she was at home, you know, and she couldn’t talk. She couldn’t talk, I mean. And she would try her best to tell me something. And I just cried and cried and cried and cried and cried. And I didn’t know what she was trying to tell me. So my sister lived not far from her. And she was a cafeteria manager, but she would come to see Mama between the meals. You know, in the morning breakfast and lunch, and then after dinner she’d come. She really did take care of Mama when she was living with that Thing. And she went to the hospital and stayed awhile, and he wouldn’t pay the hospital bill. And I took a note out at the bank, and Louise paid her doctor’s bill and everything, and when she died, he tried to make us pay all the burial expenses. And his brother came over there and told us, said, “Don’t you pay a penny. ‘Cause he’s got money, and he’s supposed to use it for that.” And said, “Don’t you do it. Don’t you give it to him.” And that man and the undertaker got together and planned all that stuff against us, you know. The three of us. It was terrible. And Mama had a lot of beautiful clothes, you know, because this man bought her things. And they were all in there looking at them. I said, “I don’t want a thing. I don’t want not one thing.” I think I got a coat. It was just like a spring coat. It was lined. And I think Louise insisted that I take it, but that was the only thing that I took.

——

Remembering Caroline Martha Mary Fisher Valentine McNeely Colvert Taylor, who died 56 years ago today.

——

Interviews of my mother and Margaret C. Allen by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved.

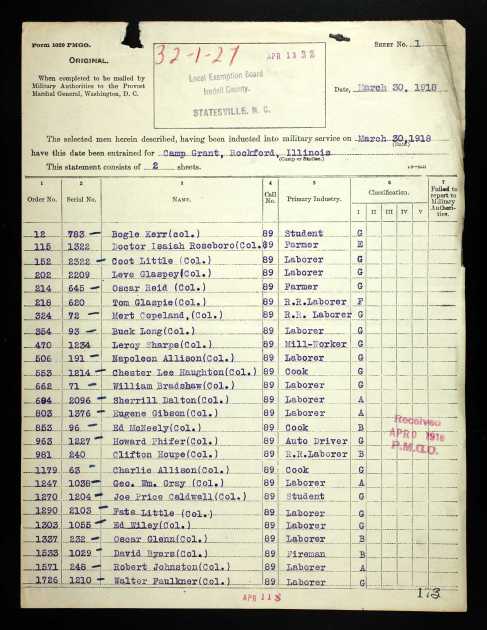

Ordered to report.

This roster of African-American men from Iredell County inducted on March 30, 1918, and ordered to report to Camp Grant, Rockford, Illinois, included my grandmother’s maternal uncle, Ed McNeely, and brother-in-law William Bradshaw. (Bradshaw married Golar Colvert eight days after his induction.)

[War Department, Office of the Provost Marshal General, Selective Service System, 1917– 07/15/1919. Lists of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Service, 1917–1918. Records of the Selective Service System (World War I), Record Group 163. National Archives, Atlanta, Georgia.]

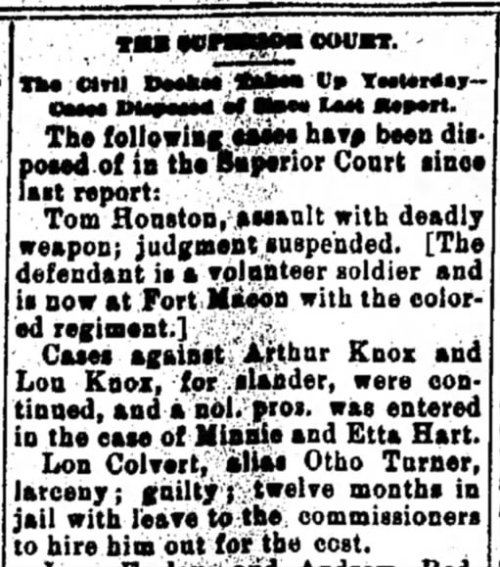

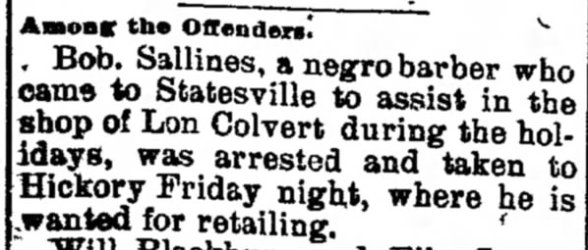

Lon Colvert: straight and shady.

If reports are to be believed, Lon Colvert had a bit of a shaky start. “Otho Turner”?

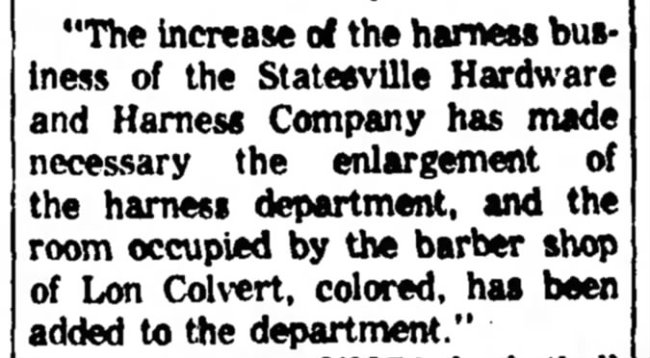

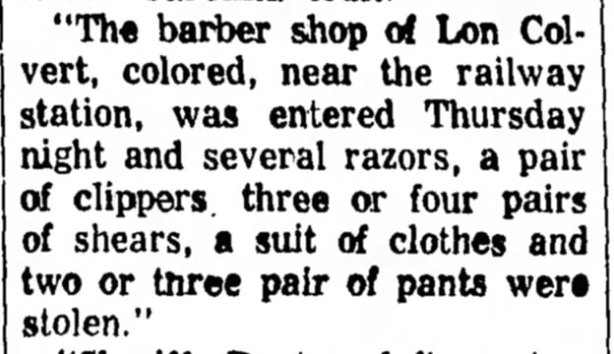

Statesville Landmark, 18 August 1898.

Statesville Carolina Mascot, 8 February 1900.

Lou Colvert was Lon’s uncle. No details on Lon packing. But he switched gears a bit. To retailing, which specifically meant selling liquor — unauthorized.

Iredell County Superior Court —

Lon Colvert, retailing; guilty.

— Statesville Landmark, 5 Nov 1901.

Another poor outcome.

“Cases Disposed of Since Monday — Some Recruits for the Chain Gang — A City Ordinance Held Invalid”

The following cases have been disposed of in the Superior Court since Monday: …

Lon Colvert, convicted of retailing, was discharged on payment of the costs.

— Statesville Landmark, 8 Nov 1901.

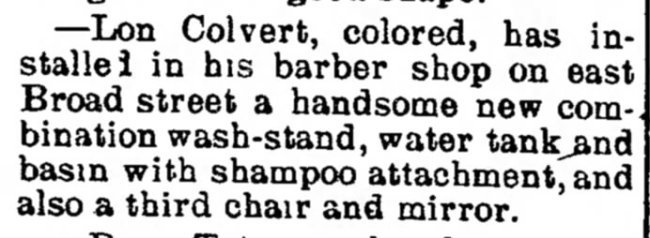

But somewhere along in here, he began to right his ship.

Notices of New Advertisements.

L.W. Colvert has moved his barber shop from Depot Hill to 109 east Broad street.

— Statesville Landmark, 23 Aug 1904.

It’s not clear when Lon first opened his barber shop, or how he got into the business, but it was a good move. Depot Hill was a few blocks south of downtown; the 100 block of East Broad was right at the heart of the business district. He had arrived.

Still, there were setbacks. (I read “liquor” in this “little pilgrimage,” but I could be wrong.)

“Played His Bondsman False and Will Spend his Holidays in Jail.”

Thursday afternoon a colored barber, Lon Colvert by name, braced Mr. J.P. Cathey for a horse and buggy with which to make a little pilgrimage that night, and Mr. Cathey refused. Lon was just obliged to make that little run, so later he stated the case to Jo. Thomas. Jo. is the colored individual who worked for Mr. Cathey then and who is now being boarded by the county. Jo. slipped out with a horse and buggy. Lon made his trip, came back, paid Jo. one plank, which he shoved down in his jeans, and then Jo. slept the sleep of the consciousless offender.

But the snow that fell during the interval between the exit and return of that buggy caused Jo’s little house of cards to tumble. Next morning Mr. Cathey saw the tracks, asked Jo. who had got a buggy the night before, and Jo straightaway told the thing that was not. So Mr. Cathey got off of Jo’s bond, which he had signed not long since, and now Jo. is behind bars.

— Statesville Landmark, 20 Dec 1904.

He pressed on.

Lon Colvert, colored, has recently equipped his barber shop on east Broad street with a handsome two-chair dressing case and has made other improvements in the shop.

— Statesville Landmark, 1 Jan 1907.

Statesville Landmark, 1 January 1907.

But he had a new wife and a new baby to add to his first three, and the straight and narrow was starting to win.

Statesville Landmark, 7 May 1907.

Statesville Landmark, 7 January 1910.

A momentary setback, no more. Lon moved his business back down Center Street toward the train depot and entered the golden age of his entrepreneurship, the period of my grandmother’s childhood.

Papa had a barber shop. Well, of course, Papa did white customers. And, see, the trains came through Statesville going west to Kentucky and Tennessee and Asheville and all through there. They came through, and they had, they would stop in Statesville to coal up and water up, you know. There were people there to fill up that thing in the back where the coal was. And there was another — it had great, big round things that they’d put in water. And when those trains would stop for refueling, they would, there were a couple of men who would come. I can see Walker and my uncle and Papa standing, waiting for these men who were on the train to give them a shave and get back on the train in time. And there wasn’t any need of anybody else coming in at that time ‘cause they couldn’t be waited on. They were waiting for these conductors and maybe mailmen, but I know there would be at least three at a time. And Papa would shave them. And he made a lot of money.

Papa had a taxi, too. Walker drove it most of the time. And then he would hire somebody to drive it other times. And then when people had to go to Wilkesboro, Papa would take them. Because Wilkesboro was a town north of Statesville. And there was no transportation out there. No buses, no trains, or anything. So when people would come on the train that were, what they call them, drummers, the salesmen, when they would come through, Papa would carry them up there.

And he had this clean-and-press in the back of the barbershop. And, look, had on the window, on the store, ‘Press Your Clothes While You Wait.’ I can see those letters on there right now. ‘Press Your Clothes While You Wait.’ And people would go in there, get their clothes pressed, you know. And I know ‘barber shop’ was on the door…. ‘L.W. Colvert Barber Shop.’ ‘L.W.’ was on the side of this door, and ‘Colvert’ was on this side of the door. They had a double door.

There were, of course, risks to doing business. Though I’m casting a side-eye at the carnie. (“H.G.” was Lon’s 21 year-old half-brother Golar, and I never knew he was a partner in the business.)

Damages for Scorching Suit — Court Cases.

Lon Colvert and H.G. Tomlin, doing a pressing club business under the name of Colvert & Tomlin, were before Justice Sloan Saturday in a case in which Chas. Moore, white, a member of the carnival, was asking $18 damage for them. They pressed a suit for Moore and it was scorched, for which Moore asked damage. The case was finally compromised by Colvert & Tomlin paying Moore $5 and $1.20 cost.

— Statesville Landmark, 27 March 1917.

And there was the little matter of a charge of carrying a concealed weapon in 1919; a jury returned a not guilty verdict. Still, a burglary at the shop was an omen. The good years were coming to an end. Lon was struck with encephalitis in the 1920s and was largely unable to work in his final years.

Statesville Landmark, 25 September 1925.

By this time, Golda had embarked upon a peripatetic life in the Ohio Valley, and Walker was left to keep his father’s businesses running. He exercised his best judgment.

Walker Colvert, driver of the Wilkesboro jitney Steve Herman, driver of the Charlotte jitney, and Henry Metlock, driver of the Taylorsville jitney were charged with delivering passengers to the depot rather than the jitney station. It appearing that all the violations were emergency calls, the defendants were discharged.

— Statesville Landmark, 1 Mar 1926.

Lon Colvert died 23 October 1930. “He was an old resident of Statesville,” his obituary noted, “and for a number of years had a barbershop on South Center street, near the Southern station.”

The barbershop, 1918, when it was at 101 South Center Street. Walker Colvert, center, and L.W. Colvert, right.

The barbershop, 1918, when it was at 101 South Center Street. Walker Colvert, center, and L.W. Colvert, right.

——

Interview of Margaret C. Allen by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved. Copy of photograph in possession of Lisa Y. Henderson.

There she is.

There she is. That’s one of those dresses that Mama made for her to come to Hampton. She came to Hampton a summer. She stayed more than six weeks. Must have stayed around eight or ten. But anyway, she came here, and the things that she learned! Oh, you would not believe. All kind of things – artwork she could do. Making baskets. Oh, I don’t know what all. That’s a blue taffeta dress with a white collar. And you know we had a supervisor [Mary Charlton Holliday] who came to Statesville, and she particularly liked Golar, and she was a Hampton graduate, and she wanted Golar to go to Hampton so she could learn all this stuff. All this artwork and everything. And when she got ready, when Golar got ready to go, Mama had bought – this is a navy taffeta dress with a white collar. And Mama had made all these dresses for her. She had – this was a dressy dress. And she had a pink dress, and she just, Mama just made her so many pretty things, you know. And the, two or three nights before she was to go, to leave to go to Hampton, she broke down and cried. Mama said, “What’s wrong?” Said, “We’re gonna be, we’re gonna have your things ready. You’re gonna be ready to go.” And she said, “That’s not why I’m crying.” She said, “I’m crying because Papa and Grandmama went to the bank and took out all of your money.” Mama had paid into her Christmas savings account, and the bank just gave the money to Grandma and Papa, and that’s how they got her things together. And she told Mama. Ooooo.

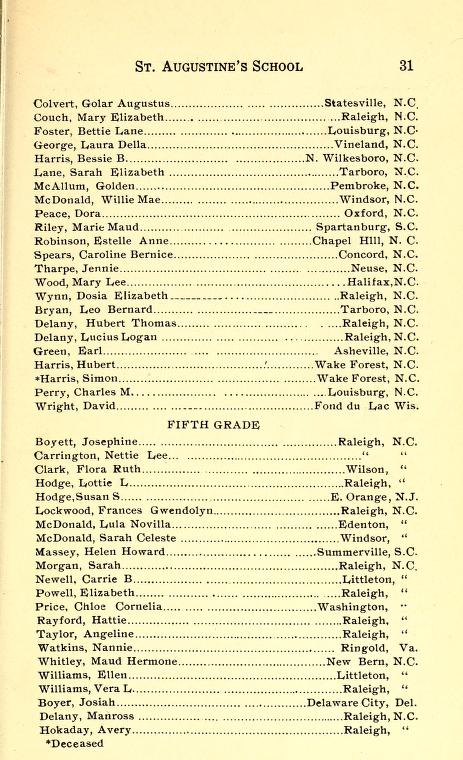

Golar Augusta Colvert was born in 1897 in Statesville, Iredell County, to Lon W. Colvert and his first wife, Josephine Dalton Colvert. She was about 9 years old when her widowed father married Carrie McNeely, and she grew close to her stepmother and adoring young half-siblings. When she was about 15, she enrolled at Saint Augustine’s College in Raleigh NC, where school catalogs show that she was a classmate of the Delany Sisters’ younger brothers.

Annual Catalog of Saint Augustine’s School, 1913-1914.

In 1919, Golar married William Bradshaw, son of Guy and Josephine Bradshaw. Their son William Colvert Bradshaw was born in 1921 and daughter Frances Josephine in 1924. The little girl did not live to see two years. William worked in a furniture factory and Golar taught elementary school, and the family lived in a large frame house with a wrap-around porch on Washington Street in Statesville’s Wallacetown section.

In the summer of 1931, for reasons that are not at all clear, Golar traveled to Washington DC to undergo surgery.

Yeahhhh. Went to Washington. Had this operation and, ah, we got a letter from her. Like, this afternoon, saying that she was all right, that they were gon take her stitches out, and she was coming home. And she died that night.

Statesville Landmark, 23 July 1931.

Statesville Landmark, 27 July 1931.

Interview of Margaret C. Allen by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved.

Lon W. Colvert.

Lon W. Colvert was born 10 June 1875 to Harriet Nicholson and John W. Colvert. He possibly was their second child and certainly was the only one to reach adulthood. My grandmother emphatically stated that his middle name was Walter, but her sister Launie Mae thought “Walker” – after his grandfather – and that’s the name that appears on certain records. Lon’s paternal grandparents reared him, but he was extremely close to his mother as an adult.

Lon was probably in his late teens when he arrived in Statesville from his family’s farm in the northern reaches of Iredell County. He was an ambitious young man with an eye on the main chance and a penchant for the shady that followed him even into his respectable years. By time he was 30, he was well-established downtown as a first-class barber, and the local paper obliged him with recognition:

Statesville Landmark, 7 May 1907

Statesville Landmark, 7 May 1907

Lon and his first wife, Josephine Dalton, had three children, Mattie (1895), Golar Augusta (1897) and John Walker II (1898). Soon after Josephine’s death, he married Caroline M.M.F.V. McNeely and fathered three more daughters, Mary Louise (1906), Margaret Beulah (1908) and Launie Mae (1910).

In the mid-1920s, Lon’s business successes were short-circuited when his health began to fail. He passed away 23 October 1930, 83 years ago today.

Lon Walker Colvert Dies in Wallacetown.

Lon Walker Colvert, colored, 55 years old, died this morning at 1 o’clock at the home of his daughter, Gola Bradshaw, in Wallacetown. He was an old resident of Statesville, and for a number of years had a barbershop on South Center street, near the Southern station.

The funeral service will be Friday at 2:30, at Center Street A.M.E. Zion church, with interment in the local cemetery.

Surviving are his wife and six children; also one brother and one sister.

— Statesville Landmark, 23 Oct 1930.

Possums and sweet potatoes.

My grandmother: His mother used to cook possum.

Me: Used to cook possum?

My grandmother: Oh, possum, honey. They would cook those dern things.

Me: Well, possum stew. I guess I have heard of that.

My grandmother: Naw. They didn’t have no possum stew. They’d bake this thing.

Me: Awwww!

My grandmother: And, look, wait a minute. You know they’ve got big mouths. Long mouths. A possum. And he’d put a sweet potato in the possum’s mouth. [I laugh, hard.] I don’t remember cooking one, but my grandmother sure used to cook ‘em. And Papa cooked ‘em. But I refused to cook ‘em. Not me. And you know these people when I came here ate muskrats?!

It was Harriet Nicholson Hart who fixed such special dishes for her favorite son.

Interview of Margaret C. Allen by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved.

She was smart, and she was musical.

FINALS AT COLORED SCHOOL.

Statesville Colored Graded School Closed Tuesday Night with a Very Creditable Performance.

The closing exercises of the Statesville graded school were held Tuesday night in the new building. Before the exercises began at 8.30, a representative of this paper had the pleasure of looking thru the building and inspecting the most creditable exhibits of the work accomplished by the pupils of the second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh grades. The exhibit showed surprising skill in drawing, sewing, fancy needle work and other forms of handiwork.

When the exercises began, the auditorium and two adjoining school rooms were filled, and the good order maintained was a noticeable feature. The opening chorus and duet by members of the graduating class were much appreciated by the audience.

“Resolved: That girls are more expensive to raise than boys,” was the subject of the debate discussed in an interesting manner by Eugene Harris and Harry Chambers, on the affirmative, and Guy B.Golden and Jettie M. Davidson, on the negative.

GRADUATING EXERCISES.

Class History. Buster B. Leach

Class Prophecy. Annie B. Headen

Class Poem. Willie D. Spann

Solo — ‘Be Still, O Heart.’ Thomas R. Hampton

Class Will. Maurie Dobbins

Valedictory. Louise Colvert

Class Song – ‘Fealty’

CLASS ROLL.

Mary Louise Colvert, Maurie Catherine Dobbins, Lillian Gennetta Moore, Willie DeEtte Spann, Buster Brown Leach, Annie Bell Headen, Thomas Richard Hampton, Eloise Earnestine Bailey.

Class Motto – We Learn Not for School, But for Life.

The colored people of Statesville take great pride in their school. They have a modern school building, steam heated and supplied with the latest equipment, something which very few towns and cities of the State have provided for its colored population. C.W. Foushee, the principal, has proven himself to be a good school man. He is assisted by eight teachers.

— Statesville The Landmark, 7 June 1923.

Louise went up to New Jersey and finished high school. They didn’t have a black high school in Statesville. They just had tenth grade. And she went to Jersey and finished high school in Jersey and then took a course in teacher’s education somewhere. I don’t know whether it was Winston-Salem or Salisbury. And then she taught at – Louise played an organ, I mean, she could play the piano. Yeah, she was just as smart as she could be. And she not only could teach, but she was musical. And she had heard she could get a job anywhere because she could do that. And I know Golar used to teach school, but Louise would do her commencement exercise for her. She would, Louise would do that, and they would have concerts. Not concerts, but the whole county would compete. And Golar’s thing would always bring a group of children, ‘cause Louise would teach them, you know. I don’t know, I can’t remember the name of that place. But she had a school out there. Williams Grove. And Louise used to do all the playing for that school, and they would ask her to prepare them for the thing. They had these county somethings. But it involved the whole county. The schools were all over Iredell County. And they would come together, and they would, it would be a big march, and then they would meet somewhere in particular, and then they would compete with the groups of singers and everything like that. And, child, when Louise started that stuff, when she started teaching, she had groups singing – young people and the older people, and then Golar would take her to her school and get her to teach her children.

Interview of Margaret C. Allen by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved. Photographs in the collection of Lisa Y. Henderson.