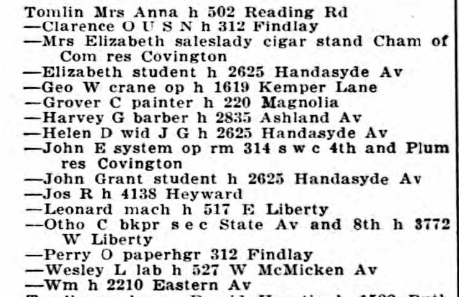

My grandmother: He had a brother that was a barber. His name was Golar, and we called him “Doc.” Papa had him in there. Papa had a chair, and Doc had the second chair, and Walker had the third chair.

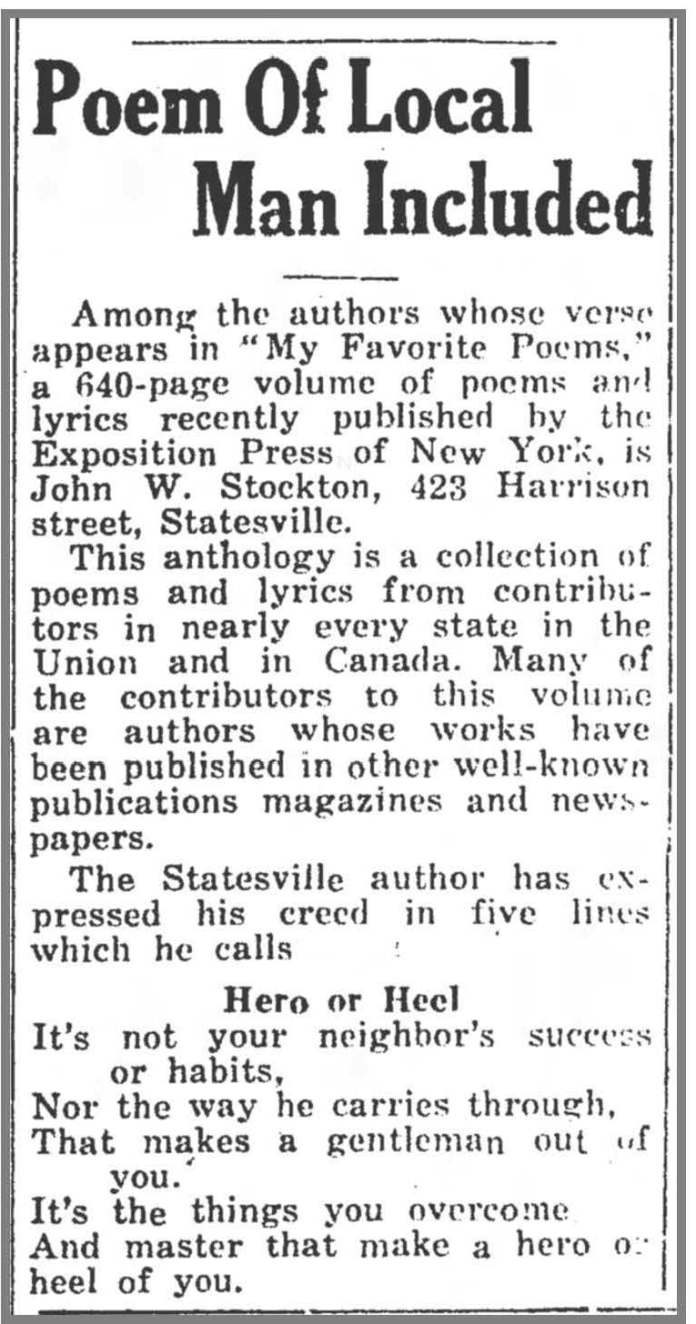

Harvey Golar Tomlin was the only one of Harriet Nicholson Tomlin Hart‘s second set of children to see the twentieth century. Harriet and Abner Tomlin had as many as six children together, but I only know the names of three — Milas, Lena and Harvey Golar.

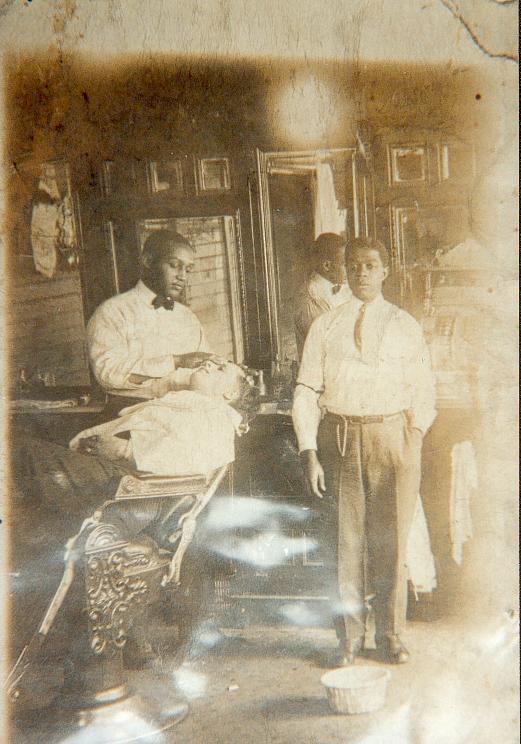

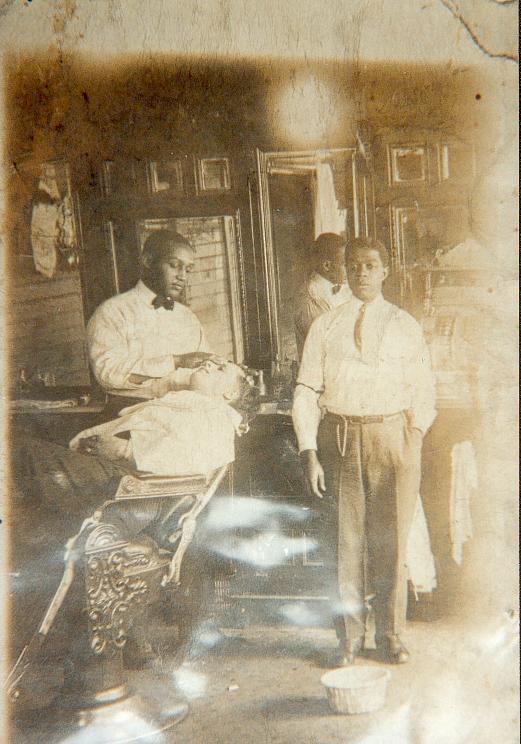

After Ab’s death about 1899, and perhaps Lena’s around that time, too, Harriet packed up her youngest son and took him to Charlotte, where they are found in the 1900 census living at 611 East Stonewall with Harriet’s half-brother William H. Nicholson. This photo may have been taken there:

They did not stay long. In 1902, Harriet gave birth to Bertha Mae Hart, whose father Alonzo she married in 1904. By 1910, Harvey Golar, called “Doc,” had left his mother and stepfather’s household and was living in the Wallacetown neighborhood of Statesville with his half-brother and family: Lon W. Colvert, a barber, wife Caroline, and children Mattie, Gola, Walker, Louise, and Margaret (my grandmother). He trained under Lon and went to work in his shop. In the photo below, which can be dated to 1917 by another taken at the same time and showing a calendar, Doc appears with Lon’s son Walker and a client.

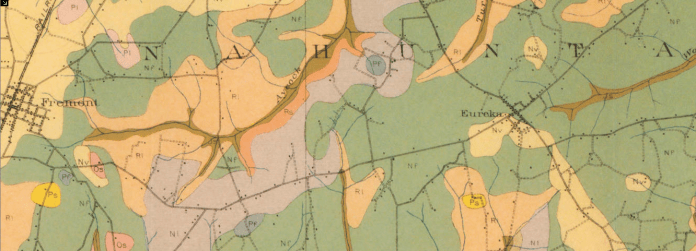

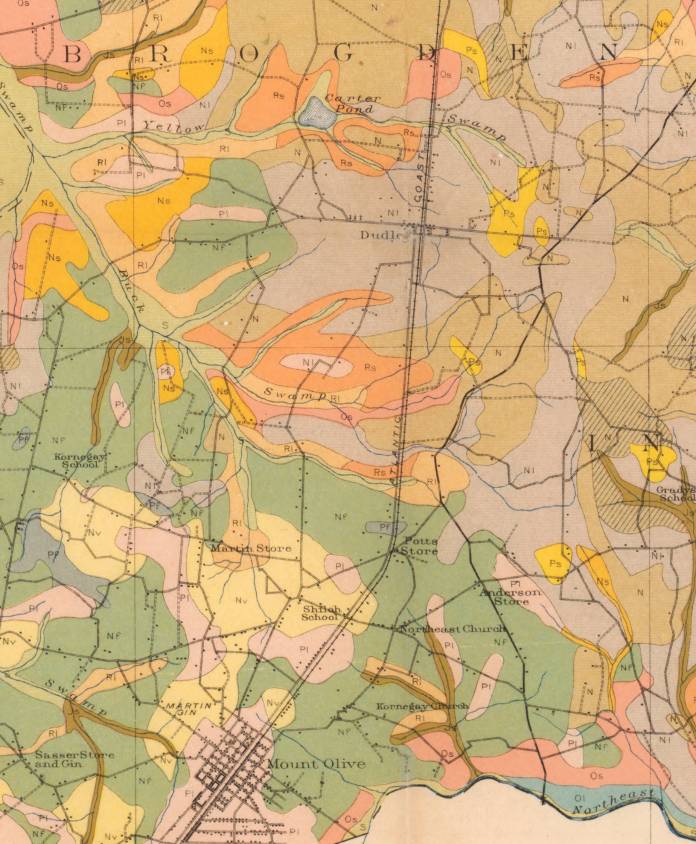

On 11 Jan 1917, H.G. Tomlin sold a parcel of land to L.W. Colvert and wife Carrie Colvert for $10. In a deed filed at Iredell County Courthouse, the land was described as “Beginning at a stake at a post oak, Ramsour’s old corner, running North 88 W. 16 1/2 poles to a stake on road East of the track of the A.T. & O. R.R.; thence S. 8 W. 9 1/2 poles to a stake Pearson’s corner; thence S. 88 E. 16 1/2 poles to a stake; thence N. 8 E. 9 1/2 poles to the beginning, containing one acre more or less and being the identical lands conveyed by William Pearson and wife to Abb. Tomlin by deed, dated 19th day of June, 1891 and recorded in deed Book No. 17 at page 101 of the Records of Deeds of Iredell County.” Doc apparently had inherited the property from his deceased father, though I’ve found no estate file.

Doc was possibly liquidating his assets as he pulled up stakes in Iredell County. Five months later, he registered for the World War I draft in Middlesboro, Bell County, Kentucky. (Middlesboro, Kentucky? What was the pull? The push?) Though he was prime age and had no infirmities, I have no evidence that he ever served in the military.

In any case, Doc seems not to have stayed gone for long. On 7 September 1918, Harvey Golar Tomlin applied for a marriage license for himself, of Iredell County, age 24, colored, son of Ab Tomlin (dead) and Hattie Hart (living), and Flossie M. Stockton of Iredell County, age 24, colored, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Stockton, both dead. L.W. Colvert witnessed the application, and W.O. Carrington, minister of the A.M.E. Zion Church, married the parties on 8 September 1918 before L.W. Colvert, N.S. Allison, and Eugene Stockton. (Flossie was the sister of Dillard and Eugene Stockton, both of whom married Lon Colvert’s half-sister Ida Mae Colvert.)

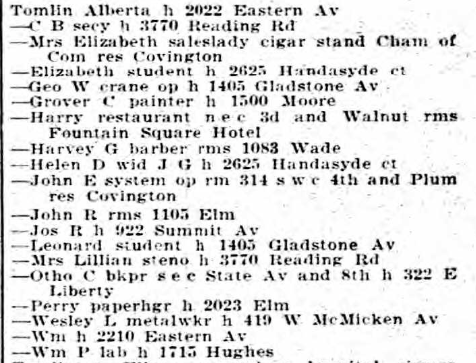

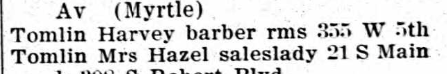

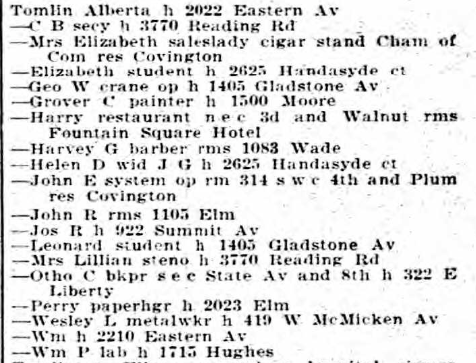

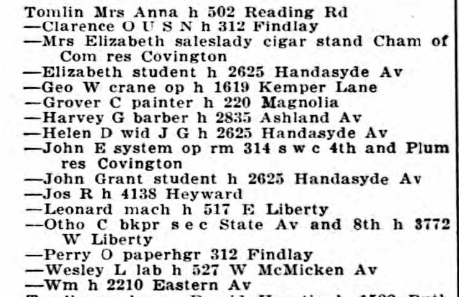

The couple’s only child, Annie Lavaughn Tomlin, was born 9 August 1919 in Statesville. At least part of that year, however, Doc was in Louisville, Kentucky, as shown in the city’s 1919 directory:

The 1920 census shows the family in the north Statesville suburbs: Jessie Stockton, age 28; his sister Flossie Tomlin, age 25, a public school teacher; niece Anna L. Tomlin, 4 month; and brother-in-law Havey Tomlin, age 26, barber. Doc’s last-place listing in the household is telling. Was he really there? Or tacked on as an afterthought because, after all, he was Flossie’s husband?

There are clues. Both Flossie and Doc were enumerated twice in the 1920 census. On Garfield Street in Statesville, public schoolteacher Flossie Tomlin and her daughter Annie L. appear in the household of Flossie’s brother Eugene Stockton, his sister-in-law (technically, but in reality his common law wife) Ida M., and their four children. The enumerator recorded this household in January 6, 1920. Seven or eight days later, however, 200 miles away in Lynch, Harlan County, Kentucky, another censustaker recorded 26 year-old North Carolina-born barber Harvie Tomlin as a roomer in the household of barbershop manager Alex R. Simpson and his wife, Lina. Then on March 3, Flossie and Annie were recorded in Jesse’s house, above. I’d bet money that Doc was actually in Kentucky.

I don’t know where Doc spent the 1920s, but it was more likely that he drifted around the Appalachian Plateau than returned to Statesville. There are glimpses.

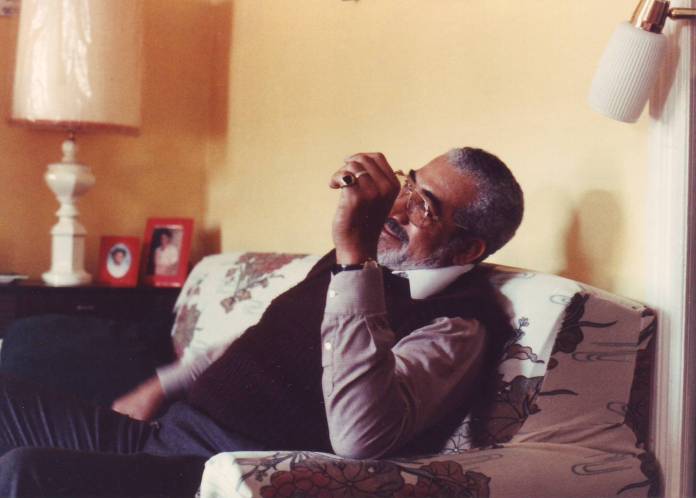

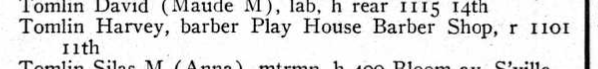

For example, in the 1925 Dayton, Ohio, city directory:

And then the 1926 Portsmouth, Ohio, city directory:

Doc did not stay long at the Play House. On 19 May 1927, the barbershop ran an ad in an announcement of the grand re-opening of the Play House building and its businesses. Harvey G. Tomlin is not among the barbers listed:

The 1930 census found barber Harvey Tomlin in Carnegie, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, living at 205 Broadway in the household of Sabry Goldsmith, a 35 year-old Florida-born barbershop proprietor. He was described as single.

Perhaps he was.

The 1932 city directory of Cincinnati, Ohio, shows Doc living in a boarding house on Wade Street:

However, on 6 July 1933, in Newport, Campbell County, Kentucky, Harvy G. Tomlin, 40, colored, divorced, born in North Carolina to Ab and Harriett Tomlin and a resident of “Cin. O.” married Lena R. Simpson, 49, colored, widowed, born in Kentucky to John and Elizabeth [no last name reported]. Thomas Hanly, J.P., performed the ceremony before Helen Peddiford and Helen Byers. The couple had applied for the license in neighboring Kenyon County, Kentucky. Lena Simpson, you may recall, was married to Doc’s employer and landlord at the time of the 1920 census.

The 1936 Cincinnati city directory shows Doc living in a house, presumably having found SROs unsuitable to married life:

In the 1940 census of Cincinnati, Hamilton township, in a rented two-family house at 943 Monastery Road, the census taker encountered Harvey G. Tomlin, 48, and Lena R. Tomlin, 58. Harvey apparently had put down his barbering tools and worked as a butler for a private family. The couple are erroneously described as white, and their birthplaces are reversed. (Harvey’s is listed as Kentucky; Lena’s, as North Carolina.)

Two years later, despite a negligible chance of being called up, Harvey Golar Tomlin registered for the World War II draft in Cincinnati.

The back of the card noted that he was 5’4″ tall and weighed 198 pounds and that he had brown eyes, black hair and dark skin.

The following year, Doc returned to Statesville to obtain a so-called delayed birth certificate. It was filed on 31 July 1943, showing that Harvey Golar Tomlin was born 12 May 1894 in Statesville, that his birth was attended by Dr. Long, and that his parents were Abb Tomlin, colored, born 1852 in Iredell County, and Harriet Nicholson, colored, born 1862 in Iredell County NC.

I lose sight of Doc for more than a decade until the Statesville Record & Landmark posted a brief article on 8 June 1955 mentioning that Bertha Hart Murdock had left half-interests in a lot to her brother “Harry” G. Tomlin and niece LaVaughn Schuyler.

Lena Tomlin died 17 July 1959 in Cincinnati. Doc did not grieve long for he was back in Statesville getting married six months later. In another small-world, keep-it-in-the-family moment, Doc’s third wife, Mary Bell Frink, was the widow of William Luther McNeely, whose sister Caroline married Doc’s brother Lon Colvert.

It was a short-lived union. On 8 May 1961, Harvey G. Tomlin, son of Abbe Tomlin and Harriet last-name-unknown, died in Statesville of coronary thrombosis. He had been living at 229 Garfield Street (Ida Colvert Stockton lived at 214 Garfield) and working as a butler.

I’ve been able to find very little about Doc’s only child. Social Security records indicate that Lavaughn Tomlin married a Scruggs in about 1943 and a Schuyler about 1953. She lived in Jamestown, New York, in the 1940s and died 30 May 1997 in Salisbury, North Carolina. An abstract of her death certificate reveals that she had worked as a registered nurse. She was my grandmother’s first cousin. Did she know her at all?

[Follow-up, 5 August 2015: I just found this snippet in which my grandmother mentions Doc being in the Midwest:

My grandmother: And he [her brother Walker Colvert] got a girl pregnant, and Papa sent him to Kentucky rather – so that he wouldn’t have to marry that girl.

Me: Really?

Grandma: Yes, he did.

Me: What did he do in Kentucky?

Grandma: He was a barber out there.

Me: Oh, okay.

Grandma: And I had, I had an uncle. Uncle – I don’t know if you’ve seen Doc or not. … Doc was out there. In Louisville. And he sent for Walker. And Papa sent him out there ….]

Interview of Margaret C. Allen by Lisa Y. Henderson; all rights reserved.