She wanted a baby badly.

My grandmother: … that nephew, Dr. Lord’s son, that was Mr. Hart’s nephew. He got what Bert had. Yes, indeed. ‘Cause, see, it was heir property. And see that’s why Bert tried so hard to have a child. Because if she didn’t have a child, it was going to whoever had had a child. You know. And I guess Alonzo did, you know, he was a nephew. When Bert died, it went to him. See, all this property and everything that Mr. Hart owned there was his family’s stuff. Wasn’t Grandma Hart’s.

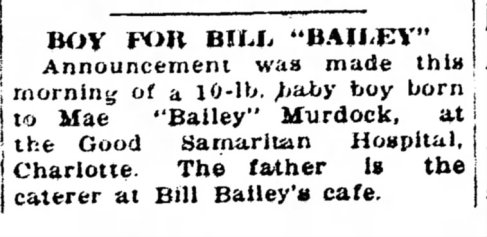

And in 1941, when she nearly 40 years old, Bertha Hart Murdock had one:

Statesville Landmark, 2 April 1941.

But little William Alonzo Murdock died the day after he was born.

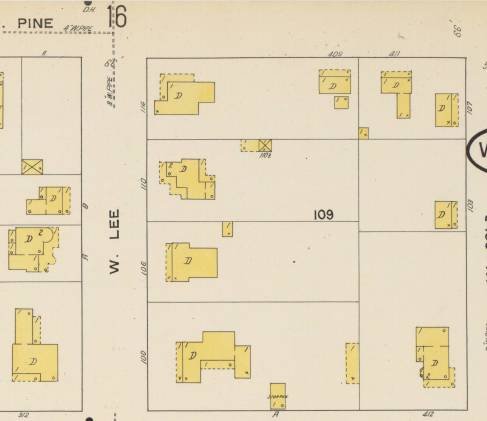

Still, the situation for Bert and her property was not as critical as my grandmother had believed. In Alonzo Hart’s original will, made 15 October 1928 in Statesville, he devised “the home place to my daughter Bertha Mae Hart and her bodily heirs, for ever, never to be sold and if she dies without bodilies heirs. Then it must be in trust for my sisters heirs to hold but never sell same.” The remainder of his property went to his sisters’ heirs.

Thirteen months later, as he languished in the state sanitorium in Quewhiffle, dying of tuberculosis, Hart dictated a codicil. In somewhat opaque and ungrammatical phrasing, Hart “hereby enlarge[d] the privilege to and use at her own and released to her. In stead of one parcel or tract of land I do bequeath and devise to her following described lands, In Iredell North Carolina, 45 acres in Concord Township (Deatonsville) Also 2 lots with one house Statesville Township also 47 acres in Shiloh township and Crawford near Sumters place 22 acres in above township near home belong to the home resdue. I am in my right presence of mind and know what is best for my only and legal heir Bertha Mae Hart.”

In other words, Bertha’s inheritance was generous and unrestricted, and her cousin Alonzo Lord was not to receive anything at all. Things did not go smoothly, however. Hart’s unconventional wording opened the door to challenge, and Bertha was forced to defend her title.

Statesville Landmark, 21 November 1935.

Incredibly, this case went to the North Carolina Supreme Court: Murdock v. Deal, 208 N.C. 754, 756, 182 S.E. 466, 467 (1935).

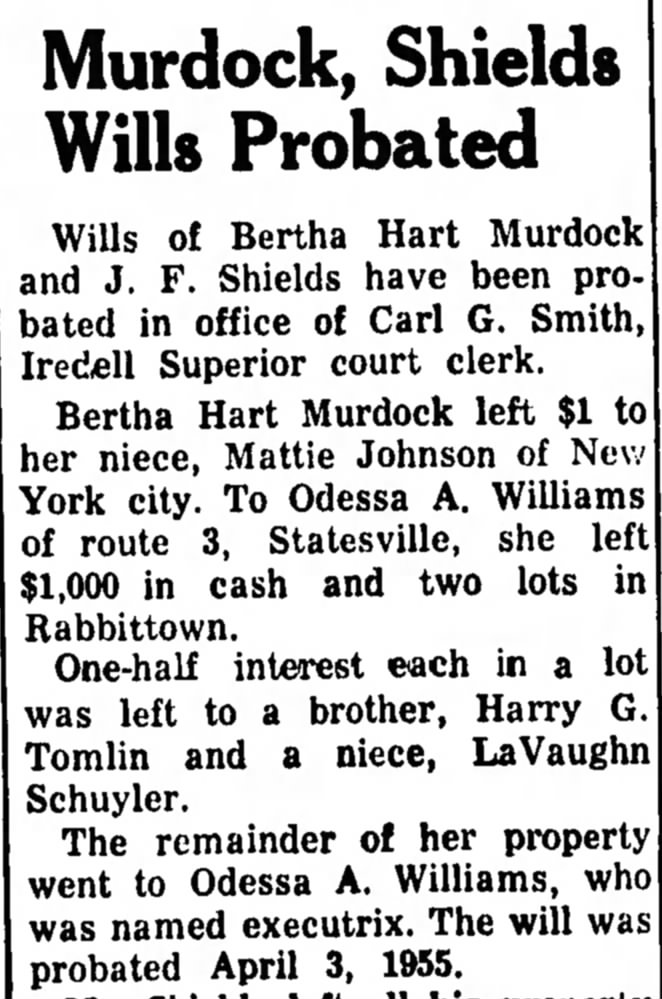

By time Bertha died in 1955, her estate seems to have been much reduced, but still comprised some of Alonzo Hart’s land. The bulk of her estate went to Odessa A. Williams, who may have been her cousin. Her half-brother H. Golar Tomlin inherited only a half-interest in a lot. His daughter Annie LaVaughn Tomlin Schuyler received the other half. Another niece, Mattie Johnson, received the negligible sum of one dollar, which raises questions: who in the world was she? I only know of Golda’s one child. Was this in fact Mattie James, oldest daughter of Bert’s other half-brother, Lon Colvert? Why bother with a dollar? And why not give the other nieces, Louise Colvert Renwick, Margaret Colvert Allen, and Launie Colvert Jones, their own dollars?

Statesville Landmark, 8 June 1955.

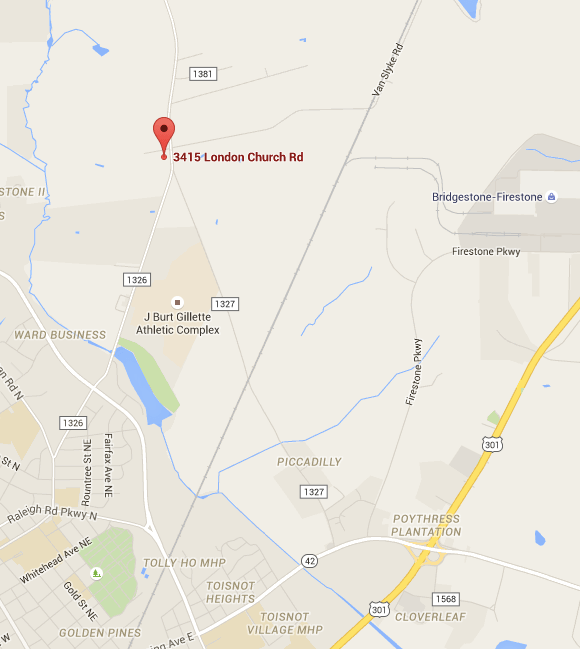

The drama did not end with Bert’s death. In what looks to be the family’s own Bleak House saga, City of Statesville v. Credit and Loan Company, a corporation of the State of North Carolina; W.S. Nicholson and spouse, if any, and if they be deceased, then their unknown heirs, and if any of said unknown heirs be deceased, then their respective heirs, devisees, assignees, and spouses, if any; and the unknown heirs of Minnie Brawley, Florence Camp, Mollie Alexander, and Lula H. Lord, Deceased, and if any of said unknown heirs be deceased, then their respective heirs, devisees, assignees, and spouses, if any; and all other persons, firms and corporations who now have, or may hereafter have, and right title, claim or interest, in the real estate described herein, whether sane or insane, adult or minor, in esse, or in ventre sa mere, active corporations or dissolved corporations, foreign or domestic, 294 S.E.2nd 405, was not decided in the North Carolina Court of Appeals until 1982.

The first sentence of the decision: “The sole issue is whether plaintiff has a valid avigation easement over land owned by defendant.” An avigation easement is a property right acquired from a landowner for the use of air space above a specified height. Alonzo Hart’s home property was located a few miles west of Statesville, adjacent to land now home to Statesville Regional Airport. (Brawley, Camp, Alexander and Lord were his sisters.) The City of Statesville’s claim that it held prescriptive easements was rejected, and partial summary judgment entered for the defendants.

——

Interview of Margaret C. Allen by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved.