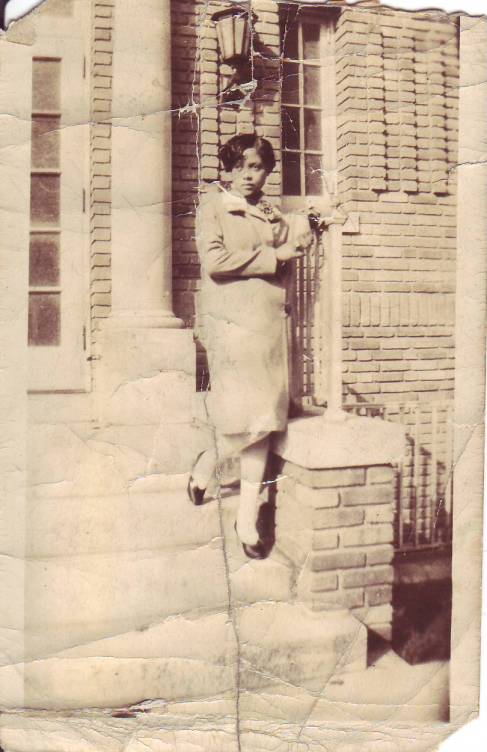

Bessie died when I was eight months old. And Mama Sarah took me as a baby and brought me to Wilson. And her husband was the only papa I knew. His daughters all disliked me being there, but I loved him and he loved me. But they all just said he loved me better than he did them, and I wont nothing no kin to him. But when you take a child that’s with you all the time, and every Sunday you send to the store to get you some oil to wash your feet … just nobody but me there. Nobody but Mama, Papa, and me. Mamie wasn’t even there then. She was down in Dudley with Grandma Mag. And so, I guess he just learned to love me. And he told me, if I wanted to stay with him, I could stay, and if he didn’t have but one biscuit, he’d divide it and give me one half and he’d have the other half. And that way I wanted to go with him ‘cause Mama’d fuss all the time. She was always talking, got to be doing something. And so I wanted to follow him. And so I went with him everywhere.

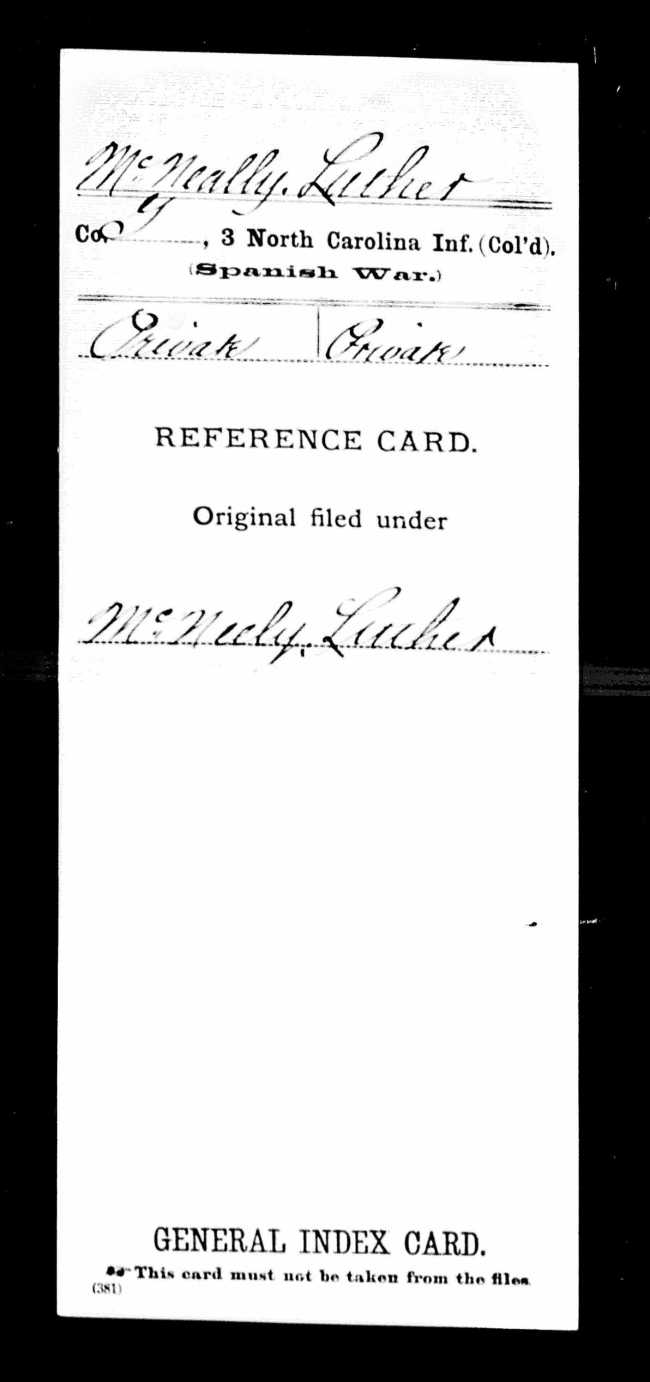

In late 1895, the freshly widowed Jesse Adams Jacobs Jr. married Sarah Daisy Henderson in Dudley, Wayne County. He brought children as young as a year old to the marriage, and she brought a daughter, a niece and a nephew. Around 1905, Jesse, Sarah, his youngest children and her nephew Jesse Henderson joined the flow of farm dwellers to Wilson, then entering into its golden era as the World’s Largest Tobacco Market. A couple of years later, when Sarah’s niece, Bessie Henderson, died, Jesse and Sarah took in her small children, the younger of which was my grandmother.

Jesse was born in 1856 in Sampson County to Jesse Jacobs Sr., a prosperous free colored farmer, and his wife Abigail. Many of Jesse and Abigail’s modern descendants are members of the Coharie Native American tribe. Others, like Jesse Jr.’s descendants, identify as African-American.

Jesse A. Jacobs bought a small house at 303 Elba Street in 1908. Over the years, he worked as a hostler and a janitor and for extra cash farmed small plots of land he rented on the edge of town. My grandmother was his constant companion.

And so I wanted to follow him. And so I went with him. Up there to First Baptist Church, help him dust the seats, and he’d run the sweeper and all that kind of stuff. And when he was over to another school up there, the college. He used to be janitor to the college. And then he had the school out there at Five Points. Winstead School out there at Five Points. And I would be the one at all those places. Go cut Professor Coon’s grass, I’d be right with him. And then, out to Five Points. I went out there – I was in school ‘cause I run all the way from up the school, came by the house, get me a bite to eat and run from there to clean to Five Points School where was out there – white folks. And sweep up that whole building by myself. Papa’s down there in the field, up there by – uh, what is the people be putting them … they had chains on their legs and had the white stripes – convicts. It was a place up there. And I’d go ‘round there and sweep that whole building up by myself. Papa was gon get me a bicycle so I could ride over there. ‘Cause, see, he had the horse and wagon, and so he was already over there, and he had been there by where the pigpen was down by that little stream, that little ditch. And I’d come back on the wagon at night with him. But while he was plowing, ‘cross the street over there where he had a acre of cotton. And while he was working, plowing that garden where was on the side, Professor Coon let him have whatever he put in it. He would buy all the stuff to go in the ground, if Papa would just work it. So he’d plant that, and then me and Mamie had to get up two o’clock in the morning, go down there and pick up potatoes. Light night. It’d be so bright you could see ‘em. He’d plow it up, turn that ground over, and all them old potatoes down there, put ’em in baskets, and what we couldn’t see ‘fore it got real daylight, we had to go out there and pick ‘em up when it got day.

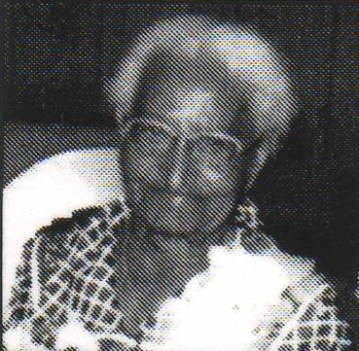

My grandmother’s young life was difficult, and she carried scars of hurt and disappointment even into the years that I knew her. But her voice always softened when she spoke of her adored Papa, the single source of unconditional love in her childhood.

I used to brush Papa’s hair. He didn’t have much. Take one of them soft brushes, hand brushes. Two of ‘em, he brought ‘em from New York. He brought the brushes home, and I was always messing with his hair. And I’d get the brush and hold it on one side and part it off and brush it down. It was real soft. And near ‘bout all of it come off where was on top. And I was always asking a nickel, a penny: “What, ain’t you got some change in your pocket? I want to go the store.” So I was feeling his legs, feeling for pennies or nickels up there. So I said, want to know if he’d give me a nickel, or give me a penny, or whatever it is. So he run his hand in his pocket, a penny or a nickel or whatever, he’d give it to me. I’d go on to the store, and he said, “Wait. Wait a minute.” He had to have tobacco. So then he’d give me a dollar. And he told me to go down to the store down, right down there from our house. Old Man Bell’s store, the white man that run the store. “Get me a quarter. Don’t spend it all.” It’s three sections or four sections on a plug of tobacco. And they cut into it where the cracks is, and it sells for so much. And so I’d go down there to the store and get it and come back and give it to him.

——

Original photo of Jesse and Sarah H. Jacobs on their wedding day in the collection of Lisa Y. Henderson. Edited excerpts from interviews of Hattie H. Ricks by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved.