I’ve written here and here about the migration of Adam T. Artis‘ children Gus K. and Eliza to Arkansas. Though most of his 30 or so children remained in North Carolina, a few went in North. Or, at least, a little further north. One was Haywood Artis, born about 1870 to Adam and his wife Frances Seaberry Artis. He was my great-great-grandmother Vicey‘s full brother.

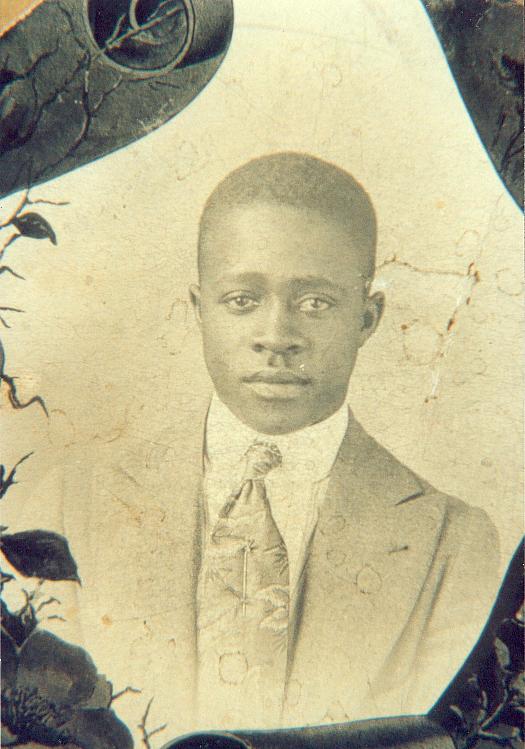

Haywood Artis

In the 1880 census of Nahunta, township, Wayne County, North Carolina, Adam Artis, widowed mulatto farmer, is listed with children Eliza, Dock, George Anner, Adam, Hayward, Emma, Walter, William, and Jesse, and four month-old grandson Frank Artis. (I’ve never been able to determine whose child Frank is.]

Haywood’s whereabouts over the next 15 years are unrecorded, though he was likely still living in his father’s home most of that time. However, at some point he joined the tide of migrants flowing into Tidewater Virginia, and, on 13 January 1897, in Norfolk, Virginia, Hayward Artis, age 26, born in North Carolina to A. and F. Artis, married Hattie E. Hawthorn, 23, born in Virginia to J. and E. Hawthorn. As early as 1897, Haywood began appearing in city directories for Norfolk, Virginia. Here, for example, is Hill’s City Directory for 1898:

Haywood and Hattie and their children Bertha E., 3, and Jessie, 11 months, appeared in the 1900 census of Tanners Creek township, Norfolk County, Virginia. The family resided on Johnston Street, and Haywood worked as a porter at a jewelry store. Ten years later, they were in the same area. Haywood was working as a farm laborer, and Hattie reported four or her seven children living — Bertha, 12, Jessie, 11, Hattie, 8, and M. Willie, 2.

In the 1920 census of Monroe Ward, Norfolk, Haywood and Harriet Artis appear with children Elnora, 22, Jessie, 20, Hattie, 18, Willie Mae, 12, Haywood Jr., 8, and Charlie, 5. Haywood was a farm operator on a truck farm, daughters Elnora and Hattie were stemmers at a tobacco factory, and son Jesse was a laborer for house builders.

By 1930, the Artises were renting a house at Calvert Street. Heywood Artis headed an extended household that included wife Harriett, Haywood jr. (laborer at odd jobs), Charles, son-in-law Daniel Johnson (machinist for U.S. government) and his wife Hattie (bag maker at factory), cousins Henry Sample, Raymond G. Mickle, and Lois Sample, and granddaughters Mabel Johnson, 2, Olivia Washington, 15, and Lucille, 13, Bertha, 9, and Lois Brown, 6.

On 19 March 1955, Haywood Artis’ obituary appeared in the Norfolk Journal and Guide:

Haywood Artis, who has made his home in Norfolk for some 65 years, was buried following impressive funeral rites held at Hale’s funeral home March 7 with the Rev. W. H. Evans officiating.

Mr. Artis died March 4 at the home of his daughter, Mrs. Willie Mae Yancey, 2734 Beechmont avenue, after a long illness.

Mr. Artis, who was born in Goldsboro, NC, is survived by three daughters, Mesdames Elnora Brown, Hattie Johnson and Willie Mae Yancey, all of Norfolk, and a son, Hayward Jr., of New Jersey.

There are also 34 grandchildren, 33 great-grandchildren and other relatives and friends.

Interment was in Calvary Cemetery.

Thanks to B.G. for the copy of his great-great-grandfather Haywood Artis’ photograph.