Newport News, Virginia, late 1950s.

Category Archives: Photographs

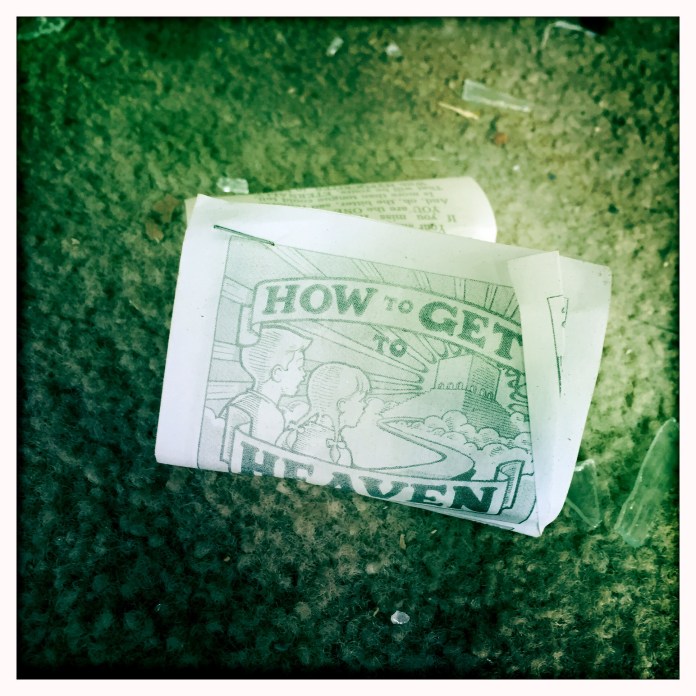

Slow death.

One of these days, I’m going to go home, and it’s not going to be there. I’m going to drive to Elba Street, and there will be nothing at 303 but weeds, broken brick and shards of glass. This time was not the time, but it ain’t long coming.

A Kerchief of Sense.

Timed to coincide with the anniversaries of his father’s birth in 1923 and his mother’s death in 1963, Effenus Henderson‘s recent memoir, A Kerchief of Sense, is available at Amazon.com. It is a simultaneously heart-breaking and heart-warming story of family and faith.

So much of what Effenus has written of occurred during the period that our branches of both the Henderson and Aldridge families had lost contact. I found my way back to them through my grandmother and father, who often mentioned that we had a cousin called Snook — Horace Henderson — still down in Dudley. My grandmother only knew bits and pieces of the story told here, but her recollections led to our reconnection with his children and our larger family. Tribulation was no stranger to either of our lines, but we survived and now thrive. Thank you, Effenus, for capturing this aspect of our common legacy.

Horace Henderson Sr. and his twelve children, 1963.

L2 Legacy. (And well wishes!)

My niece turned 18 today. She’s the only one of my grandmother Margaret Colvert Allen‘s great-grandchildren to carry her mtDNA haplotype — L2d1a. I’m feeling some kind of way about that, and I shared my wistfulness with a group of researchers with whom I’m fortunate to co-administer a Facebook genealogy group. J. immediately replied that I should consider taking an mtDNA Full Sequence test at FTDNA. Though in the immediate sense the test is of limited genealogical use, as she wisely pointed out, the mtDNA database will never grow if none of us contributes to it.

Arising approximately 90,000 years ago, L2 is one of the oldest of the matrilineal haplogroups and is the most common African lineage. L2d1a, however, is a relatively rare subclade. Google it, and three of the top five references are to this blog. I have no children and will not pass along Martha M. McNeely‘s matrilineage in that way. However, I can contribute to the understanding of its history and keep Martha’s legacy alive otherwise. Stay tuned, and Happy Birthday, S.D.J.!

Martha Margaret Miller McNeely’s L2d1a progeny — my grandmother, my sister, my niece, my mother, 1998.

Adam’s diaspora: Haywood Artis.

I’ve written here and here about the migration of Adam T. Artis‘ children Gus K. and Eliza to Arkansas. Though most of his 30 or so children remained in North Carolina, a few went in North. Or, at least, a little further north. One was Haywood Artis, born about 1870 to Adam and his wife Frances Seaberry Artis. He was my great-great-grandmother Vicey‘s full brother.

Haywood Artis

In the 1880 census of Nahunta, township, Wayne County, North Carolina, Adam Artis, widowed mulatto farmer, is listed with children Eliza, Dock, George Anner, Adam, Hayward, Emma, Walter, William, and Jesse, and four month-old grandson Frank Artis. (I’ve never been able to determine whose child Frank is.]

Haywood’s whereabouts over the next 15 years are unrecorded, though he was likely still living in his father’s home most of that time. However, at some point he joined the tide of migrants flowing into Tidewater Virginia, and, on 13 January 1897, in Norfolk, Virginia, Hayward Artis, age 26, born in North Carolina to A. and F. Artis, married Hattie E. Hawthorn, 23, born in Virginia to J. and E. Hawthorn. As early as 1897, Haywood began appearing in city directories for Norfolk, Virginia. Here, for example, is Hill’s City Directory for 1898:

Haywood and Hattie and their children Bertha E., 3, and Jessie, 11 months, appeared in the 1900 census of Tanners Creek township, Norfolk County, Virginia. The family resided on Johnston Street, and Haywood worked as a porter at a jewelry store. Ten years later, they were in the same area. Haywood was working as a farm laborer, and Hattie reported four or her seven children living — Bertha, 12, Jessie, 11, Hattie, 8, and M. Willie, 2.

In the 1920 census of Monroe Ward, Norfolk, Haywood and Harriet Artis appear with children Elnora, 22, Jessie, 20, Hattie, 18, Willie Mae, 12, Haywood Jr., 8, and Charlie, 5. Haywood was a farm operator on a truck farm, daughters Elnora and Hattie were stemmers at a tobacco factory, and son Jesse was a laborer for house builders.

By 1930, the Artises were renting a house at Calvert Street. Heywood Artis headed an extended household that included wife Harriett, Haywood jr. (laborer at odd jobs), Charles, son-in-law Daniel Johnson (machinist for U.S. government) and his wife Hattie (bag maker at factory), cousins Henry Sample, Raymond G. Mickle, and Lois Sample, and granddaughters Mabel Johnson, 2, Olivia Washington, 15, and Lucille, 13, Bertha, 9, and Lois Brown, 6.

On 19 March 1955, Haywood Artis’ obituary appeared in the Norfolk Journal and Guide:

Haywood Artis, who has made his home in Norfolk for some 65 years, was buried following impressive funeral rites held at Hale’s funeral home March 7 with the Rev. W. H. Evans officiating.

Mr. Artis died March 4 at the home of his daughter, Mrs. Willie Mae Yancey, 2734 Beechmont avenue, after a long illness.

Mr. Artis, who was born in Goldsboro, NC, is survived by three daughters, Mesdames Elnora Brown, Hattie Johnson and Willie Mae Yancey, all of Norfolk, and a son, Hayward Jr., of New Jersey.

There are also 34 grandchildren, 33 great-grandchildren and other relatives and friends.

Interment was in Calvary Cemetery.

Thanks to B.G. for the copy of his great-great-grandfather Haywood Artis’ photograph.

A terrible thought ….

I ran across this article in the 19 May 1933 edition of the Statesville Landmark detailing the tragic death of a boy playing in the Green Street (then Union Grove) cemetery.

“… Five pieces of marble — two in the base, two parallel upright pieces, seven inches apart, and a horizontal top piece.”

I been all through this cemetery. There are relatively few markers there. This, however, still stands. It is the double headstone of my great-great-grandfather John W. Colvert and his wife Adeline Hampton Colvert. Though it is possible that there once were others, it is now the only one of its kind in Green Street. Was this the monument that killed Noisey Stevenson?

Roadtrip chronicles, no. 6: Western Rowan County churches.

In Church Home, no. 9, I wrote about Back Creek Presbyterian, the church that my great-great-great-great-grandfather Samuel McNeely helped found and lead. I wanted to see this lovely edifice, erected in 1857, for myself:

And I wanted to walk its cemetery. I didn’t expect to see the graves of any of its many enslaved church members there, but thought I might find Samuel McNeely or his son John W. Dozens of McNeelys lie here, many John’s close kin and contemporaries, but I did not find markers for him or his father. (I later checked a Back Creek cemetery census at the Iredell County library. They are not listed.)

Within a few miles of Back Creek stands its mother church, Thyatira Presbyterian. This lovely building was built 1858-1860, but the church dates to as early as 1747. There are McNeelys in Thyatira’s cemetery, too, and this is the church Samuel originally attended.

Just up White Road from Thyatira is Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church. I visited its cemetery in December 2013 and took photos of the the graves of descendants of Joseph Archy McNeely (my great-great-grandfather Henry McNeely‘s nephew), Mary Caroline McConnaughey Miller and John B. McConnaughey (siblings of Henry’s wife, my great-great-grandmother Martha Miller McNeely.) Green Miller and Ransom Miller’s lands were in the vicinity of this church.

Photos taken by Lisa Y. Henderson, February 2015.

Roadtrip chronicles, no. 5: Daltonia.

I saw that big, block of a white house, but I didn’t know what I was looking at. And, really, I wasn’t even much looking at it, because my whole attention was zeroed on a small building a couple hundred feet beside and behind it. A one and-a-half story log cabin sitting on fieldstone piers, mud-chinked, with small windows in the gable ends and central front door. In pristine condition. What was this?

I turned to P.P., who shifted uncomfortably in her seat. “I don’t even want to say this,” she started, “but it’s true. It’s just so ugly.”

“Please do. Please do,” I urged.

“Well, the official story is that’s where the Daltons lived while they were building the house.”

The house — oh. This was Daltonia.

“But that log cabin was Anse Dalton’s house.”

Wait. “Anse Dalton!? Anderson Dalton? That was — he was the father of my great-grandfather Lon W. Colvert‘s first wife, Josephine.”

“Yes, well, after the War, he was a driver for the Daltons. But in slavery …”

Yes? “In slavery, he was a — I hate to say it — he was used to breed slaves. That’s what they called this — ‘the slave farm.'”

I sat with that for a minute.

“It’s terrible,” she continued. “They thought, just like you can disposition an animal, you could breed people with certain traits. He had I-don’t-know-how-many children.”

I knew about slave breeding, of course. About the sexual coercion of both enslaved men and women, particularly in the Upper South. I’ve read slave narratives that speak of “stockmen,” but never expected to encounter one in my research. I thanked P.P. for her openness, for her willingness to share the stories that so often remain locked away from African-American descendants of enslaved people. Not long ago, I started working on a “collateral kin” post about the Daltons. I knew Josephine Dalton was born about 1878 to Anderson and Viney (or Vincey) Dalton; that her siblings included Andrew (1863), Mary Bell (1876), Millard (1880), Lizzie (1885) and Emma (1890); and that she was from the Harmony/Houstonville area. I’d stumbled upon articles about Daltonia and had conjectured that her parents had belonged to wealthy farmer John Hunter Dalton. I’d set the piece aside for a while though, because I had no specific evidence of the link beyond a shared surname. However, here was an oral history that not only placed Josephine’s father among Dalton’s slaves, but detailed the specific role he was forced to play in Daltonia’s economic and social structure.

P.P. did not know Anse Dalton, but Anse’s son Millard and her grandfather had grown up together. P.P. was reared in her grandfather’s household and vividly recalled Millard Dalton riding up to visit on his old white horse. “You can have her till I go home,” he’d tell her as he handed off the reins.

I can finish my Dalton piece now. Though I will never know the names of the children that Anderson fathered as a “stockman,” genealogical DNA testing may yet tell the tale, and I have a clearer picture of Josephine Dalton Colvert’s family and early life.

Photographs taken by Lisa Y. Henderson, February 2015.

52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks: 7. Love.

My parents celebrate 54 years of marriage in May, God willing. They have always been my model of deep and enduring love, and I have celebrated them here. For this week’s Ancestor Challenge, I’ve chosen to highlight a different kind of love.

My grandmother, Hattie Mae Henderson Ricks, and her sister, Mamie Lee Henderson Holt, were born into difficult circumstances. Their mother Bessie Lee Henderson, teenaged and unmarried, had been orphaned as a toddler. When Bessie died months after Hattie’s birth, the family gathered to decide who would rear the girls. Mamie remained in Dudley with their aged great-grandparents, Lewis and Margaret Henderson, and Hattie went to Wilson to live with their grandmother’s sister, Sarah Henderson Jacobs. They were not reunited until Grandma Mag’s death, when Mamie was 8 and Hattie, 5. They separated again just 7 years later, when Mamie married a young man she met while visiting relatives in Greensboro. Nonetheless, despite the short time they lived together in childhood, my grandmother and her sister were devoted to one another. Their fierce sisterly bond defied the uncertainty of their earliest years and the emotional neglect of their years with Mama Sarah. It knit their children and grandchildren in a web that continues to hold. Even my grandmother’s move to Philadelphia in 1958 did not shake it. Every Christmas, she visited us and my aunt’s family in Wilson, then my father drove her to Greensboro to bring in the New Year with the Holts. Eventually, Alzheimer’s began to claim Aunt Mamie’s mind and memories, and travel became too difficult for my grandmother, but her attachment did not waver. Only when Aunt Mamie passed did my grandmother begin to let go. Nine months later, almost to the day, she was gone.

After my grandmother passed in 2001, I found a note she wrote about her early life: Heart Broken Mother – Bessie Died age Nineteen Leaving two out of wedlock Girls arounds 3 years and 8 months old. … My sister and I always felt very close to each other as we had no real parents It had been a hard life for both of us

This is the love I celebrate in this week’s challenge. The first love that comes with family. The love that, if we are fortunate, endures the entire arc of life.

Mamie and Hattie Mae Henderson, circa 1920.

The sisters, probably in Greensboro, 1940s.

The sisters on Aunt Mamie’s porch in Greensboro, probably late 1980s.

Roadtrip Chronicles, no. 1: Statesville cemeteries.

I made it to Statesville in good time Sunday and drove straight to the only place I really know there — South Green Street. My great-aunt, Louise Colvert Renwick, had lived there for decades, across from the street from the Green Street cemetery. As I approached her house, my eye caught a small memorial just off the curb.

Funny what you see when you’re looking. (And look closely at the plaque. Committee member Natalie Renwick is my first cousin, once removed.)

It seems odd to me that, when we were all gathered at Aunt Louise’s for the first Colvert-McNeely reunion, no one mentioned that Colverts and McNeelys were buried across the street. (Or maybe my 14 year-old self just paid no attention?) I’ve only found three graves — those of John Colvert, his wife Addie Hampton Colvert, and their daughter Selma — but there are certainly many more. Lon W. Colvert, for one. (Or was it? His death certificate indicates “Union Grove,” but why would he have been buried up there?*) And his son John W. Colvert II. And Addie McNeely Smith and Elethea McNeely Weaver and Irving McNeely Weaver, who was brought home from New Jersey for burial.

The cemetery looks like this though:

And not because it’s empty. Though closed to burials for 50 or more years, it is probably nearly full of graves either unmarked or with lost or destroyed markers. Here’s one that’s nicely marked, however, and that would I recall before 24 hours had passed:

From Green Street, I headed across town to Belmont, Statesville’s newer black cemetery. I knew Aunt Louise, her husband and son Lewis C. Renwick Sr. and Jr. were buried in Belmont, and I was looking for several McNeelys whose death certificates noted their burials here. I found Ida Mae Colvert Stockton‘s daughter Lillie Stockton Ramseur (1911-1980) and her husband Samuel S. Ramseur (1912-1989). Then Golar Colvert Bradshaw‘s husband William Bradshaw (1894-1955) and son William Colvert Bradshaw (1921-1988). (William was buried with his second wife. Golar, who died in 1937, presumably was interred at Green Street.) No McNeelys though. I expected to find both Lizzie McNeely Long and Edward McNeely, who had a double funeral in 1950, but their graves seem to be unmarked.

I was also looking for my great-grandmother, Carrie McNeely Colvert Taylor. The whole business was turning into a big disappointment. At street’s edge, I turned to head back to my car. And gasped. There, at my feet, wedged at the base of a tree:

What in the world? This is clearly not a gravesite. And, on the other side of the tree, there’s an identical stamped concrete marker for Lewis C. Renwick Sr., who died almost exactly a year after Carrie. What’s odd, though, is that he has a granite marker a couple hundred feet away in another section of the cemetery with his wife (Carrie’s daughter Louise) and oldest son. Is Grandma Carrie actually buried in the Renwicks’ family plot? Were her and Lewis Renwick’s makeshift stones pulled up to be replaced by better markers? If so, where is Grandma Carrie’s? And why were both dumped at the edge of the cemetery?

Here’s an overview of Belmont cemetery. (1) is the approximate location of Carrie M.C. Taylor’s broken marker. (2) is the approximate location of the Renwick plot.

I’ll pose those questions to Statesville’s cemetery department. If Grandma Carrie has no permanent stone, she’ll get one.

* After noticing that Irving Weaver’s obit also mentioned Union Grove cemetery, though the McNeelys had no ties to that township in northern Iredell County, I searched for clues in contemporary newspapers. Mystery cleared. Green Street cemetery is Union Grove cemetery:

The Evening Mascot (Statesville), 3 April 1909.