Me: And you said he looked just like your dad. Your dad looked just like his father.

My grandmother: Papa looked just like him. And one thing, with all that white in him, he was brown like Grandpa.

Me: Unh-uh.

Grandma: And I don’t know who Mat and Golar and Walker’s mother was, but Walker was real dark. But handsome. Honey, he was one beautiful child and had this pretty hair. Curly. And it wouldn’t even keep a part or nothing in it. And he came home one time, and he had cut this part, cut this place through his hair. And he said his friends had parts in their hair, but his was so curly it wouldn’t stay. So he had to cut this part. Another time, that was just after Mama had married Papa. And she was just so crazy ‘bout him, he was such a pretty little boy. And she made him this velvet suit.

My aunt L.: Who, Walker?

Grandma: Walker. Fauntleroy. You know what a Fauntleroy suit is?

Me: Mm-hmm.

Grandma: She made him this Fauntleroy suit for commencement. And she said it had this little collar, you know [inaudible] collar. And said when Walker came out on the stage to do his part, he had stuffed all that collar on the inside of his coat and pulled them sleeves down. [Laughing.] Mama said, “See. Will you look at this young’un.” [Laughing.]

Me: ‘Cause they were fairly young, right, when —

Grandma: Yeah, they were six — something like six, eight and ten. And they may have been younger than that.

Me: And their mother died?

Grandma: Yeah. I don’t know how she died. But her sisters were really nice to Mama. Oh, they were really nice to her. Mama loved them like her own sisters. They were so nice to her. And, see, they were sort of taking care of the children while Papa was in between two marriages you know.

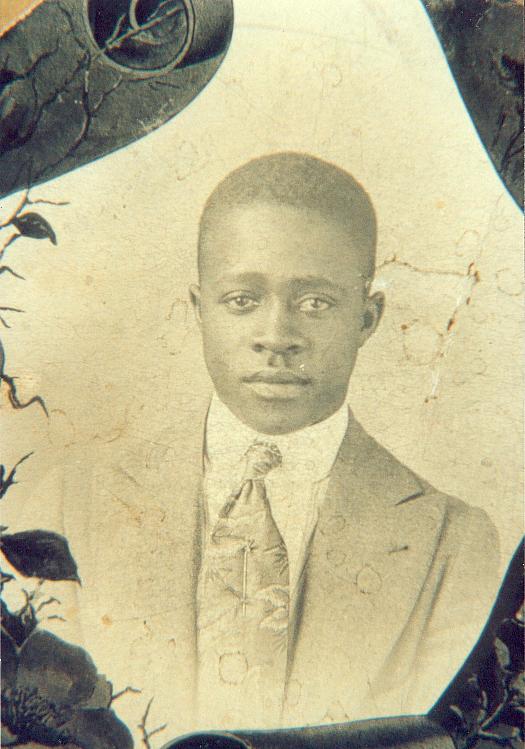

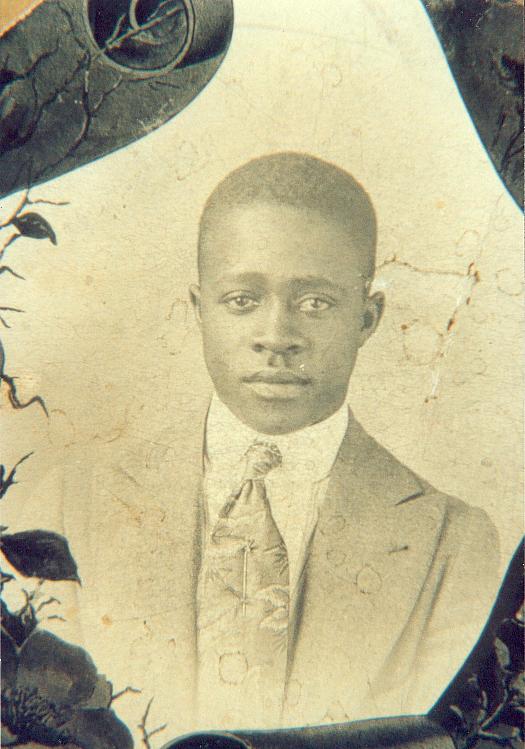

J. Walker Colvert II, perhaps in his early twenties.

——

So, who was Lon Colvert’s first wife? I know her name — Josephine Dalton — but little else.

In the 1880 census of Eagle Mills, Iredell County, one year-old Josapene Dalton is listed in the household of her parents, Anderson and Vincey Dalton, along with brother Andrew, 17; sister Mary B., 3; her great-grandmother, Mary Houston, 85; and a boarder named Joe Blackburn, 28. The family lived among a little cluster of Dalton households, the first headed by 67 year-old John H. Dalton, a white farmer. Dalton, born in Rockingham County, North Carolina, arrived in Iredell County in 1840’s. He married the daughter of Placebo Houston, a prominent planter, and is credited with introducing tobacco cultivation in Iredell County. According to a 8 April 1974 article in the Statesville Record and Landmark, by 1850 Dalton had established a tobacco plug factory that employed 17, but had to haul bright leaf tobacco from counties along the Virginia line. This scarcity drove his efforts to jumpstart local tobacco production. In 1858, John Hunter Dalton built Daltonia, described as “an imposing Greek Revival house whose richness and diversity of detail make it one of the most architecturally outstanding houses” in the county. The 1860 census counted among Dalton’s possessions 57 slaves living in eight houses. Josephine Dalton’s father, and maybe her mother, were likely among them.

Josephine was born well after the Civil War — after Reconstruction even — but her family seems to have remained tethered to Daltonia for decades after Emancipation. [After I started this blog post, I traveled to Iredell County, met P.P., and visited Daltonia. That story, and more about Josephine’s family, is here.] Sometime around 1894 — I have not located a license — Josephine married Lon W. Colvert, an ambitious 19 year-old Eagle Mills native set to make his mark in the town of Statesville. [Update, 4/6/2015: license found.] The young family appears in the 1900 census of Statesville, Iredell County — Lon Colvert, 25, wife “Joseph,” 23, and children Gola, 5, Mattie, 4, and Walker, 2. No more than five years later, Josephine was dead.