I give and bequeath to my beloved son Thomas A. the following Negroes to wit Carlos Nelson Lucinda and Joe.

——

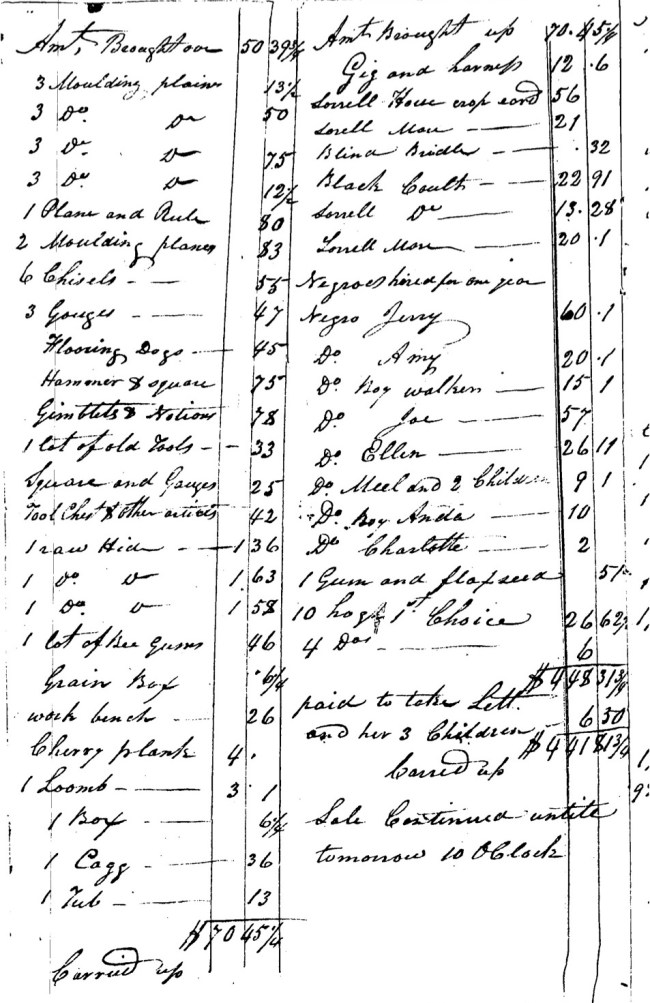

On 19 Nov 1850, James Nicholson wrote out his last will and testament. Two days later, before he could sign it, he slipped into death. The document was registered 19 Jun 1852 in Will Book 4, page 666 at the Iredell County Register of Deeds Office. Nicholson’s only heirs were his widow Mary Allison Nicholson and sons Thomas A. and John M. Nicholson. James left Thomas 185 acres and John 242 acres and gave them a 75-acre mill tract in common. Mary Nicholson received slaves Milas, Dinah, Jack, Liza and Peter; John received slaves Elix, Paris and Daniel; and Thomas received the four named above. In addition, James bequeathed Thomas and John slaves Manoe, Armstrong, Manless, Calvin and Soffie jointly.

Thomas A. Nicholson put Lucinda to work in his home preparing meals and otherwise caring for his family. As Thomas’ son James Lee Nicholson grew to adulthood, he took increasing notice of the woman who cooked his suppers, laundered his shirts and emptied his slops. In 1861, she gave birth to his first child, a daughter that she named Harriet Nicholson. Lucinda and Harriet remained in Thomas Nicholson’s household till Emancipation, when they were provided with a small house and other support.

As the story goes, Harriet did not learn her father’s identity until her mother Lucinda revealed it on her deathbed. Lee Nicholson passed away when Harriet was 10 years old, leaving a widow and two small boys. Lucinda may have died even earlier, as she has not been found in the 1870 census. She had one other child, a son named William H. Nicholson, whose father was Burwell Carson. Based on information supplied by Harriet, William’s death certificate lists Lucinda’s maiden name as Cowles. We know nothing else about her life.