Her headstone is wrong. Mary Agnes Holmes was born October 15, 1877 — not October 22 — on the R.L. Adams’ plantation in Charles City County, Virginia. Her parents were tenant farmers there, and Agnes was one of a handful of Jasper and Matilda Holmes‘ children to survive to adulthood.

Agnes’ mother died when she was about 8 years old, and her father apparently did not remarry. Jasper Holmes was an ambitious man and managed to purchase several small plots of farmland upon which he supported his family in a degree of comfort. The Holmeses may have attended New Vine Baptist Church and, if so, that is likely where Agnes met John C. Allen.

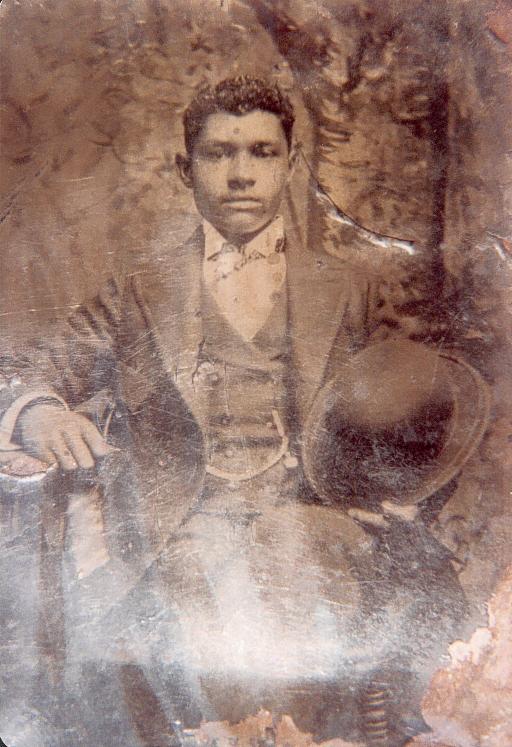

There is an ugly story told about their marriage: John had quickly established himself as an eligible bachelor in Newport News’ East End, and his appeal was heightened — in the standards of the day — by his light skin and wavy hair. When he brought his new bride home shortly after Christmas 1900, his neighbors, peeking through curtains, were shocked to see a plain, broad-featured, brown-skinned woman step from the carriage. (Agnes herself was not immune to such prejudices, and her color-struck notions would reverberate among her offspring.)

During the early years of her marriage, Agnes did “day’s work” as a housemaid. I did not know this. I had assumed that she was always a housewife, which is a reflection of my failure to understand just how my great-grandparents were able to achieve the middle-class respectability that marked their lives by the middle of the 20th century. (Not to mention how they maintained their dignity on the climb.)

Me: Now, his mama didn’t ever work, did she?

My grandmother: Who? Indeed, she did work.

Me: Like, outside the home?

My grandmother: Yeah, during the late years, she didn’t, but she worked outside the home ‘cause she told me one time she walked across the bridge, ‘cross 25th Street bridge, and said it was snowing and ice, and the ice froze on the front of her coat. And I never shall forget, she worked for a lady, and this lady had a small child. And she asked her would she wash the child’s sweaters. Sweaters that the baby had. And she took and said, “Asking me to do all kinds of extra work like that,” and said, “You know what I did?” Said, “I washed the sweater in hot water, and then I put it in cold water. When I got through with it, it was ‘bout big as my fist.” I said, “How can [whispering, inaudible.]” And she knew it –

Cousin N: Was gon shrink up.

My grandmother: And I said, “Oh, my God, that is awful!” And it was. Anyway, she told me that. She said, “I washed it all right for her, and I put it in hot water, as hot as I could find, and then put it in cold water. When I got through with it, couldn’t nothing wear it.”

By the time my mother and her siblings were children, Mary Agnes Allen had assumed the domestic role I’d always imagined her in — at home on Marshall Avenue, among Tiffany lamps and lace antimacassars, preparing roast beef to serve on Blue Willow china to a husband just home from this board meeting or that union affair. Her grandchildren speak of her ambivalently, aware of the casually cruel distinctions she drew among them, but unable to name any particular misdeed.

Me: Well, was Mary Agnes mean to y’all or what?

My mother: She was not to me, that I remember. I don’t know what this was about. Ahh … maybe it was that she was not friendly. Maybe she wont like Grandma Carrie, joking and saying little funny stuff. I don’t know. I don’t know what it was.

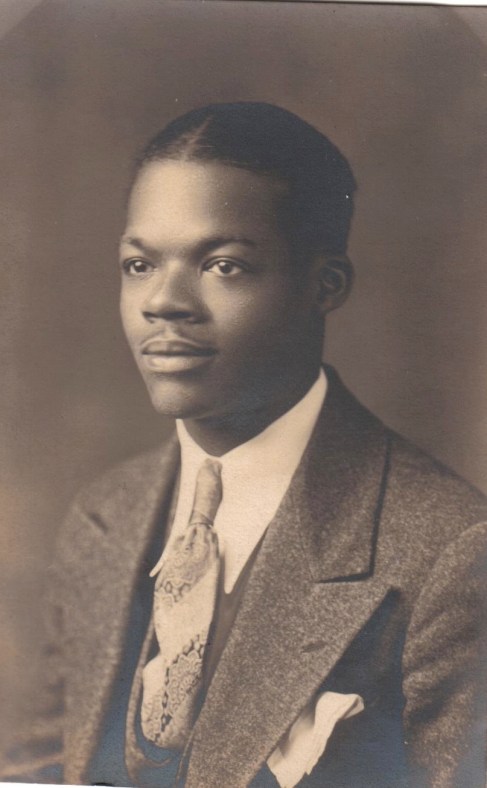

Her grandchildren — at least, her son John’s offspring — felt that lack of warmth acutely. Though their 35th Street home was only a mile away from hers, Mary Agnes Allen does not feature much in the stories of their childhood. (Nor, frankly, does John Allen Sr.) In her later years, she left Newport News to live with her daughter Edith Allen Anderson in Jetersville, Amelia County, Virginia. The photo below, I’m guessing, was taken shortly before her move. And seems to reveal a softer side.

Mary Agnes Holmes Allen died March 15, 1961, just two months before my mother married in the sideyard at Marshall Avenue. A brief obituary ran in the Daily Press on the 17th, noting that she was a member of Armenia Tent No. 104 and the Court of Calanthe. She was survived by three daughters, a son, a “foster son” (actually, her nephew), a sister, and, most curiously, “12 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren.” In fact, she had ten grands and no more than three great-grands.

Interviews by Lisa Y. Henderson, all rights reserved. Photographs in collection of Lisa Y. Henderson.