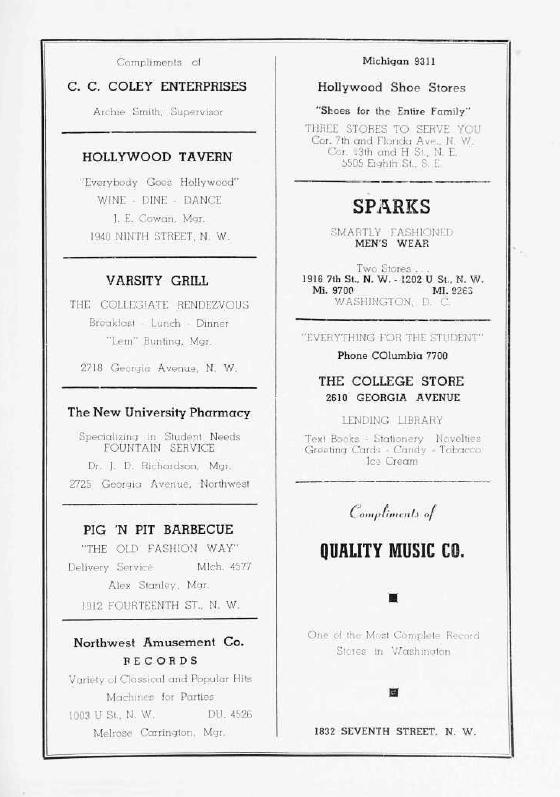

I was running some random Google searches when I ran across this Howard University yearbook entry. Charles C. Coley, class of 1930, was the son of Mack D. and Hattie Wynn Coley, grandson of Frances Aldridge Wynn, and great-grandson of J. Matthew Aldridge.

In the 1910 census of Brogden township, Wayne County: school teacher and widower Mack D. Coley, 45, and children Blonnie B., 12, Blanche U., 10, Charlie C., 7, and Rosevelt, 5, and great-aunt Kattie, 74.

In the 1920 census of Mount Olive, Brodgen township, Wayne County: on Rail Road Street, teacher Mack D. Coley, 54; wife Lillie, 40, teacher; and children Blonnie, 22, teacher; Blanche, 20; Charley, 17; Rosevelt, 15; and Harold, 2.

In the 1930 census of Washington, D.C.: at 70 Que Street, Northwest, Charles Coley, 26, and wife Harriett, 20, lodgers in the household of Oscar J. Murchison. Charles worked as a lunchroom waiter. Harriett was a native of Hawaii. They divorced before long, and Charles married Frances Elizabeth Masciana (1920-2010), the District-born daughter of an Italian immigrant father and an Italian-African American mother.

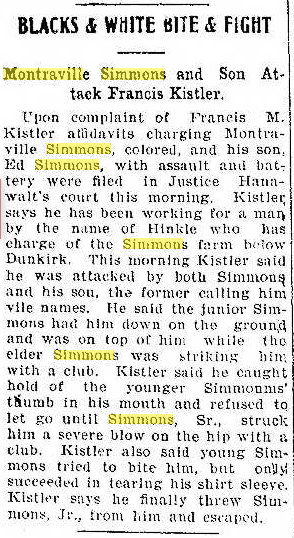

During the 1930s, Great Depression be damned, Coley began to build his entertainment and culinary empires, which eventually came together under C.C. Coley Enterprises, headquartered on U Street, D.C.’s Black Broadway. He rented jukeboxes to establishments across the city and owned several barbecue restaurants and other businesses in Northwest D.C. (More than a few Wayne County home folk newly arrived to the District got jobs working in Coley businesses.) On 16 December 1939, the Pittsburgh Courier screamed “Charge ‘Sabotage’ in Music Box Scandal” over a story whose heading was longer than its column inches.

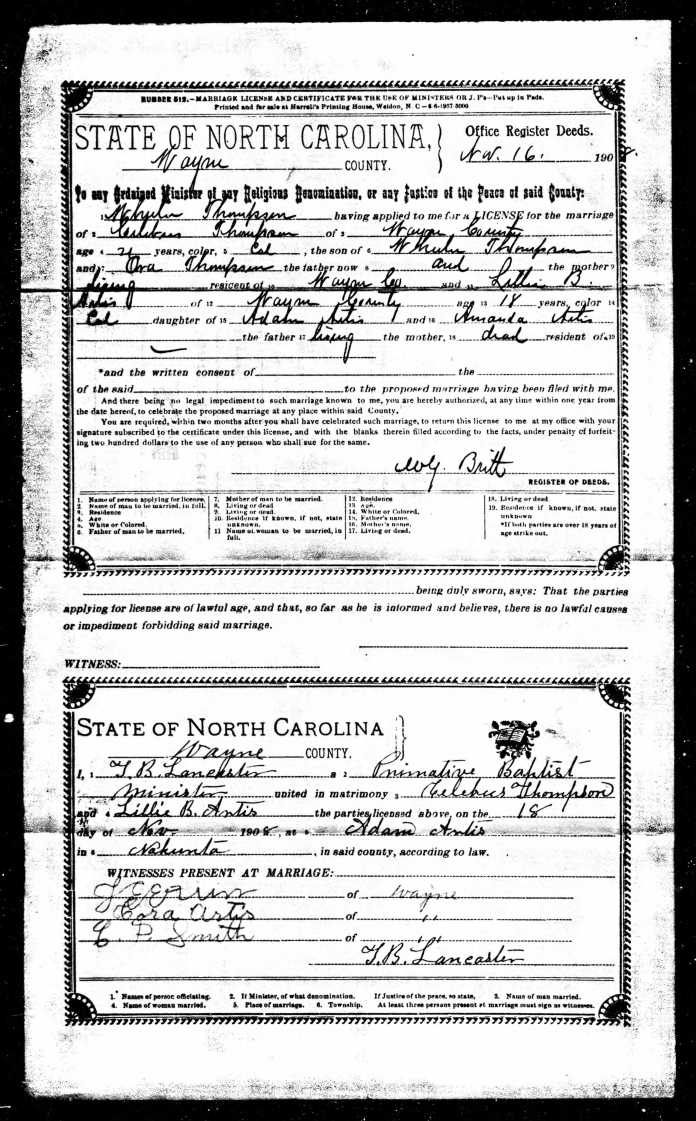

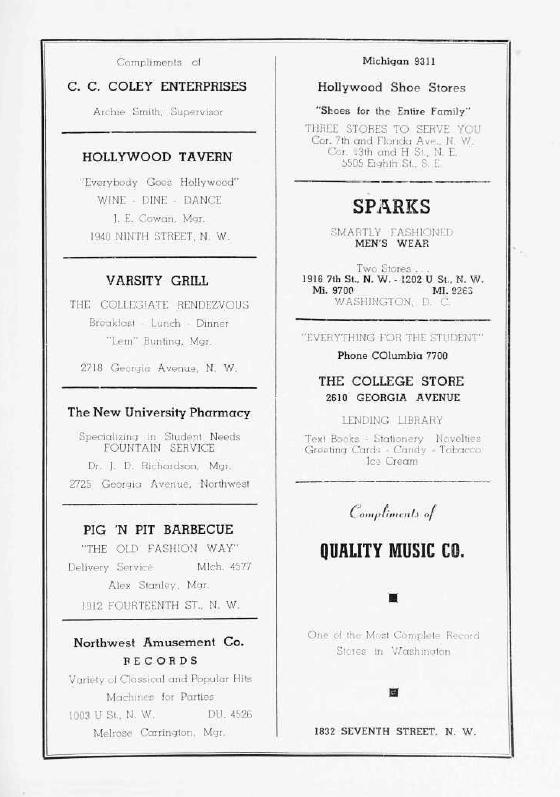

Coley was unfazed by this dust-up. In 1942, he was able to place an ad in Howard University’s yearbook touting several of his enterprises, the Hollywood Tavern, the Varsity Grill, the New University Pharmacy, the Pig ‘N Pit, and Northwest Amusement Company Records.

In 1942, C.C. put his financial weight behind the Capital Classic, an early fall match-up between black college football teams that anchored black D.C.’s fall social calendar. The Washington Post, in articles published 30 October 1980 and 9 September 1994, described the Classic’s genesis this way:

“Begun in 1942 by now-retired businessmen Charles C. Coley, Jerry Coward and Jessie Dedman, who were later joined by attorney Ernest C. Dickson, the Classic was a black business community extravaganza. From their offices on then fashionable U Street, the entrepreneurs founded the Capital Classic, Ltd. company to lure the interest and dollars of D.C.’s thousands of “colored” fans away from the professional teams which wouldn’t employ or seat blacks properly, and return those dollars to the black college teams.”

“The Classic offered the community, according to one of the printed programs, ‘. . . a massive arena where the radiant beauty of Negro women, who for so long, where beauty is concerned, have been in the shadows — shaded by the accepted Nordic ideal can move proudly to stage center and radiate the bronze charm that will always be the heritage of women of color.'”

Coley was also an early civil rights activist. His financial backing enabled trailblazer Hal Jackson break into D.C. radio, and an op-ed piece in the 14 April 1943 edition of the Pittsburgh Courier gave details of more direct action. Angered by the difficulty he had catching cabs in Washington, Coley contacted the Urban League with a proposal. He would pay the salary for a man to work full-time tracking instances of discrimination by cabbies. “Mr. Coley has these taxicab drivers who pass up passengers, white or colored, at the Union Station or anywhere else in the city, fighting for their licenses.” The city’s Public Utilities Commission was shamed into putting its own spotters on the street. “Discrimination is being met a knockout blow — not by what Mr. Coley said, but what he did. … This story is … being passed along for the benefit of some Negroes who, in similar situations, never think of putting their money where their mouth is.”

Baltimore Afro-American, 13 November 1948.

Despite the photo op above, the Classic soon met difficulties behind-scenes. Coley withdrew temporarily from active promotion in 1945, and Dr. Napoleon Rivers replaced him as guarantor. Quickly, according to a federal lawsuit, Rivers began to “usurp control” and failed to pay Coley’s partners their shares. In ’47, he even set up a rival match — the National Classic — at Griffin Stadium. (For details, see the 23 October 1948 edition of the New York Age. The National Classic, by the way, moved to Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1954 and morphed into the C.I.A.A. football championship game. See the Pittsburgh Courier, 23 October 1954.) The Classic recovered and prospered until fading away in the 1960s.

Charles C. Coley died 11 April 1986 in Washington, D.C. He is buried in Rock Creek Cemetery.

C.C. Coley’s Pig ‘N Pit Restaurant at 6th and Florida Avenue, Washington DC. This undated Scurlock Studios image is found in Box 618.04.75, Scurlock Studio Records, ca. 1905-1994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.