Indiana Medical Journal, volume 21, July 1902.

Category Archives: Newspaper Articles

Will my mother know me there?

On 4 September 1945, the “Colored News-Briefs” column of The Hopewell Times, included this brief passage:

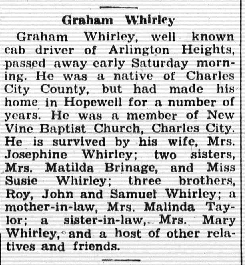

That Graham Whirley‘s death by gunshot was not reported salaciously says a lot about the regard in which he was held both inside and out of his community in Hopewell.

Three days later, the Colored News-Briefs column carried a detailed account of Graham’s funeral, held at New Vine Baptist Church in Charles City County the previous Tuesday:

“Will My Mother Know Me There?” — we’ll come back to that.

This brief piece was published 14 September. I haven’t yet found follow-up articles that reveal details of Graham Whirley and Charles Williams’ fatal encounter or of the outcome of Williams’ trial. What I have found, however, are numerous examples of the esteem in which Hopewell’s working-class African-American community held this relatively young man.

The first mention, on 8 December 1936, was a sweet one — “Miss Susie Whirley of Richmond was in the city last week visiting her brother at his home in City Point.” Though Graham’s social life — party attendance and motor excursions — received remarks (especially when he was courting a woman called Miss Carrie B. Lightly,) his singing brought the most notice. Time after time, the colored news noted that he had “rendered” a beloved hymn at a Baptist church in or around Hopewell:

- 17 September 1937, at the funeral of Sarah Washington at Harrison Grove Baptist Church, Prince George County, “I Know She Will Know Me”;

- 24 November 1943, at the service for Leroy Claiborne at Harrison Grove, an unnamed solo;

- 4 February 1944, at the homegoing of Mrs. Ada C. Jones at Mount Hope Baptist Church, “When I Reach My Heavenly Home“;

- 30 May 1944, at the funeral of Elijah Miller at First Baptist Church, Bermuda Hundred, “There’s a Bright Side Somewhere”;

- 19 January 1945, at the service for Mrs. Maria Hutchinson at Harrison Grove, Graham’s favorite, “Will My Mother Know Me There?”;

- 30 January 1945, at the service for Mrs. Lena Stith Jones at Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, “I Shall Meet My Mother There”;

- 13 April 1945, when Joe Myrick (stabbed to death by his wife) was funeralized at Union Baptist, again “There’s a Bright Side Somewhere”; and

- just two weeks later, at Robert Cottrell’s homegoing, “He’ll Know Me There.”

In the middle of this, on 22 May 1944, the column announced that “Mr. and Mrs. Graham Whirley of City Point have returned after spending their honeymoon in Baltimore, Maryland.” That, of course, was where his half-brother John Whirley and sister Matilda Whirley Brinage lived. Just sixteen months after he remarried, Graham Whirley, taxi driver and sought-after soloist, was dead. Despite his move across the James River, he had never left his home church, and he is buried at New Vine.

Aunt Ida May revisited.

Ancestry.com’s North Carolina Marriages data collection is not through demystifying my kin. A previously unknown marriage license clarified a question I had my great-great-aunt Ida’s life. If Eugene Stockton were her husband, I wondered here, why was she a Stockton in the 1910 and 1920 censuses, but referred to as his sister-in-law? In gaining an answer, I also uncovered a terrible tragedy.

Ida May Colvert‘s first marriage license was so hard to find because she married under her mother’s maiden name, as Ida May Hampton. The license lists her parents as John and Adline Colvert, but they did not marry until 1905, just over a month after Ida married Dillard Stockton on 27 December 1904. (Ida’s age is listed as 21 on the license, which is almost surely too high. Her birth year as recorded in various documents varies widely, but averages about 1885.) Dillard’s parents were listed as Henry and Frances Stockton, which seems to indicate that Dillard and Ida’s second husband Eugene shared a father and were half-brothers. (Eugene’s mother was Alice Allison [or maybe McKee] Stockton.)

Ida was a Stockton Stockton then. But what happened to her first husband, Dillard? A quick Newspapers.com search turned up the awful story:

Statesville Record & Landmark, 12 March 1907.

A little over two years after they married, Dillard Stockton and five other African-American men were crushed by a cascade of soil and scaffolding in a Statesville ditch. [Surely my grandmother knew this story?]

The stretch of Race Street in which the cave-in occurred.

For all the breathless detail of the initial report of the tragedy, greater Statesville soon moved on. As reported in the local paper, within two months, the city had settled four of the deaths with payments of $750 (roughly $19,000 today) and were close to settling with the remaining survivors, including Ida May Colvert.

Dillard Stockton is buried in Statesville’s Green Street/Union Grove cemetery. I snagged this photo from findagrave.com. I don’t recall seeing it during my recent visit and don’t know if it’s near the Colvert graves.

A horrifying post script:

Winston-Salem Union Republican, 12 May 1912.

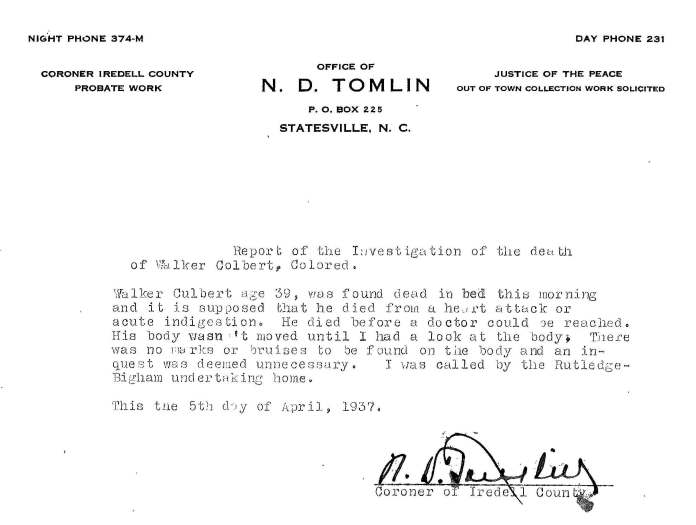

Investigation of death.

A coroner’s inquest is an official inquiry into the manner and cause of an individual’s death. Conducted by a county coroner when a cause of death is unknown, violent or otherwise suspicious, this legal inquiry is performed in public and often before a jury. The coroner does not establish why a death occurred, but rather determines who the deceased was and how, when and where death occurred. Here’s a link to a post about coroner’s reports in the North Carolina State Archives, where I obtained the documents below.

I searched Iredell County’s reports looking, in particular, for the inquest into the death of my great-grandmother’s sister, Elizabeth McNeely Kilpatrick Long, who burned to death in a suspicious fire. I was disappointed not to find one. However, I did find these for two men who died unexpected, but ultimately natural, deaths:

My grandmother’s half-brother, John Walker Colvert II. (One would expect an inquest to get the spelling of a surname right. Or at least consistently wrong.) Here’s his obituary in the 16 April 1937 edition of the Statesville Record & Landmark.

(“Schoolmate”??? Simonton Sanitary Shop? This obituary sets forth some interesting facts that I intend to explore elsewhere.)

And then there was the notorious William “Bill Bailey” Murdock, husband of my grandmother’s aunt Bertha Hart Murdock. He died just over a year after her conviction for shooting a white man in the leg in their restaurant.

No need for exodusting.

Napoleon Hagans‘ testimony before a Senate committee was not his last word on the migration of African-American farmers out of North Carolina. Nine months later, he — or someone for him, in any case, as he was unlettered — penned a letter to the editor of the local newspaper, recounting his agricultural success and exhorting his “race” to cast down their buckets where they were. His sentiments were echoed by Jonah Williams, his friend, neighbor, pastor and brother-in-law’s brother. (Jonah, too, was illiterate. Both men, however, were strong believers in the value of education and saw that their children received the best they could afford. See here, here and here.)

Goldsboro Messenger, 30 December 1880.

Adam’s diaspora: Haywood Artis.

I’ve written here and here about the migration of Adam T. Artis‘ children Gus K. and Eliza to Arkansas. Though most of his 30 or so children remained in North Carolina, a few went in North. Or, at least, a little further north. One was Haywood Artis, born about 1870 to Adam and his wife Frances Seaberry Artis. He was my great-great-grandmother Vicey‘s full brother.

Haywood Artis

In the 1880 census of Nahunta, township, Wayne County, North Carolina, Adam Artis, widowed mulatto farmer, is listed with children Eliza, Dock, George Anner, Adam, Hayward, Emma, Walter, William, and Jesse, and four month-old grandson Frank Artis. (I’ve never been able to determine whose child Frank is.]

Haywood’s whereabouts over the next 15 years are unrecorded, though he was likely still living in his father’s home most of that time. However, at some point he joined the tide of migrants flowing into Tidewater Virginia, and, on 13 January 1897, in Norfolk, Virginia, Hayward Artis, age 26, born in North Carolina to A. and F. Artis, married Hattie E. Hawthorn, 23, born in Virginia to J. and E. Hawthorn. As early as 1897, Haywood began appearing in city directories for Norfolk, Virginia. Here, for example, is Hill’s City Directory for 1898:

Haywood and Hattie and their children Bertha E., 3, and Jessie, 11 months, appeared in the 1900 census of Tanners Creek township, Norfolk County, Virginia. The family resided on Johnston Street, and Haywood worked as a porter at a jewelry store. Ten years later, they were in the same area. Haywood was working as a farm laborer, and Hattie reported four or her seven children living — Bertha, 12, Jessie, 11, Hattie, 8, and M. Willie, 2.

In the 1920 census of Monroe Ward, Norfolk, Haywood and Harriet Artis appear with children Elnora, 22, Jessie, 20, Hattie, 18, Willie Mae, 12, Haywood Jr., 8, and Charlie, 5. Haywood was a farm operator on a truck farm, daughters Elnora and Hattie were stemmers at a tobacco factory, and son Jesse was a laborer for house builders.

By 1930, the Artises were renting a house at Calvert Street. Heywood Artis headed an extended household that included wife Harriett, Haywood jr. (laborer at odd jobs), Charles, son-in-law Daniel Johnson (machinist for U.S. government) and his wife Hattie (bag maker at factory), cousins Henry Sample, Raymond G. Mickle, and Lois Sample, and granddaughters Mabel Johnson, 2, Olivia Washington, 15, and Lucille, 13, Bertha, 9, and Lois Brown, 6.

On 19 March 1955, Haywood Artis’ obituary appeared in the Norfolk Journal and Guide:

Haywood Artis, who has made his home in Norfolk for some 65 years, was buried following impressive funeral rites held at Hale’s funeral home March 7 with the Rev. W. H. Evans officiating.

Mr. Artis died March 4 at the home of his daughter, Mrs. Willie Mae Yancey, 2734 Beechmont avenue, after a long illness.

Mr. Artis, who was born in Goldsboro, NC, is survived by three daughters, Mesdames Elnora Brown, Hattie Johnson and Willie Mae Yancey, all of Norfolk, and a son, Hayward Jr., of New Jersey.

There are also 34 grandchildren, 33 great-grandchildren and other relatives and friends.

Interment was in Calvary Cemetery.

Thanks to B.G. for the copy of his great-great-grandfather Haywood Artis’ photograph.

A terrible thought ….

I ran across this article in the 19 May 1933 edition of the Statesville Landmark detailing the tragic death of a boy playing in the Green Street (then Union Grove) cemetery.

“… Five pieces of marble — two in the base, two parallel upright pieces, seven inches apart, and a horizontal top piece.”

I been all through this cemetery. There are relatively few markers there. This, however, still stands. It is the double headstone of my great-great-grandfather John W. Colvert and his wife Adeline Hampton Colvert. Though it is possible that there once were others, it is now the only one of its kind in Green Street. Was this the monument that killed Noisey Stevenson?

Roadtrip Chronicles, no. 1: Statesville cemeteries.

I made it to Statesville in good time Sunday and drove straight to the only place I really know there — South Green Street. My great-aunt, Louise Colvert Renwick, had lived there for decades, across from the street from the Green Street cemetery. As I approached her house, my eye caught a small memorial just off the curb.

Funny what you see when you’re looking. (And look closely at the plaque. Committee member Natalie Renwick is my first cousin, once removed.)

It seems odd to me that, when we were all gathered at Aunt Louise’s for the first Colvert-McNeely reunion, no one mentioned that Colverts and McNeelys were buried across the street. (Or maybe my 14 year-old self just paid no attention?) I’ve only found three graves — those of John Colvert, his wife Addie Hampton Colvert, and their daughter Selma — but there are certainly many more. Lon W. Colvert, for one. (Or was it? His death certificate indicates “Union Grove,” but why would he have been buried up there?*) And his son John W. Colvert II. And Addie McNeely Smith and Elethea McNeely Weaver and Irving McNeely Weaver, who was brought home from New Jersey for burial.

The cemetery looks like this though:

And not because it’s empty. Though closed to burials for 50 or more years, it is probably nearly full of graves either unmarked or with lost or destroyed markers. Here’s one that’s nicely marked, however, and that would I recall before 24 hours had passed:

From Green Street, I headed across town to Belmont, Statesville’s newer black cemetery. I knew Aunt Louise, her husband and son Lewis C. Renwick Sr. and Jr. were buried in Belmont, and I was looking for several McNeelys whose death certificates noted their burials here. I found Ida Mae Colvert Stockton‘s daughter Lillie Stockton Ramseur (1911-1980) and her husband Samuel S. Ramseur (1912-1989). Then Golar Colvert Bradshaw‘s husband William Bradshaw (1894-1955) and son William Colvert Bradshaw (1921-1988). (William was buried with his second wife. Golar, who died in 1937, presumably was interred at Green Street.) No McNeelys though. I expected to find both Lizzie McNeely Long and Edward McNeely, who had a double funeral in 1950, but their graves seem to be unmarked.

I was also looking for my great-grandmother, Carrie McNeely Colvert Taylor. The whole business was turning into a big disappointment. At street’s edge, I turned to head back to my car. And gasped. There, at my feet, wedged at the base of a tree:

What in the world? This is clearly not a gravesite. And, on the other side of the tree, there’s an identical stamped concrete marker for Lewis C. Renwick Sr., who died almost exactly a year after Carrie. What’s odd, though, is that he has a granite marker a couple hundred feet away in another section of the cemetery with his wife (Carrie’s daughter Louise) and oldest son. Is Grandma Carrie actually buried in the Renwicks’ family plot? Were her and Lewis Renwick’s makeshift stones pulled up to be replaced by better markers? If so, where is Grandma Carrie’s? And why were both dumped at the edge of the cemetery?

Here’s an overview of Belmont cemetery. (1) is the approximate location of Carrie M.C. Taylor’s broken marker. (2) is the approximate location of the Renwick plot.

I’ll pose those questions to Statesville’s cemetery department. If Grandma Carrie has no permanent stone, she’ll get one.

* After noticing that Irving Weaver’s obit also mentioned Union Grove cemetery, though the McNeelys had no ties to that township in northern Iredell County, I searched for clues in contemporary newspapers. Mystery cleared. Green Street cemetery is Union Grove cemetery:

The Evening Mascot (Statesville), 3 April 1909.

An educated colored man comments.

After a few observations about colored dockworkers in Norfolk and the spirit of brotherly love that enveloped black and white railroad workers, Alfred Islay Walden arrived in Wayne County. At Mount Olive, he asserted confidently that “nearly all the families own their homes and farms” and marveled at the reported wealth of “some men.” The former is not true, but the latter could have been a reference to the members of the Simmons and Wynn families, whose relative wealth dated back to their status as free skilled craftsmen and landowners in the antebellum era.

The week in Dudley is particularly interesting, as all of my paternal grandmother’s Henderson and Aldridge ancestors and relatives lived in this community in 1879, when Walden was perambulating. The “excellent school carried on by the American Missionary Society” was probably the school conducted at First Congregational Church, which my forebears founded and attended. The many who taught first and second grades in public schools included my great-great-grandfather John W. Aldridge and his brothers Matthew W. and George W. Aldridge. I’m not sure who owned the saw and shingle mills, but the landowners included the Aldridge brothers and their father Robert Aldridge, Lewis Henderson and his father James Henderson, Hillary B. Simmons’ father George W. Simmons, and other extended kin.

Goldsboro Messenger, 28 August 1879.

Dr. Ward’s empire.

Wilson Advance, 22 August 1889.

The Civil War set Dr. David G.W. Ward back, but not for long. When he died in 1887, he stood possessed of more than 1900 acres in Wilson and Greene Counties.

[As an aside, Ward’s administrator, Frederick A. Woodard, was elected Democratic Congressman to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1892. He lost his bid for re-election to George H. White, a visionary African-American who was the last black Southerner elected to Congress until the post-Civil Rights era. I attended a middle school named for Woodard.]

[As another aside — literally — I think it’s safe to say that Sarah Ward’s children received nothing from the doctor’s estate.]