Another example of the pitfalls of unquestioning acceptance of federal population schedules at face value. What you see (1) may not be what it seems and (2) is not all there is. Here, I follow my great-great-great-grandfather Adam T. Artis over the arc of his life, as recorded in census records.

Adam Artis was born in 1831 to a free woman, Vicey Artis, and her enslaved husband, Solomon Williams, most likely in Wayne or Greene Counties, North Carolina. In the 1840 census of one of those counties, he, his mother and siblings are anonymous hashmarks under the heading “free colored people” alongside the name of a white head of household.

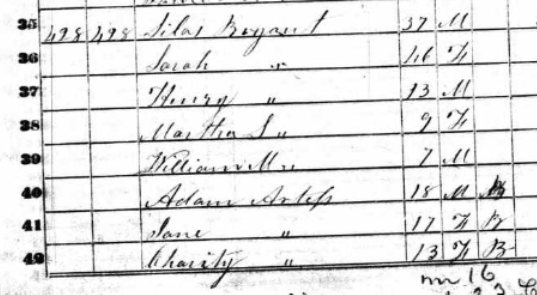

The 1850 census of Greene County is the first record of Adam’s existence:

White farmer Silas Bryant is the head of household. The other Bryants are presumably his wife and children. The significance of Adam Artess, Jane Artess and Charity Artess’ names listed below requires knowledge outside the four corners of the page. As I learned via subsequent research, Jane and Charity were Adam’s sisters. (Their mother and remaining siblings were listed next door at #429.) Though no bonds or other indenture documents survive, it is most likely that the Artis children were involuntarily apprenticed to Bryant until age 21 by the Greene County Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions. Adam’s age is correct, so I assume that Jane’s and Charity’s are, too. The censustaker evinced some hesitation in describing Adam’s color, appearing to superimpose a B (black) over an M (mulatto.) This is a matter of some concern to descendants who deny that he was of African descent. No photographs of Adam survive, but his great-granddaughter D.B. told me she recalls seeing one in her childhood. It was later stored in a barn and ruined by rainwater. Adam, she said, was brown-skinned. Mulattohood was in the eye of the beholder, but I think it is safe to say that Adam had considerable African ancestry.

The 1860 census of the North Side of the Neuse River, Wayne County, tells a nuanced story. This entry contains the sole census reference to Adam’s skills as a carpenter, probably gained during his apprenticeship to Bryant. The $200 in personal property probably consisted mostly of the tools of his trade, and the $100 value of real property reflects his early land purchases. (I found a deed in Wayne County for Adam’s sale of ten acres to his brother-in-law John Wilson in 1855. The sale was a buyback, but Adam never recorded a deed for the original purchase.) Adam was a widower in 1860, and Kerney, Noah and Mary Jane were his children by deceased wife Lucinda Jones Artis. They were not his only children, however. His oldest two, Cain and Caroline, were enslaved alongside their mother Winnie Coley, and are not named in any census prior to 1870.) Jane Artis was Adam’s sister. Her age is about right, though his is off by a year or so. Her one month-old infant may have been daughter Cornelia, who is listed in the 1870 census as born in 1860. I’ve included two lines of the next household to highlight a common pitfall — making assumptions about relationships based on shared surnames. Though they were Artises and lived next door, Celia and Simon were not related to Adam Artis. At least, not in any immediate way. (Ultimately, nearly all Artises trace their lineage to a common ancestor in 17th-century Tidewater Virginia.) Adam’s son Jesse Artis testified directly to the matter in the trial in Coley v. Artis: “I don’t know that Tom and I are any kin. Just by marriage.”

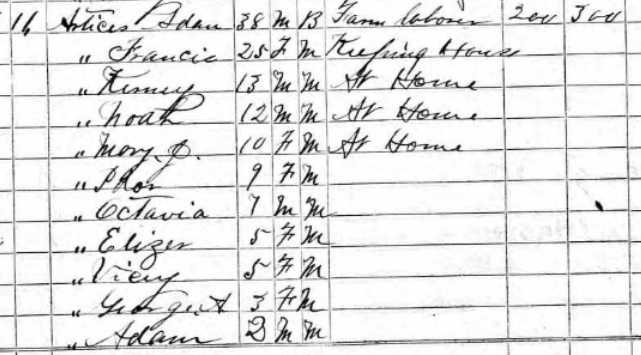

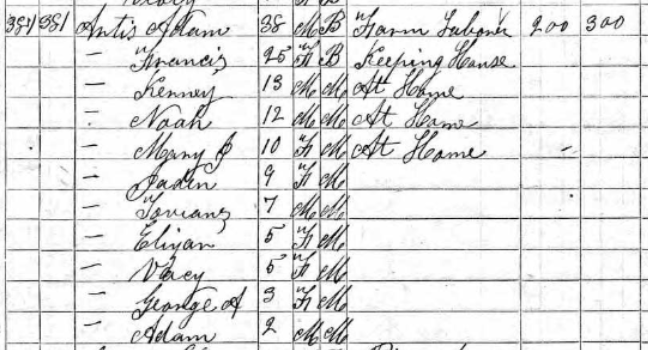

So far, we’ve found basically accurate, if deceptively simple, census entries. 1870 is where the trouble starts. There’s this:

But wait. There’s this, too:

The first entry is found in the enumeration of Holden township, Wayne County. The second is in Nahunta. The first was taken 18 August by William R. Perkins. The second, 23 September. By William R. Perkins.

Huh?

I can’t begin to explain why Perkins rode the backlanes of northeast Wayne County twice and — in two different handwritings — recorded the same people living in the same houses as residents of different townships. Substantively, though, with a couple of exceptions, the two households attributed to Adam Artis are quite consistent. Adam and his wife Frances (Seaberry, whom he married in 1861) are shown with nine children whose ages are identical in both listings. The last six children were born to Frances, and some of their names take a gentle mauling between records. The oldest child was Ida, which is close to “Idar,” but not at all to the very modern-sounding “Jaden.” And who was Octavia/Tavious, a seven year-old male? Process of comparison and elimination identifies him as Napoleon Artis, often called Dock. Was Octavius his middle name? I’ve ever seen it used in any other place.

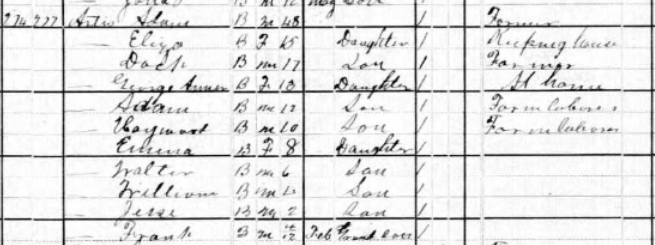

Fast forward ten years to 1880:

Adam is again a widower, as wife Frances died shortly after the birth of son Jesse. Daughter Eliza is helping care for her eight siblings, plus grandbaby Frank, whose mother or father I have never been able to identify. (I have not even found clear evidence of Frank in any later record.) This living situation was not tenable, and Adam married again that very year to Amanda Aldridge, his son-in-law’s sister. Tragically, Adam and Amanda’s marriage was never recorded in a census record as she died days after the birth of her last child, Amanda Alberta, in 1899. Thus, Adam is a widower once more in 1900:

“Artice” is an alternate spelling of Artis seldom used by Artises themselves, but occasionally adopted by those recording them. In this record, two of Adam’s children with Frances, Walter and William, were still unmarried and living at home, but the remaining children are Amanda’s. Don’t be fooled by the absence of the infant Alberta. She survived her mother’s untimely death and was taken in by her half-sister Louvicey Artis Aldridge, who, presumably, nursed her along her own babies.

Adam remarried in 1903. The 1910 census accurately reflects his four legal marriages. (His informal relationship with Winnie Coley is omitted.) His latest (and last) bride, Katie Pettiford, was 50+ years his junior. All of his older children have left (or fled) the nest except 12 year-old Annie Deliah Artis, whose status as “husband’s daughter” is carefully noted. Alphonzo Pinkney Artis was Adam’s last surviving child, though Katie reported giving birth to two others. Alberta was still with John and Vicey Aldridge — listed as “Elberta,” a “granddaughter,” speaking of misinformation — in their household at the other end of Wayne County in Brogden township. (Family stories say that this arrangement ended unhappily when Alberta learned, in her early teens, that she was not, in fact, Vicey and John Aldridge‘s child.)

There is no 1920 census entry for Adam T. Artis. This father of nearly 30 children (23 of whom are listed with him in census records) and husband or partner of five (only two of whom show up in the census) died the 11th day of February, 1919.