Mt. Ulla.

A meeting of the friends of prohibition was held at Wood Grove, Mt. Ulla Township, on the 4th instant. W.L. Kistler. Esq., was called to the chair and Rev. J. G. Murray, col. was elected secretary. The object of the meeting was explained by Dr. S.W. Eaton. The following resolution was offered by J.T. Ray and unanimously adopted after appropriate remarks from Rev. J.G. Murray and other.

Whereas, In consideration of the evil of Intemperance, caused by the sale and use of intoxicating liquors upon society, which promotes crime and other known vices, and thereby increasing taxation upon the citizens for the suppression, and also entailing injury in some or other upon all classes and conditions of our fellow men, Therefore

Resolved, That we do hereby heartily approve of the action of our County Commissioners in refusing to grant license for the retailing of intoxicating liquors to be used as a beverage in Rowan County.

Upon motion the chairman and secretary were requested to appoint a committee for permanent organization to meet on Saturday the 11th inst., at 3 o’clock, P.M.

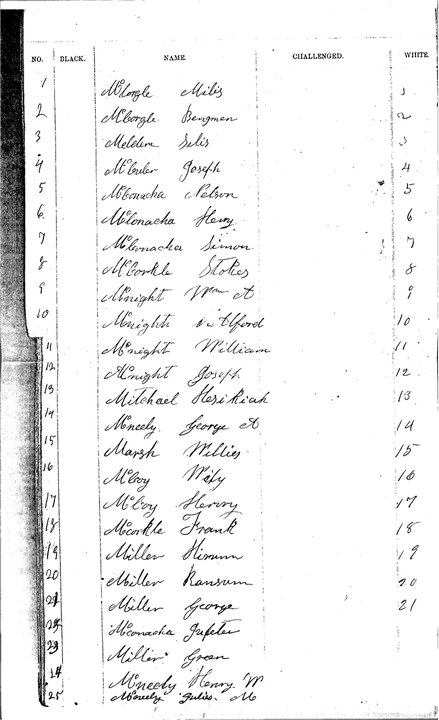

The committee for permanent organization are as follows: White – S.A. Lowrance, D.M. Barrier, J.C. Gillespie, J.T. Ray, J.K. Goodman, S.C. Rankin, S.F. Cowan, J.M. Harrison, M.A. File, R. Lyerly, J.K. Graham, Esq. Colered – W.W. Kilpatrick, Ransom Miller, Henry McNeely, Andy Gillespie, Amos Foster, George Miller, R.A. Kerr, James Rankin, Julius McNeely, Silas Gillespie, Gabriel Kerr.

Upon motion the meeting adjourned to meet on Saturday the 11th inst., at 3 o’clock, P.M. W.L. KISTLER, Ch’m. J.G. MURRAY, Sec.

The Carolina Watchman, Salisbury NC, 9 June 1881.

Wood Grove, Rowan County, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Wood Grove, Rowan County, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

——

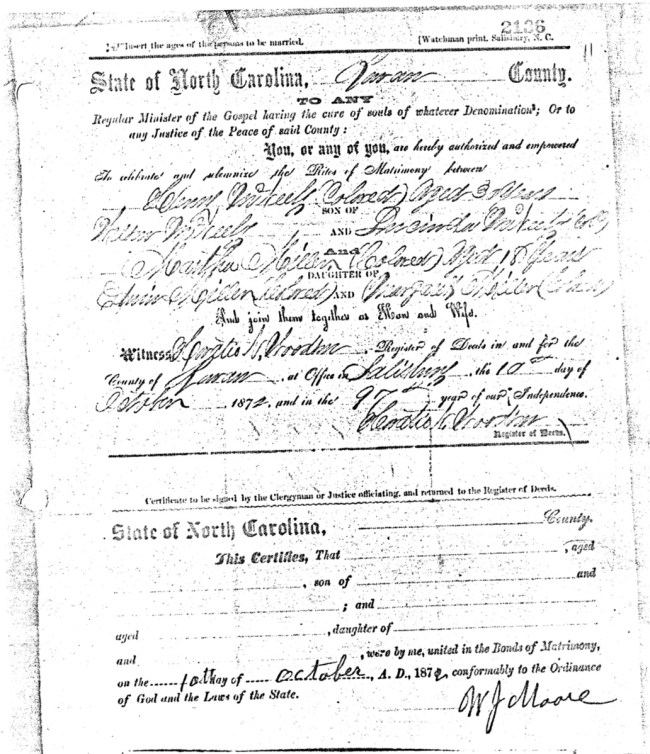

Henry McNeely and his half-brother Julius McNeely were joined on the committee by Henry’s brother-in-law George Miller and his wife Martha’s brother-in-law Ransom Miller.

Half-way across the country, in Iron County, Missouri, William B. McNeely had not waited for the war to end and beat his brother to the punch by nine months.

Half-way across the country, in Iron County, Missouri, William B. McNeely had not waited for the war to end and beat his brother to the punch by nine months.