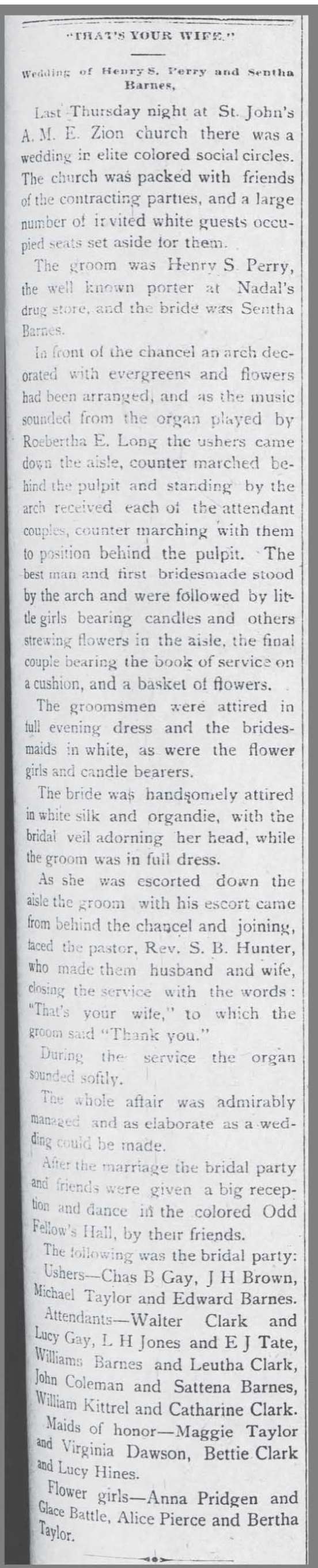

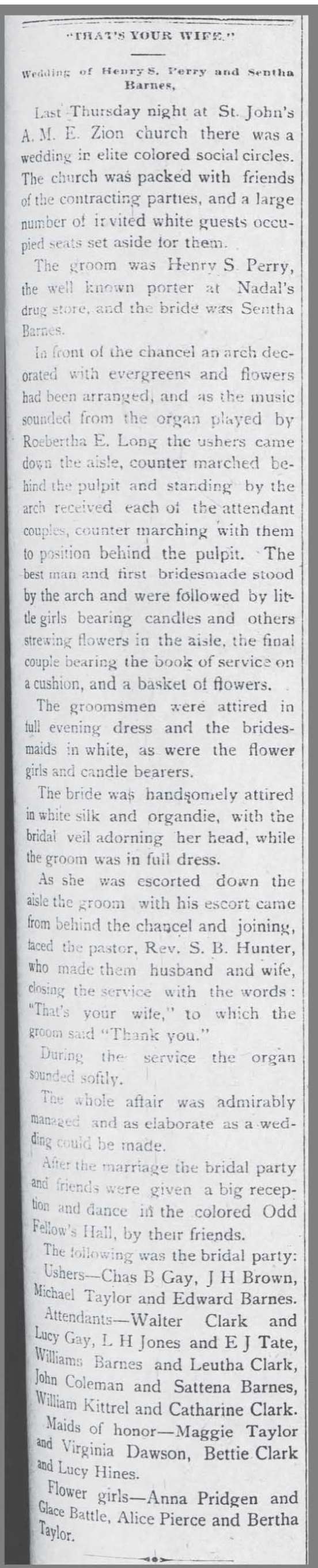

Wilson News, 21 September 1899.

(Ignore the snark, which was par for the course for newspapers covering African-American social and cultural events.)

I came across this article using my great-grandfather’s name as a search term. Mike Taylor was an usher at this wedding and, look, so was his brother-in-law Edward Barnes. Mike’s daughter Maggie Taylor, my grandfather’s sister, then about 13, was a maid of honor, and his daughter Bertha Taylor, 7, was a flower girl. The bride and groom were Henry Perry and Centha Barnes. Were either of them related to the Taylors?

“Perry” rang a little bell. In the 1910 census of Wilson, Wilson County, living along the A.C.L. Railroad: 42 year-old railroad laborer Pierce Barnes, wife Mary, 34, adopted son Robert Perry, 8, and Mary’s father Willis Barnes, 72. Mary was my great-grandmother Rachel Barnes Taylor‘s sister. In the 1920 census of Wilson, Wilson County, at 114 Lee Street: Mike H. Taylor, cook at cafe, wife Rachel and their son Tom Perry, 12.

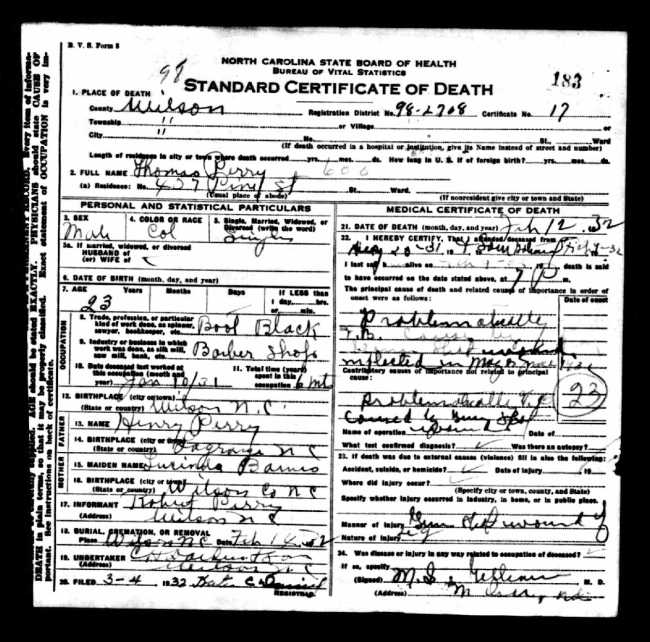

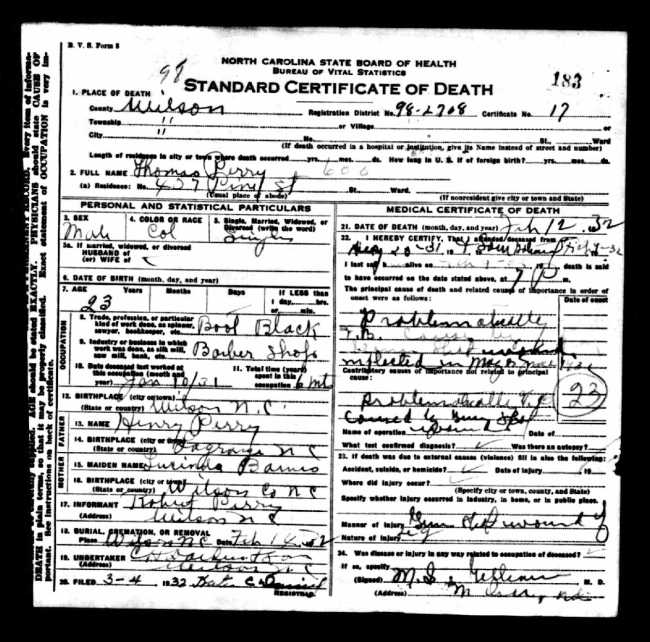

Then there was this death certificate:

So Tom Perry was the son of the couple that married above. But what was Tom’s relationship to Robert Perry, who was adopted by Mary Barnes Barnes and served as informant for Tom’s death certificate? And how were the Perrys related to Mike Taylor or his wife Rachel Barnes Taylor?

I found Henry and Centha Barnes Perry’s 1899 marriage license. Henry was 24; Centha, 18. Both Henry’s parents were listed, but only her father, Willis Barnes, was.

In the 1880 census of Wilson township, Wilson County, Willis Barnes appears with his wife Cherry, six of their children (the youngest aged about 4) and a niece. By 1900, and probably long before, Cherry Battle Barnes was dead. Had she had one last child, Lucinda, called “Centha,” in 1881?

Let’s say Cherry died in or shortly after childbirth. Her oldest daughter Rachel, who married Mike Taylor in 1882, likely would have reared her baby sister with her own children. (The oldest, my grandfather, was born in 1883.) The 1890 census might have captured this family together, but those records were destroyed by fire. By 1900, Centha (“Sindie”) and her new husband Henry S. Perry were living together in Wilson, as yet childless. Ten years later, however, Henry was listed as a single man boarding at the New Briggs Hotel, where he worked as a bellboy.

What happened in those ten years? The best guess is that Cintha, having given birth to at least two sons, Robert (1903) and Thomas (1908), died. Her children went to live with her mother’s relatives, just as she had done. The family, however, never quite recovered. Henry eventually remarried, but died in 1927 when his second set of children were still young. Tom, who worked as a boot black in a barbershop (perhaps the one in which my grandfather cut hair), was shot in the leg in the spring of 1931, then seems to have died of tuberculosis less than a year later. (Cause of death: “problematically T.B. caused by gun shot wound”? Wha?) Robert Perry worked as a grocery delivery boy for a while, then as a janitor for Carolina Telephone & Telegraph Company, but in 1930 was listed as a convict living at the Wilson County Stockade. He married a woman named Pauline, but it is not clear whether they had children. In 1942, he registered for the World War II draft:

The back of the card notes that Robert Lee Perry was 5’11”, 155 lbs., had a scar under his left eye, and had brown eyes, black hair and a dark brown complexion. “Mike Taylor,” the person who would always know his address, was not the Mike Taylor who had been an usher at his parents’ wedding. Rather, he was that Mike’s son, Roderick “Mike” Taylor, Robert’s first cousin and my grandfather. Robert Perry died 15 May 1977. His death certificate lists no parents.