As noted previously, there is no known relationship between Celia Artis and my great-great-great-grandfather Adam T. Artis, though it is likely that most free colored Artises shared a common ancestor in the misty mists of time. Like, the late 17th century. Celia’s family and Adam’s family were among several sets of Artises living in northeastern Wayne County in the antebellum era, and they intermarried and otherwise interacted regularly. Here’s what I know of Celia Artis and her descendants.

Celia Artis was born just before 1800, presumably in Wayne County. Nothing is known of her parentage or early life. She married an enslaved man named Simon and gave birth to at least six children. In 1823, she gave complete control over her oldest children to two white neighbors, brothers (or father and son) Elias and Jesse Coleman, in a dangerously worded deed that exceeded the scope of typical apprenticeship indentures: This indenture this 16th day of August 1823 between Celia Artis of the County of Wayne and state of North Carolina of the one part, and Elias and Jesse Coleman of the other part (witnesseth) that I the said Celia Artis have for an in consideration of having four of my children raised in a becoming [illegible], by these presence indenture the said four children (to viz) Eliza, Ceatha, Zilpha, and Simon Artis to the said Elias and Jesse Coleman to be their own right and property until the said four children arives at the age of twenty one years old and I do by virtue of these presents give and grant all my right and power over said children the above term of time, unto the said Elias and Jesse Coleman their heirs and assigns, until the above-named children arives to the aforementioned etc., and I do further give unto the said Elias and Jesse Coleman all power of recovering from any person or persons all my right to said children — the [illegible] of time whatsoever in whereof I the said Celia Artis have hereunto set my hand and seal the day and year above written, Celia X Artis.

Despite the “own right and property” language, Celia did not sell her children exactly, but what drove her to this extreme measure? Because she was not legally married, her children were subject to involuntary apprenticeship until age 21. This deed records her determination to guard her children from uncertain fates by placing them under the control of men she trusted, rather than those selected by the court.

Despite the deed’s verbiage, it is likely that the children continued to live with their mother during their indenture. Certainly, Celia, unlike many independent women of the era, had the wherewithal to care for them, as evidenced by her purchase of 10 acres from Spias Ward in 1833. Wayne County deeds further show purchases of 124 acres and 24 acres from W[illiam] Thompson in 1850 and 1855.

By 1840, Celia Artis was head of a household of eight free people of color in Black Creek district, Wayne County — one woman aged 36-54; three girls aged 10-23 [Eliza, Leatha, Zilpha]; one girl under 10 [unknown]; two boys aged 10-23 [Calvin and Simon]; and one boy under 10 [Thomas].

In the 1850 census, she was enumerated on the North Side of the Neuse, Wayne County, as a 50 year-old with children Eliza, 34, Zilpha, 28, Thomas, 15, and Calvin, 20, plus 6 year-old Lumiser, who was probably Eliza’s daughter. Celia is credited with owning $600 of real property (deeds for much of which went unrecorded), and the agricultural schedule for that year details her wealth:

- Celia Artis. 50 improved acres, 700 unimproved acres, value $600. Implements valued at $25. 2 horses. 1 ass or mule. 1 ox. 21 other cattle. 40 sheep. 500 swine. 500 bushels of Indian corn. 100 lbs. of rice. 2 lbs. of tobacco. 100 lbs. of wool. 100 bushels of peas and beans. 200 bushels of sweet potatoes.

She also appears in the 1850 Wayne County slave schedule, which records her (and another free woman of color Rhoda Reed’s) ownership of their husbands:

In 1860, in a surprise move, the census taker listed Simon Pig Artis, Celia’s husband, as the head of household. If he’d been freed formally, there’s no record of it. (Simon Pig’s nickname is explained here.) He is also listed as the 70 year-old owner of $800 of real property and $430 of personal property — all undoubtedly purchased by Celia. Their household included son Thomas, daughter Zilpha, and granddaughters Lumizah, 17, and Penninah, 11. On one side of the family: the widower Adam T. Artis, his three children, his sister and her child; on the other: Celia and Simon’s son Calvin, his wife Serena [maiden name Seaberry, and a cousin of Adam’s next wife Frances Seaberry], and their four children. Other neighbors included Lemuel Edmundson.

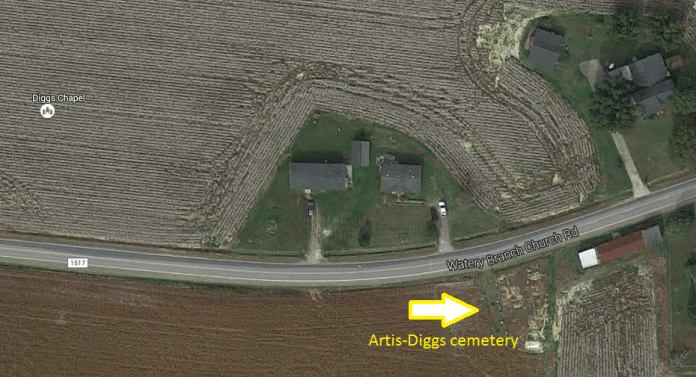

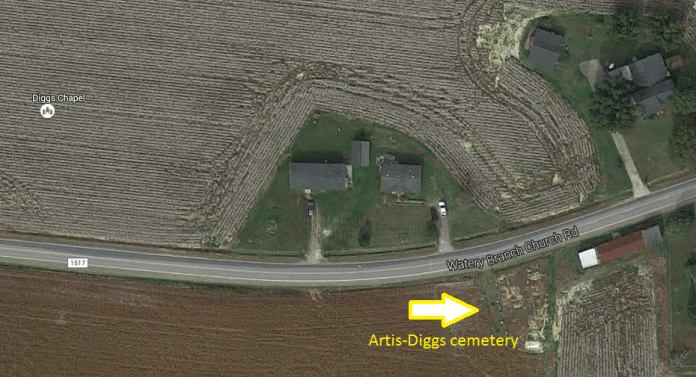

The 1863 Confederate field map below indicates “C. Artis” near Watery Branch and “L. Edmundson.” (The stars mark the creek and the towns of Stantonsburg and “Martinsville,” now Eureka.) The family’s cemetery remains on that land, as marked in the second map. (Watery Branch is perhaps a mile south along Watery Branch Road. And Diggs Chapel, presumably, is connected to the family. See Eliza Artis, below. The road visible below Celia’s name on the 1863 map was probably the precursor of Watery Branch Church Road.)

During the Civil War, both Celia Artis and her son Calvin were assessed taxes by the Confederate state government in the form of tithed crops. In December 1863, Celia had to hand over a tenth of her 2500 pounds of cured fodder to support the war effort.

Neither Celia nor Simon appears in the 1870 census. It seems likely that Celia was alive for at least a few more years, however, as her estate was not opened until 1879. It was surprisingly small, suggesting that she had distributed most her land and valuables (or otherwise lost them) before her death. Son Thomas is listed as the sole heir to her $200 estate. I don’t know what became of Simon Pig.

Here’s what I know of Celia Artis’ children:

- Eliza Artis was born circa 1816. She never married but had at least three daughters, Loumiza, Frances and Penina Artis. Descendants assert that the father of some or all of them was James Yelverton, a white farmer who lived nearby. Loumiza is known only from the 1850 and 1860 censuses. Frances was born about 1845. She never married but had at least two children, Sula and Margaret, allegedly by Wilson (or William) Diggs, whom she married in Wayne County on 15 October 1868. (Margaret’s daughters Etta and Minnie Diggs married William M. Artis and Leslie Artis, respectively, a son and grandson of Adam T. Artis. Sula’s daughter Lizzie Olivia married Leslie Artis’ brother Odell.) Penina, born about 1849, married James Newsome. Eliza’s will was filed in Wayne County:

In the Name of God Amen: I Eliza Artis of the County of Wayne and State of North Carolina being of sound mind and memory and considering the uncertainty of human life do therefore make Publish and declare this to be my last Will and testament: That is to say first after all my burial expenses are paid and discharged the residue of my estate. I give and bequeath and dispose of as follows to wit to John Newsom son of James Newsom and Penina Newsom Four Dollars to Francis Diggs all the balance of my personal and real estate that I may be in Possession of at my death during her Natural life and after the death of said Francis Diggs all of said Personal and real estate is to be equally divided between Francis Diggs’s three children Sula Artis Margrett Diggs and William Diggs Likewise I make constitute and appoint Noble Exum and George Exum to be my Executors to this my last Will and testament hereby revoking all former wills made by me In witness whereof I have hereunto subscribed my name and affixed my seal this the eleventh day of February in the year of our lord one Thousand eight hundred and Ninety Eliza X Artice {seal} In the presence of Witnesses John H. Skinner, R.H. X Locus Hand-written notation in margin: “See Book No 32 Page 320 Register of Deeds Office” [Wayne County Will Book 1, page 524]

——

- Letha Ann Artis (the “Ceatha” above) was born about 1820 and married John Artis. They lived in the Eureka area of Wayne County and their children included Sarah Artis, Zachary/Zachariah Artis, James Artis, Mildly Artis Baker (whose grandson Richard V. Baker married Lillie Odessa Artis, daughter of Henry J.B. Artis and granddaughter of Adam T. Artis), William Thomas Artis, Elizabeth Artis Brantham, and Jackson Artis. Letha Ann died circa 1896.

I Lethy Ann Artice of Nahunta Township, State of North Carolina being of sound mind and memory, do declare this to be my last will and testament. I give and bequeath to my son James Artice Five acres of land known as my fathers place to have to hold through his natural life, after his death to Maggie Artis his daughter. But should she want to live on said land before his death, I give her a right, so to do. I give and bequeath to Luby Baker and Anna Baker the children of Mildly Baker Four acres provided Mildly Baker shall be guardian for said children until they reach their majority. I give and bequeath to Bettie Bradford and Brantham Five acres land to have and to hold their natural life afterwards to their heirs. I give and bequeath to Zachary Artice Five acres land. I give and bequeath to John and Octavius the sons of Thomas Artis my son Four acres land if they should want to sell each other all right but no one else. I give and bequeath to Zachary his fathers chest. All heirs to pay Zachary Artice for burial expenses Sarah & Jackson, before coming in possession of the property I give. I also give to Zachary the big pot, I also give him his house, no matter on whose land it falls on. Be it understood I have already given Zachary ½ acre during my life time. I also gave Thomas Two Dollars and a Bull. I also give Baker a cow and calf, Betsey two Dollars I say this to show what I have given. Betsey and Mildly I give one bed a piece, my large bed to be divided between Tom & Zachary. I also give Maggie Artice James daughter, Sarahs chest. I also give the [illegible] and gear to Scintha Ann Artice. All the heirs, with Scintha Ann take my wearing clothes also House furniture also. But should Zachary want any particular thing, as he been my protector let him have it I appoint I.F. Ormond Executor of this will. In witness whereof I Letha Ann Artice have herewith set my hand and seal This 9th day of Oct 1892 Letha Ann X Artice Subscribed by the testator in the presence of each of us and declared by her to be the last will testament Witnesses J.H. Skinner, Noble Exum [Wayne County Will Book 2, page 184; proved 2 January 1897, Superior Court, Wayne County]

——

- Zilpha Artis was born in the 1820s. She never married and had no known children. She died in 1882, leaving this will:

Know all men by these presents that I Zilpha Artis of the County of Wayne and State of North Carolina being of sound mind and memory but considering the uncertainty of life do make and declare this my last will and testament in manner and form following that is to say. That my Executor Philip Fort shall provide for my body a decent burial according to the wishes of my relatives and friend and pay all funeral expenses together with my just debts to whomsoever due out of the money that may first come into his as a part or parcel of my estate. I give and devise to my niece Francis Diggs all of my entire lands and all my household and Kitchen furniture to have and to hold to her the said Francis Diggs for and during the time of her natural life and after her death to be equally divided between her two children Sula Artis and Margaret Diggs their heirs and assigns forever I give and bequeath to my Sister Eliza Artis the sum of fifty cents I give and bequeath to my Sister Leatha Artis the sum of fifty cents I give and bequeath to Brother Calvin Artis the sum of fifty cents And I give and bequeath to my brother Thomas Artis the sum of fifty cents And lastly I do hereby appoint and constitute Phillip Fort my lawful executor to all intents and purposes to execute this my last will and testament according to the true intent and meaning of the same and every part and clause therein hereby revoking and declaring utterly void all other wills and testaments by me heretofore made. In testimony whereof I the said Zilpha Artis do hereunto set my hand and seal this 19th day of November A.D. 1881 Zilpha X Artis {seal} Signed and sealed in the presence of B.J. Person, John B. Person [Wayne County Will Book 1, page 245; proved 20 September 1882, Probate Court, Wayne County]

——

- Simon Artis. I’ve found no record of Simon after his 1823 indenture to the Colemans.

——

- Calvin Artis, known as Calv Pig, was born about 1830. In 1853, he married Serena Seaberry, daughter of Theophilus and Rachel Smith Seaberry and a cousin of Adam Artis’ wife (and my great-great-great-grandmother) Frances Seaberry Artis. Their children were Martha Artis Locus, Polly Artis, James Madison Artis (who married Adam T. Artis’ oldest daughter Caroline Coley), Henry T. Artis, Nettie Artis Exum, Ellen Artis, Talitha Artis, Simon Artis, and Jeffersonia Artis. Calvin seems to have died between 1880 and 1900.

——

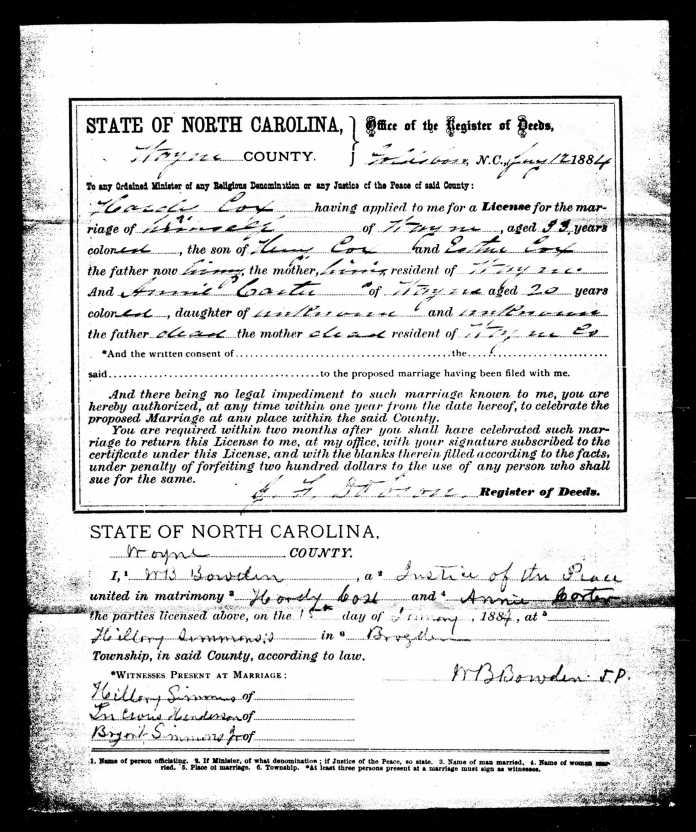

- Thomas Artis, known as Tom Pig, was born 1835. His first wife, whom he married in 1868, was Loumiza Artis, also known as Loumiza Williams, daughter of Vicey Artis and Solomon Williams. Their children were Magnolia Artis Reid, Maloy (or Lawyer) P. Artis, Larry R. Artis and Solomon Artis. Loumiza died in 1879, and Thomas married Bettie Barnes, daughter of Ben and Harriet Barnes, on 17 May 1893 in Wilson County. Shortly before his death in 1909, Tom Artis was embroiled in a lawsuit over the ownership of a small farm near Eureka. Excerpts from the testimony in that trial have been serialized in this blog, and the trial transcript makes up the bulk of Thomas’ estate file.

——

Federal population, agricultural and slave schedules;Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, 1861-1865, National Archives and Record Administration; Deeds, Register of Deeds Office, Wayne County Courthouse, Goldsboro; Will Books, Office of Clerk of Superior Court, Wayne County Courthouse, Goldsboro.

The landscape of my childhood was level. Pine trees and flatness. Devoid, I thought, of any markers of geographical history. No boulder-strewn outcroppings, no foreboding hills, no deep-cut canyons. However, to the contrary, the most obvious relic of deep time was right under my feet.

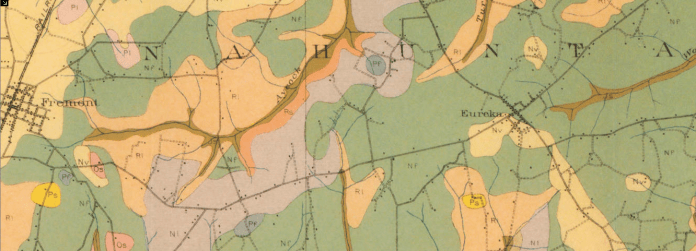

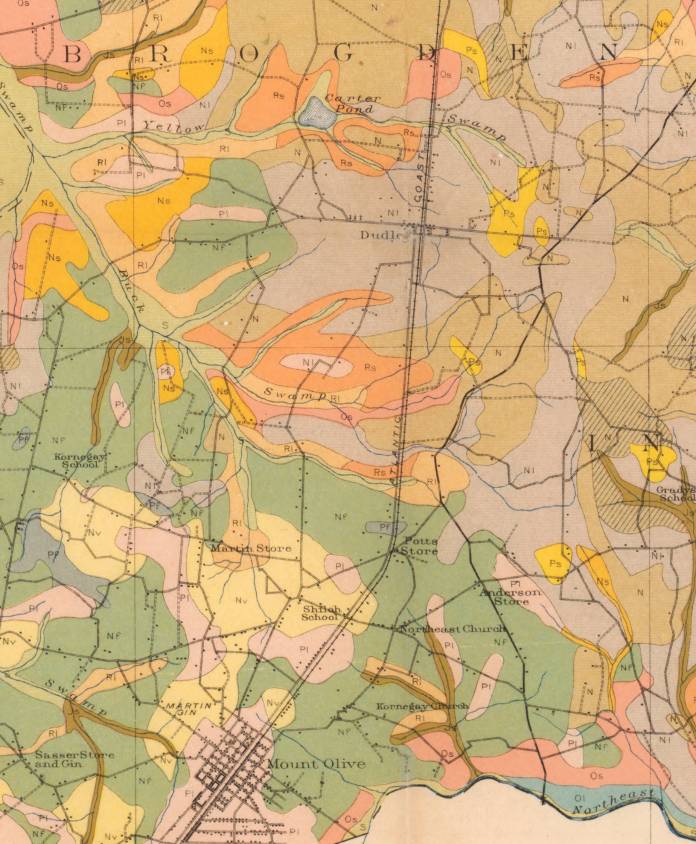

The landscape of my childhood was level. Pine trees and flatness. Devoid, I thought, of any markers of geographical history. No boulder-strewn outcroppings, no foreboding hills, no deep-cut canyons. However, to the contrary, the most obvious relic of deep time was right under my feet. Just below Eureka is a blob of Nv, “Norfolk very fine sandy loam.” The greenish Nf that dominates the frame is “Norfolk fine sandy loam.” This is Adam Artis territory. The pale lavender-gray that washes across the middle is plain “Norfolk sandy loam,” Nl. The only color left in the areas in which my family lived is the sliver of peach that hugs the south side of Aycock Swamp — Ps or “Portsmouth sandy loam.” What is all this?

Just below Eureka is a blob of Nv, “Norfolk very fine sandy loam.” The greenish Nf that dominates the frame is “Norfolk fine sandy loam.” This is Adam Artis territory. The pale lavender-gray that washes across the middle is plain “Norfolk sandy loam,” Nl. The only color left in the areas in which my family lived is the sliver of peach that hugs the south side of Aycock Swamp — Ps or “Portsmouth sandy loam.” What is all this? The Hendersons and Aldridges and their related families, Simmonses, Wynns, Manuels, and Jacobses among them, lived within a few miles’ radius of Dudley. The soils they wrestled with included Norfolk sand (N), Norfolk sandy loam (Nl), Portsmouth sandy loam (Ps), and Ruston sandy loam (Rs). The same basic dirt as in the north of the county, with the addition of the Ruston, defined here: “The Ruston series consists of very deep, well drained, moderately permeable soils that formed in loamy marine or stream deposits. These soils are low in fertility and within the root zone have moderately high levels of exchangeable aluminum that are potentially toxic to some agricultural crops but are ideal for the production of loblolly, slash, and longleaf pine. The soils have slight limitations for woodland use and management.”

The Hendersons and Aldridges and their related families, Simmonses, Wynns, Manuels, and Jacobses among them, lived within a few miles’ radius of Dudley. The soils they wrestled with included Norfolk sand (N), Norfolk sandy loam (Nl), Portsmouth sandy loam (Ps), and Ruston sandy loam (Rs). The same basic dirt as in the north of the county, with the addition of the Ruston, defined here: “The Ruston series consists of very deep, well drained, moderately permeable soils that formed in loamy marine or stream deposits. These soils are low in fertility and within the root zone have moderately high levels of exchangeable aluminum that are potentially toxic to some agricultural crops but are ideal for the production of loblolly, slash, and longleaf pine. The soils have slight limitations for woodland use and management.”